As if sculpting a formless body of thoughts into a palpable conformation of visions, a film director projects a textured intellectual surface on a motion picture’s transparent kinesiology. Standing across, at the viewer’s position, you drift in the film’s conceptional background, usually ignoring the constantly observing eyes and controlling hands of the recording medium.

Camerawork, in its flexible and diverse function, constitutes the vehicle that delivers a filmmaker’s story in the same prompt way that language expresses the cerebrations of a writer. From a static, carefully portrayed close-up to an unprocessed long take, and from the geometric harmony of Mise-en-scène to the dazzling effect of hand-held shooting, the camera movement comments upon emotion, intention, body, expression, rhythm, depth, script prospect, e.t.c..

The 10 following movies confirm that the detail makes the difference, standing out for their first-rate visual language. Watching them carefully, you’ll notice a remarkable technical skill that engagingly serves the creator’s imaging purposes. Let’s dare a submersion into their thick, moving optical object.

10. Chungking Express (1994)

Sometimes, silence succeeds in revealing the context that words fail to describe. In the case of Kar-Wai Wong’s cinematic universe, a totality of narrative and cinematography techniques renders the hardcore of sentiments and conditions in a visually stunning, often melodically silent and fuddling motion of ideas and images.

The flutter over a crowded yet lonely world that it is “Chungking Express” emerges under a recognizable low-key lighting, tenderly observing Wong’s gloomy, highly stylized and essentially alienated characters. If you install a part of yourself in the picture’s hospitable environments, it becomes impossible to ignore the humble and at once otherworldly beauty of the projected solitary souls, as they stroll in a maze of rowdy light and blaring darkness.

One of cinema’s greatest achievements pertains to the depiction of a story’s quintessential moods and subtexts through the use of image and sound instead of dialogue. In this piece, the great Chinese director gloriously fulfills this task, constructing a visual tale that captures the audience in its unconventional movement and bending of time. More analytically:

The shaky kinesiology of the hand-held camera creates a both realistic and intoxicating result. Wong’s distinctive “step printing” technique deforms the length of minutes in a simultaneous decelerating and accelerating pace that highlights the relativity of time.

Slow motion devices are used in order to create an artifice of stillness in the foreground or background, contributing to a kinetic antithesis which reveals the hero’s esoteric isolation. Finally, “Dutch angle” shots generate a visual effect that portrays the reflective relationship between reality and spirituality.

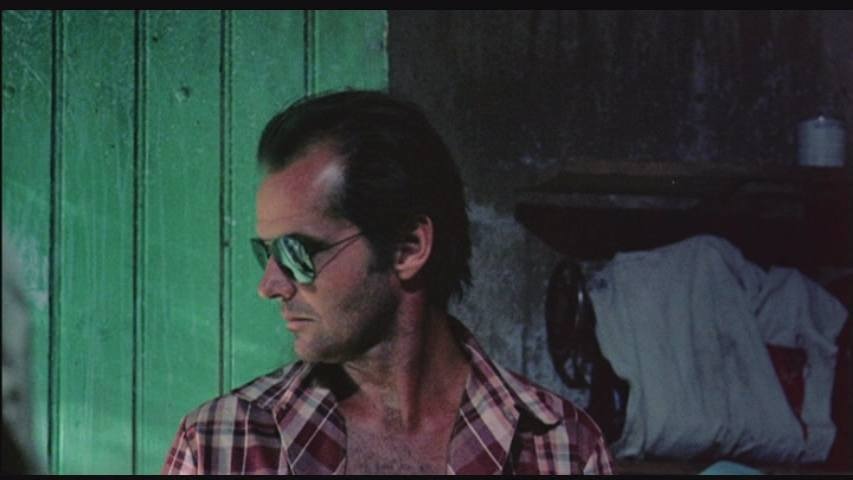

9. Deliverance (1972)

John Boorman’s 1972 adventure film “Deliverance” follows the canoe trip of four city men alongside the wild valley of Cahulawassee River which lies somewhere in Northern Georgia.

As this trip develops into a reckless step between life and death, the story attempts to expose a rough aspect of the relationship between human and nature, as well as between human and human. Brilliantly composed and glorified by a methodic camerawork, the cinematography narrates the script’s essence in visual terms.

A dogmatic contradiction between the primal serenity of Mother Nature and the hasty humane clutter is underlined by the interchanges of long takes, which record an eternal naturalistic balance, with abrupt camera movements that express intense violent feelings.

In combinatorial frames, we can also see a differentiation of the kinetic state between environments and men. This shooting technique, in its artistic beauty and poetic ambience, suggests a dominant force and an occupied army in a sequence of clash, conquest and destruction.

Very often, the excessive cinematic violence satisfies nothing more than the inherent humane need of suffering. In the ethically savage landscape of “Deliverance” the occurring violence is rooted in a decayed substrate of principle and thus, its substantial ugliness is the prominent ingredient that makes it unbearable. Transparently appearing in the foreground of the film’s visual beauty, this ugliness is willingly emphasizes by a superb technical operation.

8. Victoria (2015)

Debated and divisive, the recent German thriller “Victoria” is shot in one single take. The young female protagonist inspires the film’s title, although the story involves just a few hours of her life. As if lurking on the diary of a conscious camera, the picture describes Victoria’s portrait in 2 haunting cinematic hours.

It starts in an underground club in Berlin, where Victoria meets a gang of cheeky outlaws. Chasing a constant flow of space and time, from this point the recording medium keeps track of Victoria’s every step, quandary, choice, and intersection. From night to dawn, significant pieces of her past appear on a way full of emotion, gumption and regret. Throughout this vicious circle, the viewer effortlessly participates in the moral and sentimental ordeal of “Victoria.”

Sebastian Schipper’s overbold endeavor to capture his film in the sequence of one take unexpectedly works out really well, as his camera adopts the natural and internal movements of the protagonist character. When Victoria stands in front of a demanding decision, the picture does the same.

When she moves forward, the picture does the same, as well. Yet, when she experiences a moment of emotional balance, the camera creeps out and honors the monument with a steady observation.

7. Satantango (1994)

Béla Tarr. The king of artistic visual syntheses. The master of philosophical interpretations. Tarr’s cinema, idealistically and technically speaking, is a significant chapter of filmmaking on its own. Studying the artwork of the greatest Hungarian director, one can take substantial lessons in relation to the contextual and cinematographic construction of left-bank motion pictures.

His 1994 cosmic symphony of “Satantango” is defined by a distinctive directing structure. As the title suggests, the picture’s movement in space-time develops according to the tango’s code, attempting six steps forwards and six steps backward in time. Charting a both alive and post-mortem choreography on humanity’s map, the film’s cinematographic device victoriously succeeds in imparting its creator’s lingering ideas.

The feckless existence of a decadent farmers’ community is observed by a staring, detached camera that espies their days through a sequence of long takes and dolly shots. Tarr’s reinvention of time, as it occurs in the patiently slow observation of the setting, attributes an amaranthine and universal texture to his work. “Satantango” arguably requires a wearing cerebral involvement, but once you’ve divided in, your mind moves into the clear sphere of philosophy.

6. The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928)

Almost exclusively narrated through close-ups, “The Passion of Joan of Arc” is one of the most static films ever made. Since stagnation is still a form of movement, according to the natural norms, this silent yet emotionally howling cinematic creation is an instructional piece of how a face’s detailed portrait could describe a mind and soul in their entire depth.

Joan of Arc is introduced to the audience as a martyr. We get prepared for her inevitable conviction since the beginning, without being aware of any fact related to her past. Expositional scenes and dialogues are kept to the minimum, and thus, the film’s gravity center is rendered on Joan’s expressions that reflect on an isolated esoteric procedure. In this trend, the projected sentimental torment appears to be detached from Joan’s surrounding world, despite its external ground.

Carl Theodor Dreyer’s innovative masterpiece comprises a personalized psychological study. Its static yet powerful visual construction, which consistently steers clear from establishing takes, spatial depth and fluid movement, highlights a spiritual drifting in a cerebral islet of both painful and cathartic introspections. On its gloriously painted canvas of ideas and emotions, Maria Falconetti’s eyes glare eternally in their hedonic mental pain.