5. Audition

Japanese Horror has always been at the pinnacle of horror filmmaking, scaring the world time and time again with their masterful pacing and unnerving atmosphere. Films like Ringu and Grudge redefined the entire horror scene for good, but the one that truly made heads turn would be Takeshi Miike’s Audition.

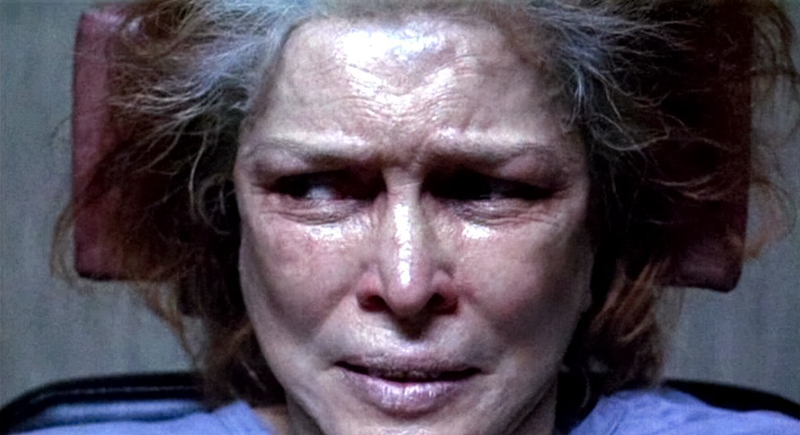

An undeniable, key and quintessential aspect of this class of horror films are ghosts and jumpscares. This is their unique gimmick, the one that Western Cinema can only dream of replicating. Audition is a film that for the most part, did away with both. It tells an unassuming story of a widower on a journey to find true love, resorting to holding auditions to find “the one”. Unfortunately for him, his “one” turned out to be a psychopath.

Audition is a film that speaks wonders for the message of feminism and female empowerment, beneath the surface of the insane horror that it is, it actually provokes some insightful thought, through its unique presentation as well as the complex and subversive characters it brings to life. Unfortunately, this is also a film that makes you afraid of going to dates, it makes you afraid of even speaking to a woman

. It has a slow start, for sure, but midway through the film, it really kicks off and changes course in the most jarring of ways, a literal 180 in the story so much that we literally go from bored to intrigued to completely fearing for our own lives.

Asami and the term “Kiri-Kiri-Kiri” have truly burned their ways into horror film history.

4. Whiplash

Who would’ve ever thought that a film about jazz musicians would be one of the tensest cinematic experiences of all time? Whiplash is a film that for the most part, came out of nowhere before going everywhere, it cemented JK Simmons’ portrayal of Fletcher as one of film’s most iconic, as well as Damien Chazelle as an unbelievably talented filmmaker.

The film takes your typical rags-to-riches tale and cranks it to the maximum. It tells a story of a young drummer, Andrew Neiman, on a journey to greatness “guided” by an unrelenting band instructor, pushing him to the absolute limit. The anxiety in this film comes mostly from JK Simmons’ ferocious performance as Fletcher, the band instructor. He commands so much power and just screams dominance. His glare alone can strike fear into the hearts of audiences worldwide. Unfortunately, he does so much more than glare. He explodes both physically and verbally onto the hapless bandmates, he is the very personification of the idea of rage. And we’re on the receiving end of it.

This crazy intensity is matched with an even crazier passion from Andrew. JK Simmons might have stolen the show but Miles Teller certainly touched our hearts. Anyone in his position in their right minds would have left, they wouldn’t stand for the abuse. He did. Watching that unstoppable force pitted against that unmovable object is certainly an experience, to say the least, making us forget that at the end of the day, this is a movie about jazz music, of all things.

The final scene is certainly up there as one of the greatest endings to film of all time. A culmination of everything the film builds up to, the intensity from the two leads, Chazelle’s direction. Everything. It’s no wonder that Whiplash is a film with overwhelming critical response, winning 3 Oscars and earning an 8.5 on iMDB. It’s a film that, even if you don’t enjoy, leaves you physically and emotionally floored.

3. Misery

Kathy Bates delivers undoubtedly one of the best performances of not only her career but in cinema with her role as Annie in Misery. Where JK Simmons conveyed anxiety through theatrical monstrosity, Kathy Bates did through a far more restrained one, one that could erupt in any second.

The story, though a simplistic home thriller at its core is essentially exemplified by the psychotic nature of Bates’ characters, with her performance brilliantly dipping in and out from fan to fanatic, with Reiner managing to capture the sheer energy channeling from her performance. Though cinema has seen greater horror films which loosely follows the same narrative structure as Misery, and it isn’t exactly what one would deem original, everything just feels so real, despite all the madness.

Films like Halloween and Friday the 13th dealt with undead monsters, individuals you know do not exist in our physical world. No matter how creatively they stalk and kill their victims, you know beyond a shadow of a doubt that they do not exist in our world. What about Misery? We’ve all had run-ins with an Annie-type in our lives, an obsessive stalker, a deranged fan, with the advent of social media, these characters become all the more apparent, albeit at a much less exaggerated scale than Annie, but on the same scale nonetheless.

Perhaps the most unsettling aspect of the film is that Annie is able to thrive as a functioning member of society on the outward, but behind closed doors, there is a monster living in a human’s body.

2. Requiem for a Dream

In this singular experience exploring the treacherous world of drugs, Requiem for a Dream takes the idea of the montage popularized by Soviet Film Theorists in the 20s and reinvents it in a way only a true master of his craft could.

Darren Aronofsky, whether you enjoy his work or not, has always been a filmmaker unafraid to question the boundaries of the medium to deliver evocative pieces of work that seemingly transcend conventional rules of logic. His magnum opus, Requiem for a Dream, and also perhaps his most popular work, is one that delves deep into the concept of drugs and how they gravely affect the individuals who abuse them.

The film follows the intertwining lives of multiple individuals, all with relatable, realistic goals for their futures, but one way or another, these goals are cut short by their encounters with narcotics, sending them down a bottomless pit where matters only get worse and worse. The film’s anxiety stems from Aronofsky’s unique visual style, one that truly encapsulates the horrors of a world ridden with drugs and none of the glamour, one so incredibly stylized with so much unique usage of cinematography, editing and music yet still manages to stay true to what it is and deliver an experience that isn’t awe-inspiring, but excruciating.

It’s an experience that would undeniably defeat you, it would crush you seeing the complex characters you grow to care about struggle in an almost Sisyphean cycle, a cycle so horrifically depicted on screen with such raw intensity that you forget. You forget you’re in the comforts of your home. You forget you’re a healthy, functioning human being, because in that mere 1h 45min of high-octane adrenaline, you are a drug addict that lost everything.

1. Come and See

The inherent problem faced by almost every war film whatsoever is the presentation of the fundamental anti-war message. No matter how gritty or visceral the depiction of battle is, in a pursuit of producing a film that’s objectively good, such sequences, stripped down its fundamentals, are nothing more than grandiose spectacles, ironically disputing the very fabric of an anti-war message. Even the gold standard that is Saving Private Ryan’s Omaha Beach sequence is partially guilty of this fact. Come and See is perhaps the only war film in existence that manages to circumvent this intrinsic plight.

The brilliance of this relatively obscure gem of world cinema comes from the plot’s innate simplicity. Where other films of the genre feature monumental plots to complement their scale, Come and See delivers a modest humanistic character study of a young boy with misguided fantasies of warfare slowly experience firsthand the atrocities as a hapless victim rather than a harbinger of destruction.

The perspective built in Come and See from an artistic standpoint is perhaps the most innovative and poignant in the history of film. Unparalleled even up until today. The cinematography is claustrophobic, with the filmmakers opting for an extensive use of centrally framed close-ups, despite the grandiose nature of battle. What’s particularly unique is the extremely subtle yet disturbingly jarring, robotic tracking in the close-up shots.

Think of Requiem of A Dream’s agonising use of snorricam without any movement whatsoever. This is the visual style adopted in Come and See. The overall experience, combined with the extensive use of eyeline matches locks viewers into the subjective psyche of Florya, the protagonist, making for an increasingly unflinching and painful experience. Combined with the film’s highly experimental use of sound design, capturing the whole cacophonous atmosphere of war.

Never before has a shellshock on screen feel so real and uncomfortable. The two aspects when put together builds an undeniably incredible perspective, making us audiences feel the exact emotions of Florya at any given moment, the fear, the anguish, the pain, the anger. Everything. The bog sequence is genuinely one of the most horrific scenes ever put to screen.

Ironically, though this film aimed to tell a personal story, it ultimately ends up being an epic experience, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, considering the fact it did everything it set out to achieve and so much more. It’s just so powerful and painful, if anything, that this not something you can pick up and rewatch as and when you like to.

It’s an amazing, layered experience that captures war unlike any other film has ever did or probably will ever do, offering an immense range in its cinematography, with surreal poetic imagery and disorientating closeups and an overall immersive, sensorial ordeal filled with so much physical discomfort and pure anxiety.