There is something appealing about “The Master of Disguise”. Yes, most of the jokes are painfully juvenile, the script is ludicrous and the cinematography is uncomfortably frenetic. Yet every now and then, in order to escape our stresses, we may just have to sit down and watch Dana Carvey play the stupidest turtle man in existence for 81 minutes. It’s a strange, primal urge humanity has yet to evolve out of like eating at Panda Express.

The following list contains the necessary medication to movies like “The Master of Disguise.” These movies’ intricate themes and direction can often compel the audience to put in mental and even spiritual work to fully appreciate them, though never in a manner that is trying. We evolve watching these movies, learn new perspectives and means to understand ourselves, the world, maybe even the universe.

In time, will we get to a point where “The Master of Disguise” will be considered to be on such a pedestal? Well given that the film has a scene where George H.W Bush saves Italy through the power of farts it may be closer than we expect. Until then we have these beacons of erudite delicacies to keep our minds satisfied.

10. Memories of Murder (2002)

“Memories of Murder” can be seen by some as a documentation of the failure of law enforcement to deal with unnatural evil. Others may view it in the lens of the frustration and fear of letting boorish and incompetent police deal with a serious threat to the community.

No matter the interpretation, “Memories of Murder” expertly fills every shot with enough details and storytelling subtleties to allow the audience to have a mental conversation with the piece. Nothing is spoon-fed and no character can be narrowed into comfortable archetypes, thus better allowing the audience to be thoroughly immersed into a cinematic world as messy and strange as our own.

This film’s cinematography/direction expertly understands an audience’s curiosity and thirst for organic human interaction. Most shots are wide angled, with the camera and acting ensemble used to create a sense of dynamism that can be at once hilarious, terrifying or heart-breaking given the situation. This direction accentuates the nuances of the script and performances, a lesson in how moviemaking ought to be about creating a lived-in sense of place with characters that are constantly shifting

“Memories of Murder’s” story of the most successful serial killer in South Korea’s history is haunting and riveting because it trusts its audience to immerse themselves in an environment already in motion. There are no Black or White hats, no clear sense of justice, just people mucking things up and a society that has to pick up after them.

9. Le Bonheur (1965)

Human selfishness has never been so cute. Agnes Varda’s piece on a man believing his own happiness will correlate with his family’s is a powerful dive into the euphoria of arrogance.

On the surface, “Le Bonheur” is almost Disney-like with its bright colors, upbeat Mozart music, and perpetually sugary tone as our hero Francois saturates his wife and children with love. Yet this idyllic sense of being makes Francois greedy and he starts cheating on his wife with a gorgeous mail woman, convincing himself that he is entitled to all the sources of love he can consume.

Varda never passes judgement on her depraved protagonist, letting his relationship with Emilie the mail-woman grow and showing the audience new layers of his family life. When Varda finally does reconcile Francois’ two sources of love it leads to devastating tragedy, made all the more painful given how heavenly the film’s prior lightness of tone was.

This masterful directorial choice thoroughly immerses us in a character’s thought patterns, allowing us to feel and understand Francois’ perspective right in our guts. The cruel transition into sadness is as intense as any horror movie, ingraining the dangers of euphoric pride in us forever.

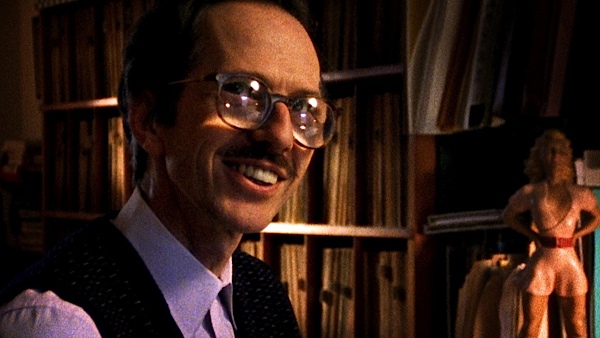

8. Crumb (1994)

On the surface, Terry Zwigoff’s “Crumb” appears to be another masturbatory celebration of its subject ala American Masters’ “Woody Allen” episode. Yet the film is less about the influence of Robert Crumb on American pop culture and more about exploring the mechanisms of using creativity and craft to deal with psychological issues.

The movie does not placate it’s subject matter as director Zwigoff takes a very off-handed approach to filming Crumb, usually just letting the cartoonist do all the talking. Through Crumb’s staggering confessions we learn of his abysmal home-life including his family’s pre-disposition to mental illness and how the usage of cartooning as a creative form of therapy more or less saved his life.

One brother stopped leaving his house and ultimately committed suicide, while another spends his days begging in the San Francisco streets and molesting women on trains. Through his cartoons, Crumb was able to exorcise his demons by putting them to ink for all the world to see yet as the documentary goes on it becomes apparent that the man still has some issues to sort out.

By not passing judgement on his subject, Zwigoff authentically and intimately captures both Crumb and the machinations of his mind. Furthermore, Zwigoff is smart to portray a diversity of outside perspectives on Crumb’s work, ranging from feminist outcries to celebrations from the editor of an erotic magazine.

Based on the range of arguments presented in conjunction with the captured depths of his mind, Crumb may be revered as genius or reviled as derogatory smut peddler. Yet no matter what one feels of the subject at the end of the movie “Crumb” remains a staggeringly resonant insight into the typhoon of mental corrosion and how one can channel it for both creativity and healing.

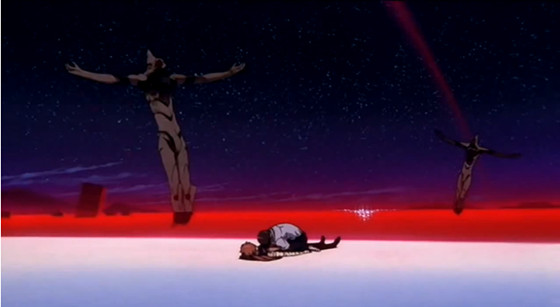

7. End of Evangelion (1997)

It is recommended that one view the original 1995-96 TV series “Neon Genesis Evangelion” before watching “End of Evangelion”, which serves as both a conclusion to the series and a culmination of what made it so powerful.

The “Evangelion” universe serves as both a foray into the depths of depression and an action-romp about middle schoolers fighting aliens with giant robots. It attempts to explore how real humans would react if put into the abstract situations befitting superheroes and how difficult it is to save the world when we don’t even like ourselves.

Shinji Ikari, our “chosen one,” has zero self-esteem. He is constantly apologizing, predisposed to self-isolation and self- pity, is mediocre when piloting his giant robot, and struggles to make even the most basic form of small talk. Ikari is not our ideal hero, he is the most cringe-worthy elements of adolescence made manifest. Yet his brutal relatability is what gives “Evangelion” its strength, particularly in the climax of Ikari’s arc in“End” whereupon he suffers a mental breakdown as the world goes into apocalypse.

Shinji and the rest of the “Evangelion” cast, rather than being ideals for us to look up to, end up barring the most horrible parts of growing up; the anxiety, the self-hatred, the fear of the future, the difficulty in connecting with others. Yet the appeal of “End of Evangelion” lies in how these characters include and transcend their inner suffering for they ultimately have to be the ones to save the world.

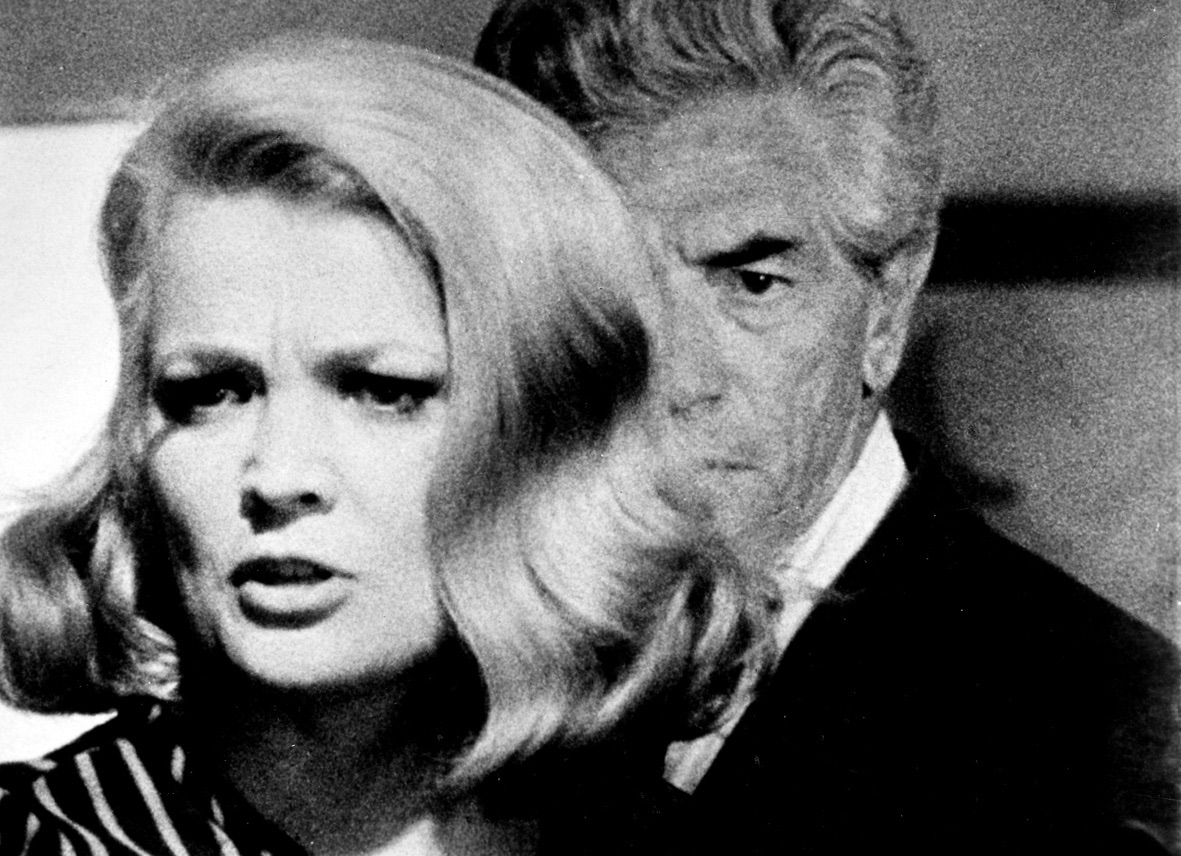

6. Faces (1968)

Few filmmakers have managed to capture the messy, awkward, chaotic, and strange rhythms of real life like writer/actor/director John Cassavetes. Many have tried to ape his style of frenetic, close-up oriented camera work as a means to make the movies as “realistic” as possible. Yet Cassavetes’ films worked because the cinematography was congruent with the improvisational-script and casts that performed as though they were ready to die for him.

“Faces” is possibly the directors most focused work, a showcase on how suburban conformity rots us and the rawness of human behavior necessary to combat it. There are no complicated camera work, set-pieces or raging monologues; it is just actors using every tool at their disposal to break the traditional artifice of cinema.

“Faces” wisely eschews a traditional plot, choosing instead to focus on how character choices and actions shape various relationships. Richard Frost is a successful businessman stuck in an unhappy marriage, and who lusts (along with various co-workers and associates) after his friend Jeannie.

Richard’s wife Maria and a group of middle-aged women attempt to re-live the youthful club scene and Maria herself even manages to seduce a young man. These scenes tend to be coated with dread, as moments of comedy and lightness seamlessly transition into despair. Cassavetes’ thesis of the hell of human relationships is a difficult one to take in, yet for the sake of bettering/understanding our connection to the human species it is vital we never look away.