5. The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972)

Rainer Werner Fassbinder, apart from channelizing his own determinant experiences of a lifetime in his significative cinematic portals, has delved into the female mental riddle. In Veronica Voss’s and Maria Braun’s inner turmoil we can sense some of Fassbinder demons and a true woman’s aspect at the same time. But in Petra von Kant’s torn-apart intellect he has provided space for every female role, always in a confined sphere of misery.

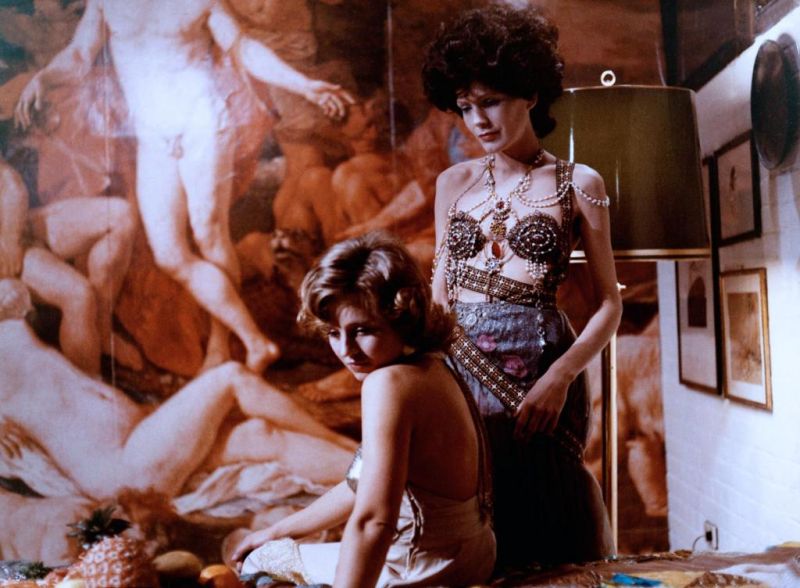

A highly stylized apartment hosts the entire film, echoing Petra’s enduring lament. She is an upper-class fashion designer who has focused on her collaboration with female models, after the end of her marriage. Meeting Karin, an almost child-like beauty that aspires to be a model, Petra is confronted with the severe feeling of rejection and unsatisfied desire. The following single camera shots of the great German director deal with his heroine’s esoteric battles and contradictions.

It’s not easy to feel sympathy for Petra. Her personality is quite unpleasant, as she vividly resembles detestable historical characters and norms. Fassbinder fearlessly illustrates a tangle of emotional pathologies on her portrait, clearly commenting on the imbalance that feeds a social divide. However, except for the political ideas which Petra represents, she also reflects on the most torturing aspect of a teenager, a lover, a wife, and even a mother.

4. Three Colors: White (1994)

The second film of Krzysztof Kieslowski’s highly acknowledged “Three Colors” trilogy tells the story of Karol, an insignificant, poor and sexually numbed Polish immigrant that was brutally sent away by his wife. Returning to his snow-capped hometown in Poland, he manages to create a small fortune, recover his equality toward his merciless ex-wife and finally take a painful revenge.

Perhaps some parameters of the plot correspond to the cynical tone of a black comedy. The film’s end, though, is deeply dramatic for both of the clashing forces. Karol’s forlorn figure can’t leave you apathetic, as he more and more sinks in the dark waters of poverty and loneliness.

Even when he strives to conquer a better fate in Poland, his pale eyes still emit a sense of misery. But at the time that he distantly observes the woman that he loved standing behind bars like a bird in the cage, Karol appears to be lonelier than ever.

Dominique, the film’s seemingly unsentimental and revengeful female figure fails to be likeable from the audience’s point of view. Her actions are led by a strong egoistic instinct. Yet, the behavioral trend that she represents is essentially explainable and down-to-earth.

Of course, Karol’s sexual incapability originates from his many and deep insecurities. On the other side, Dominique refuses to face and embrace her husband’s problems. When Karol recovers his strengths, Dominique finds the male severity that she sought. At this point her weak heart is trapped.

3. Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels (1975)

A careful observation, if one is willing to process and decompose a substantive spectacle, has the power of an experience. In this trend, Chantal Akerman’s minimalist sighting in the life of a typical housewife is defined by a raw documentarian exposition. “Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels,” in its simplistic plenitude and visual austerity, concerns an existential recording.

In her silent cage, Jeanne Dielman represents the well-combed, plastic-like stereotype of a woman that lived during the 50s. Her daily tasks involve nothing more than domestic duties. As if trapped in an eternal carnal framing, she gloomily carries her restless body around the house, aimlessly fixes her hair and looks at her face in a mirror. Yet, the tortured oddment of her deprived intellect resurfaces there, in the emptiness of her life.

Not often an extensive realistic silence delivers such a great baggage of misery and futility as this resonant protestation of a movie. Its dominant setting and methodic camerawork contribute to a prompt emotional effect. Arguably, the picture’s ponderous cinematic hours provide a challenging experience, as regards an active cerebral involvement from the viewer’s part. But once you’ve dived in, Jeanne’s vision is more than devastating.

2. The Headless Woman (2008)

You can’t deny it: Lucrecia Martel’s “The Headless Woman” is an obscure meandering of fractured thoughts in a twisted conscious chamber. Found in a suspended territory that has nothing to do with reality or mere fantasy, the disoriented kinesiology of the story’s heroine cartographies an inner storm of fears and memories. One may never understand Martel’s brainless Vero. Yet, her creator studies, understands and deeply accepts her insanity.

The plot follows the progressive mental degeneration of a middle-class woman from the moment she hits an unidentifiable object with her car. Although she does nothing at the moment of the accident, her subsequent behavior appears to be more and more out of balance, as if this sudden strike created a soundless flick in her head. Holding on that temporal verge, Martel burrows a rough road toward Vero’s shelter of memory.

“The Headless Woman” is a determined move that evolves alongside with the chaotic swirling of a woman’s struggling presence in a both palpable and comprehensible environment. Vero’s psychological break-down occurs while she attempts an impartial evaluation of her society and her place in it. Such a procedure, intelligently and cryptically portrayed by Martel, puts her at odds with her mistakes, guilt and regrets.

1. Volver (2006)

Luis Buñuel has studied the female psychology and its quintessence remains an enigma to him, as it seems. The mysteriously charming female figures of his “Belle de Jour” and “That Obscure Object of Desire” prove this theory. For Pedro Almodóvar, on the other hand, a woman has always been a transparent sacred creature that can ease every pain. Undeniably, if there’s a male film director who has honored the female presence through his work, that’s him.

The setting of his 2006 “Volver” refers to a provincial Spanish town, focusing on its representative female figures. Raimunda, adorably embodied by Penélope Cruz, is the main long-suffering heroine of this surreal film that glorifies its mundane ingredients in an uncanny cinematic way. As the toil of Raimunda’s past is revealed on a frantic unwinding of secrets, we observe her suffering, loving, and forgiving her past until the conquest of an honest esoteric catharsis.

Once again, Almodóvar has placed his profound characters at a center of a twisting story that, apart from keeping the viewer constantly attached to its curves, describes very personal treasures of his life and memory. Here, we see the multifaceted profile of a woman in her wholeness: a mother, a daughter, a victim, and a savior. Even if you don’t love his colorful extravaganza, you can’t ignore the deep beauty of the women that he sculpted in the sentimental temple of “Volver.”