5. Hard Boiled (1992)

There are a select few universal truths we carry with us all the way to the grave; the sky is blue, 2 hydrogen atoms and one oxygen make water, and John Woo’s “Hard Boiled” has the greatest shoot-outs in cinematic history. Inspector Tequila and undercover cop Alan’s quest to take down Johnny Wong’s triad is an exquisite action ballet of bullets, bodies and explosions, taking the shoot-em up to a level that has never been topped.

Yet the masterful action is only one element as to why “Hard Boiled” endures as a classic. John Woo and screenwriter Barry Wong create multi-faceted characters whose well-developed arcs strengthen the impact and tension of the action. The battle at the docks or the climactic hospital bloodbath are made all the more riveting due to investment into Tequila and Alan’s stories and in turn our fears for their lives.

Tequila’s frustration at his role in the police station, and Alan’s turmoil at having to perform morally wrong actions for the sake of keeping his cover lend “Hard Boiled” a timeless gravitas. Even Mad Dog, a nearly unstoppable gunman, has his arc given weight. We learn that he has a stringent moral code of never harming innocent people and the only reason he meets his end is because he tries to attack Johnny Wong after the Triad boss murders civilians in cold blood.

“Hard Boiled” indicates how bombastic action movies have no excuse for poor characters for while simple-plots may work best for the genre, the characters need to have as much meat and grit as the lead being fired. The action may be the crème de la crème of world cinema, yet Tequila, Mad Dog, and Alan end up being the key ingredients to the legendary dish.

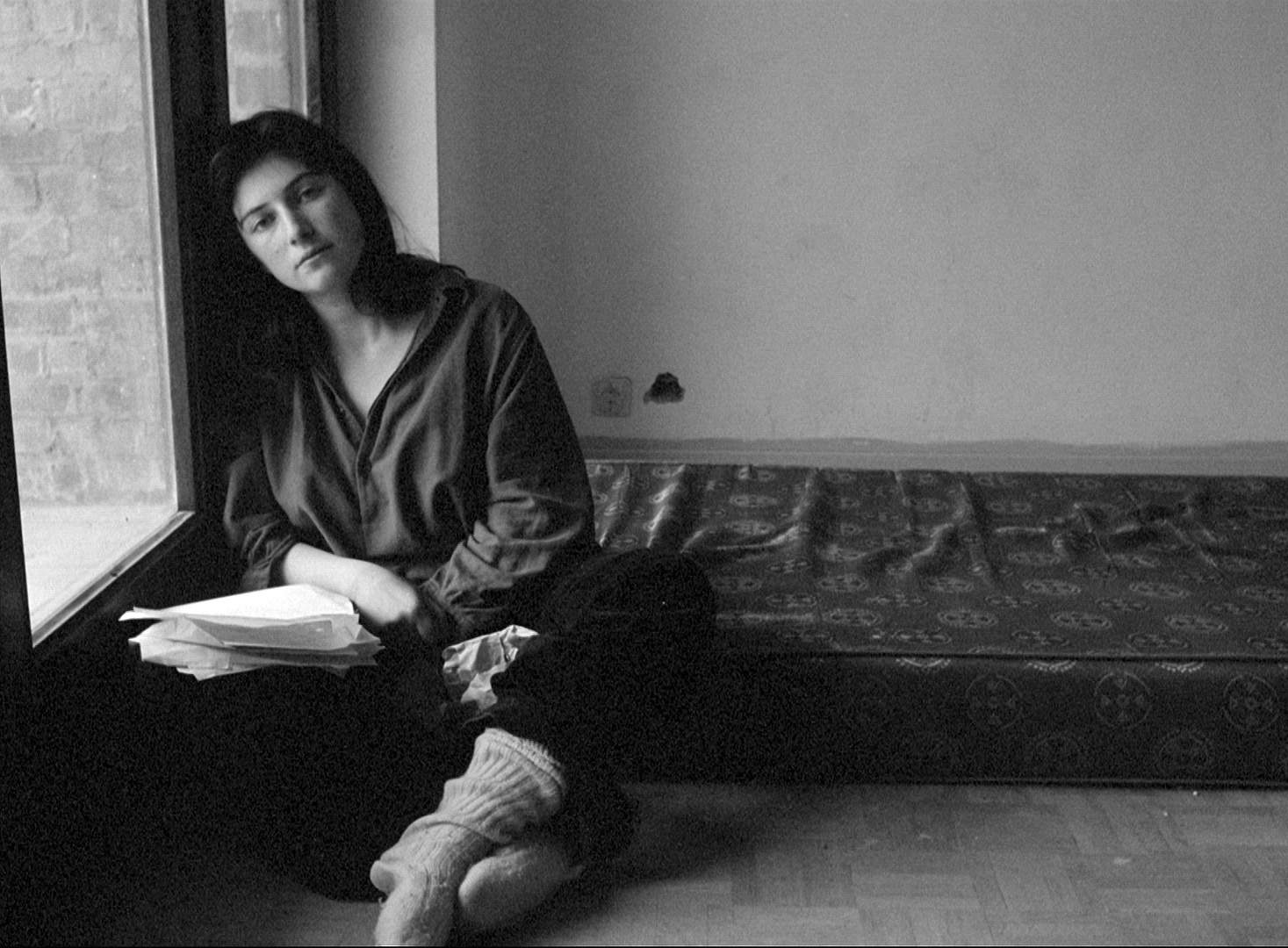

4. Je Tu Il Elle (1974)

Writer/director Chantal Akerman changed cinema with her realist work on loneliness and routine. While “Jeanne Dielman” remains her masterpiece, “Je Tu Il Elle” arguably offers a more condensed and emotionally gripping foray into compelling the audience to immerse themselves in all the mundanity and bizarreness of life as a 24-year old woman.

The pacing can be difficult for most as Akerman captures her protagonists Juli’s self-isolation in its entirety; eating a bag of sugar and loafing around on the carpet are given as much credence as sex and bar hopping. Yet this approach compliments the reality of being in your early twenties with no direction or ambition, the movie becoming scarily truthful in the process.

If one is not yet convinced of “Je Tu Il Elle’s” worth the movie also has some of the best usage of cinematic sex. The sexuality is never about eroticism as it is used instead to indicate power dynamics and character development.

One scene involves Juli giving oral sex to a random trucker she meets. The lighting is dim, with the trucker’s face being the only figure seen as he monologues about his marital problems. This direction reveals how one-sided the sex is, how it only contributes to a high for the trucker and nothing for Juli.

This is contrasted with a later scene where Juli has intercourse with an old girlfriend. The scene is bright and both figures are given congruent attention in the shot, their bodies essentially becoming one. The sex is equalizing, meant to renew something lost between the two women.

Viewing moments like this in “Je Tu Il Elle” can reconfigure our views on love and human connection, as they teach us how curing loneliness is an arduous process where we must give more than we consume. The movie can be uncomfortable because of how starkly reality is portrayed, yet we grow to adore Akerman for capturing coming-of-age so vividly.

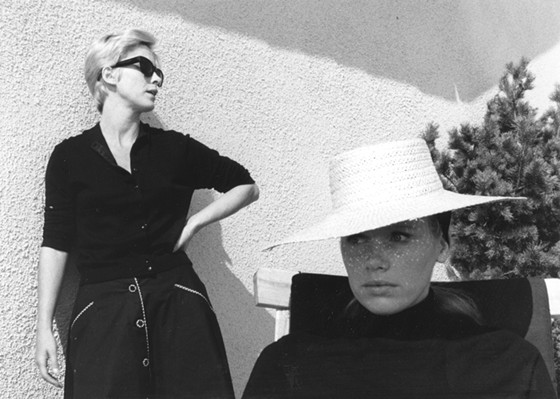

3. Persona (1966)

It’s Ingmar Bergman’s “Persona.” That’s all you need to know…

Through a complicated relationship between a nurse and a mute actress, “Persona” creates a surrealist journey into the fear of parenting, the flimsiness of identity, and the pain of vulnerability. As with “Memories of Murder”, “Persona” has a dialogue with the audience, presenting its details with cinematic aplomb and allowing us to decipher for ourselves their meaning.

The film experiments with structure and tone as a means to illustrate the mental anguish our protagonists go through. “Persona” begins with the charming development of a friendship between two women before transitioning into a drama of vindictiveness and finally full-blown psychological horror. The prologue of the movie alone signals to the audience to keep themselves on their toes, weaving strange images of cartoonish skeletons, the killing of a lamb, and a lone child calling out to a projection of what we can assume to be his mother.

“Persona” is a lesson in the relationship between surrealism and human insight as strange imagery and plot structures are best used to accentuate difficult themes. For example, the image of the child reaching out to the projected woman shadows Liv Ullman’s Elisabet’s anger at having to forgo her acting ambitions for her son. A moment where the fourth wall is broken and we see Elisabet being filmed by a production crew implies that the famous actress will never get privacy as a result of her public emotional and physiological torment.

Every camera cut adds to the movie, either through plotting or theme development, and no piece of Bergman’s wonderland is superfluous. “Persona” may be the closest approximation of what a dream is like, a full-body sensuous experience that strips its subject’s and the audience’s pre-dispositions bare.

2. Blazing Saddles (1974)

A spoof-comedy with long-form farting, a pro-wrestler punching horses, and a horny state Governor ranking above “Persona?” Blasphemy! However, “Blazing Saddles” deserves its spot thanks to its mastery of taboo comedy, a craft integral to mankind’s progress. Intelligence and critical thinking is vital in appreciating the movies transgressive and deliciously offensive jokes, as it tackles everything from race relations, political corruption, and how Mungo is only pawn in game of life.

The saga of Bart, a black man appointed as sheriff of a racist community, using his wit and cunning to take down a corrupt Attorney General, solidifies the spiritual necessity of offensive comedy. Such humor challenges our preconceptions of the world and makes us more aware of absurdity disguised as everyday norms.

Some may blast the movie for its political incorrectness, yet the comedies that stand the test of time always take a sledgehammer to decorum and “good” taste. The world of modern comedy ought to take more lessons from “Blazing Saddles” by reaffirming how cathartic and healing it is to laugh at just how stupid and disgusting human society can be.

1. Stalker (1977)

The films of Andrei Tarkovsky are full bodied immersions, where meditative environmental cinematography and unique world-building are blended with important existential debates on meaning of the universe. “Stalker” is perhaps Tarkovsky’s most human film for while it goes to great lengths to ponder the nature of desire, it is also a surprisingly touching study of broken people.

The titular Stalker takes “customers” to the Zone where it is said a person’s innermost desires will be fulfilled. Whether it is salvation or renewed prestige, Stalker’s customers believe they know what it is they want, yet they cower in the face of discovering the truth of their nature. For the Stalker himself the excursions to the Zone are all he has to live for and is content with enduring this life-style indefinitely should it mean not having to face the inner demons and sadness he constantly carries.

The movie is also a brilliant sci-fi romp as its production design illustrates how the environment can affect our mental process. The “normal” world is heavily industrialized and dilapidated wherein machinery and human “progress” has completely devoured the natural Earth. When we transition into the Zone with a genius cut, we find nature taking back human creation ala grass, trees and water overwhelming abandoned houses and vehicles. The Zone is shown to be a pocket where humanity is not the dominant entity and people who pass through must respect its rules less they be harmed.

Or perhaps the Stalker is creating a narrative for the zone to grant himself more meaning and power over his customers as he guides them to their destination. Like most of the movies on this list, “Stalker’s” strength lies in the way it manages its details to allow the audience to determine for themselves the film’s thesis.

Furthermore, the organic filmmaking and meditative pace grants an opportunity for the audience to ponder how they themselves fit into “Stalker’s philosophy. By demanding the audience’s self-awareness and mindfulness in the viewing process “Stalker” becomes a potently personal film and thus becomes forever tattooed within those who experience it.