6. Mon Oncle (1958)

Jacques Tati was visual comedic genius working up into the 1970s and wasn’t attempted to alter his vision in favor of sound. Of course, his films contain sound but in the smallest detail as he paints his world all through the visual aesthetics of film.

Tati’s characters do not talk as does hear as he revisits his Monsieur Hulot character. What follows is a film filled with motifs on modern architecture, technology, and materialistic way of living. All this is of course foreign to the awkward Hulot that results in downright comedy.

Tati was never a filmmaker that allow for a punchline or sudden outburst of laugh but a series of small laughs into bigger ones as he allows a scene to play out. Take the water fountains outside of his relatives house, they rise when he passes. Instead of walking passed as the audiences sees this, his Hulot goes back and forth, looping around them progressing the scene into a repetition of his off kilter comedy and further enhancing his themes.

Tati always had something to say such as Chaplin but he did it his way with the use of minimal sound effects and even the characters often whispering to one another to not distract from the physical comedy in his world. And in the case of ‘Mon Oncle’, Tati’s first color film doesn’t derail from his filmography and use of techniques.

7. The Wages of Fear (1953)

Though a bit talky in the first hour of the film it is not difficult to comprehend what is going on. Shady characters, down on their luck, wanted to make a quick buck and will do anything for it. This leads to a reversal fo chase films in Henri George Clouzot’s masterful thriller.

The premise is about four desperate men must drive nitroglycerine through mountainous roads in order to get paid. What the result is montages and extended scenes where the actors such as Yves Montand sweat their life out going five miles per hour in order not to die. Clouzot simply has the camera linger on the trucks, the men’s face, the speedometer, and the barrels of nitro and we get what Hitchcock could envy.

The film is filled with tension and suspense from opening frame to closing. However, as the film progresses, the soundscape gets quieter and quieter emphasizing you don’t even need the sound on to understand what Clouzot is doing here.

The second half of the film of the men is truly a white knuckling experience all the way to murky oily death of some of the characters. It becomes a nightmare of visuals because the men can’t even speak or what to or even more because it will lead to their demise. Either from the barrels that could go boom at any moment or the looks from their fellow greedy passengers. Cluozt allows the actors to operate in their difficult environment and use montage to convoy his themes of greed, survival, and desperation.

8. The Naked Island (1960)

As Kaneto Shindo’s film unfold before us, we start to see the rhythm of life of a family on a tiny island. We don’t actually realize that no words are being spoken because the actors are constantly moving and performing an action. We then start to realize that this film could essentially be silent, which is essentially is.

We hear the waves, the footsteps going up the mountains, the buckets of water, in which Shindo actually made his actors, regulars Nobuko Otowa and Taiji Tonoyama, do but this film is about a family where many things can unsaid.

The film continues and never ceases to be dull to one breath taking image after another on this ‘naked island’. As the film and family progresses into tragedy, no words or outbursts are filmed. Its the body language, frames of isolation filled with despair and hopelessness, and uncertainty that show Shindo’s strength as a filmmaker.

Shindo has made films where sound is crucial to the imagery but with this film, he stripped it all bare and relied on the actual imagery. And what results is a film that is essential silent but with the power of nature and humanity all around it.

9. Hero (2002)

A film by visionary Zhang Yimou that relies of wuxia action and colors for emotion. No words are spoken in the fight sequences and even the occasional footsteps across the diverse landscapes or clanks from sword or stick fighting do not hinder the visuals of this film.

Each frame of the film could be a painting, too weak for words to describe. But the power of Yimou’s film is not just amazing cinematography by the one and only Christopher Doyle but that each character’s motivation and purpose can be seen on Jet Li, Tony Leung, Maggie Cheung, Chen Daoming, Zhang Ziyi, and Donnie Yen’s faces, yes some of Hong Kong and China’s greatest actors in one film.

All of the actors convey their emotions whether still or mid-flight on a kick. One must truly surrender to beauty and violence of this film. For example, take any fight sequence and mute the sound, you are still getting what Yimou evokes from you. He doesn’t ignore sound but relies on the colors, costume, production design, actors, cinematography, and choreography to say his mind.

Yimou has never shied away from putting the visual first as apposed to acting or use of sound, but with ‘Hero’, the former is far more reliant on his vision than the latter, and it succeeds beautifully.

10. Kwaidan (1965)

Where to even begin with Masaki Kobayashi’s anthology horror, fable, ghost film that has one painterly imagine after another. This film contains four independent stories in a combination of kabuki and Not theater with cinematic technique make this film truly stand out.

How can a film containing one of not only Japan’s greatest composers but cinema’s greatest composers, Toru Takemitsu, work without sound? Well, somehow through Kobayashi’s vision and Yoshio Miyajima’s cinematography, the film strives. It plays out like a true nightmare that you simply can’t shake. From a color palette as vast of the sky and scenes that play out in slow motion that unsettle you for days after viewing it, it can work without sound, even if it is without a score from Takemitsu.

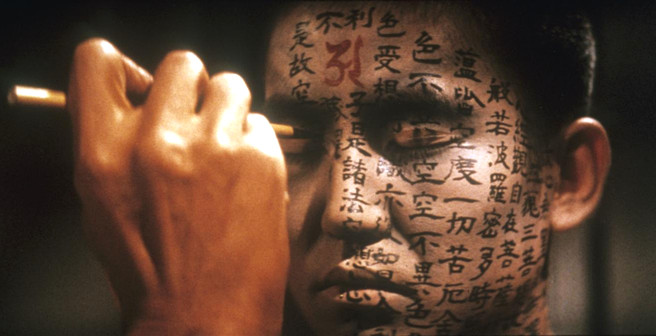

One of the most recognizable images is the painting of Japanese cartography on the face of an individual. No sound, dialogue, or score is needed to appreciate the beauty, sorrow, violence, horror, and pity that is being conveyed through this one frame. And in a film of 183 minutes of outer worldly imagery, presented in the form of a nightmare, its hard to shake from a cinephile’s mind.

Kobayashi never withdrew from controversial subject matters or violence or his incredible use of sound through swordplay, world wars, or city life, but here, the imagery alone, makes case for a great filmmaker and film that works with the sound completely off.