6. Burn!/Queimada (1969)

For someone who is considered one of the great and influential actors, certainly in the cinematic world, Marlon Brando had a most uneven career. The five years which began his career in films were incendiary (thanks in no small part to the controversial stage/screen director Elia Kazan, and the 1954 Kazan/Brando classic On the Waterfront is the only Kazan film to date to make it into The Collection). However, thereafter, his career became hit or miss, to be charitable. After 1957’s Sayonara, it was all miss until the late career triumphs of The Godfather (1972) and Last Tango in Paris (1973), only to go back to hit and, mostly, miss again.

Both of those films mentioned would be fine collection editions (and Last Tango seems to be crying out for it and could realistically make it in) but there are others that are deserving. Not all of the nine consecutive flops Brando had were unworthy (and Criterion must agree since they placed 1956’s flawed but interesting Sidney Lumet directed The Fugitive Kind, a big box office bomb, into The Collection). While a number might be good Collection entries, one really worthy international effort by a fine film maker, could surely use the boost and careful restoration Criterion could provide.

Italian film maker Gillo Pontecorvo will always be remembered in cinematic circles for his 1966 masterpiece The Battle of Algiers. He made several documentaries but only a few other fictional feature films. It looked like he received a major jolt when Hollywood acting legend Marlon Brando agreed to play a principal role in a film Pontecorvo was planning centering on the mix of business, colonialism and racism (and Brando turned down two big-hits-in-the-making and his last chance to work with Kazan again in order to take Pontecorvo’s film).

The resulting film was known as Queimada throughout the world except for North America, where it was shorn of twenty (Brando-less) minutes and retitled Burn! Though set on the fictional island nation of Queimada, the film is based on events taking place in South America and the Caribbean (principally Guadeloupe) during the 19th Century.

The plot concerns British agent provocateur William Walker (Brando) coming to the sugar rich island on assignment from the British government, in league with a British company wishing to control the sugar. The object is to start a revolt against the colonial Portuguese government.

Walker finds the perfect charismatic, revolutionary puppet in Jose Delores (Evaristo Marquez an extraordinary non-professional), an angry young worker. The planned revolt comes off but,a decade later, Jose and his fellow workers find British rule even worse than the Portuguese and again revolt. Walker is sent back to quell the tumult and goes all out, committing unspeakably cruel acts against the populace, leading to devastation for all concerned (even himself).

Pontecorvo was a committed leftish political film maker and this film has nothing to soften the message, not romance, not comedy relief, not any sentimentality to sweeten the pill. Brando was also politically committed and gave far more of himself to this film than he did for most of ill-fated, too commercial projects he pursued during the 1960s.

Too bad that all of this added up to box office death, despite critical praise. Sadly, due to language soundtrack problems, the full version of the film has never been released in North America and the film in any form hasn’t been available on the home video market since the VHS era. Despite that, it does have something of a deserved cult following. This is truly the type of film rescue Criterion does so well and this could be a major item in their catalog.

7. The Mother and the Whore (1973)

There are films with troubled histories and then there is The Mother and the Whore. Jean Eustache, the director and writer (and real life inspiration) of the film is considered one of the great directors of French film history, despite a very small filmography, due to his death at age 43. That death is directly related to this film, as is also, most significantly,to another death. Due to these death, Eustache’s son Boris has long ago withdrawn this film, now widely considered one of the great French films (and films period) ever until the elusive right offer comes along. The story of the film explains all of this.

Eustache, then a young man with a passion for film, decided to follow the good advice given to almost all aspiring writers and directors: create based on what you know. In the case of this film, Eustache decided to explore a unique menage a trois relationship in which he had recently been engaged.

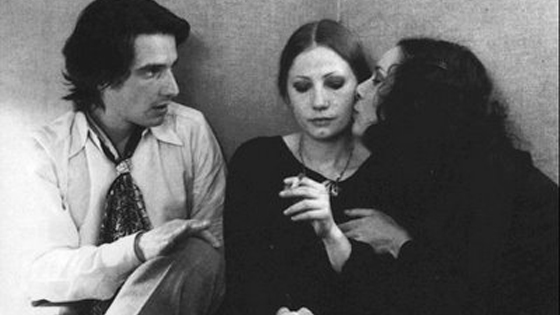

The story centers on Alexandre (the renowned New Wave actor and Eustache pal Jean-Pierre Leaud, who had a genius for stumbling into great films), a young man who yearns to create but does….well, nothing much at all. After rejection by a woman he loves greatly, he becomes attached to the maternal Marie (Bernadette Lafont), who he lets support him.

After unsuccessfully trying to return to his old love, he also meets nurse Veronika (Francoise Lebrun),who is taking full advantage of the sexual revolution. Veronika makes sure to burst in on Alexandre and Marie during an intimate moment and the three begin a mutual sexual relationship.

For almost four hours (!) the three go through many emotional and self-analyzing moments (mostly just sitting around an apartment talking)in trying to sort out their feelings and where their relationship might end up. Shot in deliberately stark black and white, the film feels improvised, yet every word was scripted.

As expected with such a bold and personal work of art, the initial reviews were mixed with progressive critics, such as Pauline Kael, praising the film and the more conventional ones dismissing it as being emotionally violent, misogynistic and formless.

However, though the tide of time would ultimately be greatly in the film’s favor, Eustache had already received the ultimate bad review. He had invited those in his life who had bearing upon the film to the premiere, including the two women who were the basis for Marie and Veronika. The woman who had been the model for the latter was distraught in no uncertain terms, thinking that the film had exposed her mercilessly for all the world to see. She went home and committed suicide.

Eustache went on to film again and quite well, but the weight of the incident tied up to his magnum opus was eventually too much to bear. Thus, The Mother and the Whore joins such other great films as The Crowd (1927) and Pixote (1980), being forever bound up with an unfortunate off-screen story.

Despite this shadow, the film is, as stated, among the greatest in the history of its own country and a notable of world cinema. Its absence is keenly felt. Criterion would surely be the perfect company to bring it back, refurbished and loaded with meaningful extras for all the world to see again.

8. 1900 (1976)

Except for certain exceptions, mostly in the 1960s and early 70s, US cinema, particularly Hollywood efforts, avoid extreme length in motion pictures, even if the story being told requires a greater length for proper telling (the advent of the TV mini-series killed off theatrical films of great length to a large extent).

However, European cinema, and audiences, seem to have a slower and more patient internal clock and,from early in film history, have been just fine with multi-hour pictures. One of the absolute acid tests for this is the mightily acclaimed Oscar winning Italian film maker Bernardo Bertolucci’s true magnum opus 1900 (or Novecento, which more accurately translates out to “Twentieth Century”), which, in its full length state, runs for some five hours (yes).

The film features an international cast including Robert De Niro, Gerard Depardieu, Dominique Sanda, Francesca Bertini, Laura Betti, Stefania Casini, Ellen Schwiers, , Alida Valli, Romolo Valli, Stefania Sandrelli, Donald Sutherland,Sterling Hayden and Burt Lancaster (as two great, if polar opposite, patriarchs, with Lancaster’s casting a nod to his role in the great 1963 film The Leopard).

The film begins on the chaotic day that World War II ends in Italy but chronologically the story open on a fateful day in 1901 (January 27, to be exact). The iconic Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi dies on that day but, on a large Italian estate, two boys are also born on that day. One will grow up to Alfredo (DeNiro), heir to the titles and fortunes of the estate. The other will become Olmo (Depardieu),a bastard child born into a family of peasant workers. (Lancaster plays Alfredo’s princely grandfather, Hayden Olmo’s rough hewn forbearer.)

The two will grown up as friends but it will become more apparent with the years that Alfredo, though not a bad man, is rather weak in morals and principals while Olmo, who stands for all the right things, is a natural leader of men. The century into which the two men were born will, as anyone knowing history knows,be one of great tumult and conflict, much of which finds its way into the lives of the two men.

1900 is a rich film in many ways. The production values, the cinematography, the music, the sets and costumes, are all sumptuous and instantly evoke a now extinct time and place. The cast is once in a lifetime and the leads, especially Depardieu, offer fine work. However, this film takes patience (and many find the subplot concerning Alfredo’s unhappy marriage of social/economic convenience to Sanda’s character rather tedious).

Then there is the matter of which cut one may see. 1900 was divided into two sections to be seen two separate weeks in many countries, a practice never used in the US. It was distributed in the US by Paramount, which had a contract allowing the company to edit the film to a manageable length. They got it as low as a even three hours in the editing, which horrified it’s maker.

Thankfully, when home video came along, the full version was released but it had to be released without rating since the US rating board announced that it intended to give the full version the dreaded NC-17 rating (and this visceral film earned it but that rating unfairly brands a film as shameful and dirty).

There was also the problem of the soundtrack since, like almost all international productions, there can never be a soundtrack which features everyone speaking in his/her own voice (as, for example, The Leopard could not due to Lancaster and French star Alain Delon mixing with a mostly Italian cast). Also, the video version were light on extras. No, this one cries out for the Criterion treatment and a glorious thing it could be.

9. The Night of the Shooting Stars (1982)

Its rare for two people to partner on making of a large body of cinematic work. Usually, oddly enough, when this does happen, the people involved are related. In modern times, the US cinema has the remarkable team of the Coen brothers. Long before them, though, the Italian cinema had the Taviani brothers.

Brothers Pablo and Vittorio (who died in April 2018 at age 88) worked together first as screenwriters then co-directors from the mid-1950s up until Vittorio’s death. Though their mutual careers were long, their time in the international spotlight began with the success of Padre Padrone in 1977 and extended through Fiorile in 1994. Though those films were notable, many think their finest hour to be a film known in their native land as La notte di San Lorenzo but better known as The Night of the Shooting Stars.

The film is a wartime drama made special by the fantastic elements with which brothers suffuse into it. The narrative is told through the eyes of an adult who was a child when the events took place, making everything naturally larger than life and full of mystery and wonder. The main plot concerns the last days of World War II and its effects on the people of a small Italian village.

The retreating Nazis plan to burn the village in order that it and its resources render no aid to the advancing American forces. The people of the village are told to go to the local church, which might be spared, and hope for the best. However, a more resourceful and spirited sub-set of the villagers decided to steal out into the countryside at night to greet the welcome new forces. Along the way they see and experience many terrible things but also find some wonderful things in the midst of the horror.

With its fine acting, excellent writing, and direction which creates extraordinary surreal images, The Night of the Shooting Stars is a film to see and remember always. The often disgruntled Pauline Kael called it “so good its thrilling”.

Sad to say, Criterion, home to so many fine film makers, has yet to open its doors to the Taviani brothers. However, The Night of the Shooting Stars is being spotlight in the retrospective section of the 2018 Venice film festival. Perhaps the time has come for a little more recognition (especially with the remaining brother, now 84, still living). That would be a wonder as well.

10. Jean de Florette/Manon of the Spring (1986)

One of the great national treasures of France with novelist, playwright, and eventual film maker Marcel Pagnol. Hailing from the earthy south of France, much of his career was spent creating charmingly whimsical stories about the colorful folk who inhabited the region. A new Pagnol work was akin to being given a sparkling glass of fine champagne.

Though he made or inspired several fine films, perhaps his most enduring contribution from this period is what is known as his “Marseille Trilogy”, three lovely stories and love, loss, and redemption played out againist the backdrop of the flavorful seaport town which were filmed first in the 1930s. The addition of these films to The Collection in 2017 was a true highlight of that year.

The latter part of Pagnol’s career took a turn, however, after the tragic death of his infant daughter. He moved to Paris and started writing novels which were much darker in theme and incident than his previous works. Those didn’t find satisfactory homes on film during his lifetime but did find great favor in that medium in the later part of the Twentieth Century.

French director Yves Robert was much acclaimed for his adaptations of the autobiographical works My Father’s Castle and My Mother’s Glory in 1990 (and Criterion could do worse than to consider these films also). However, those films were put in the sun by an earlier two part adaptation.

Pagnol had written a long two part novel collectively known as The Water of the Hills and filmed it himself (as Manon des Sources) in 1953. However, several compromises and severe cuts by the distributor left him dissatisfied with the results (and it was his penultimate film).

Decades later Claude Berri, an uneven writer-director-producer who ended up having some dazzling highlights in his career, just happened upon the novels while staying in a remote hotel and thought that it might make a good film. How correct was he!

The two interrelated films he created play much like reading a fine novel. The setting is the countryside of France just after World War I. Returning from the war is the ungainly Ugolin (a superb Daniel Auteuil), a none too ethical type who is bringing back a new “get rich quick” idea. He eventually confides in his uncle Papet (the great French singer-actor Yves Montand, in his greatest performance), a wealthy but truly underhanded type who has taught Ugolin all the younger man knows and has largely made him what he is.

Ugolin has in mind to grow carnations, a big cash crop in relation to the perfume industry of the country. Papet allows the idea is good but their land doesn’t have the ready water source it needs to work correctly. However, the land adjacent to theirs does. It belonged to a woman Papet had loved and lost and who lived away for many years before her death.

Now her son Jean (another great performance from Gérard Depardieu), a pitiful hunchback from the city, arrives with his wife and young daugher, Manon, to find a new life farming the land. While the evil pair don’t have access to Jean’s water rich land as such, they had stumbled upon the scource of the water, which they dam up in order to “starve” Jean out. The results are tragic.

In the second half, Manon (now played by the excellent Emmanauelle Beart), a bitter, though beautiful, shepardess, longs to take revenge on the two and is given a golden opportunity, ironically using much the same methods used against her father. The punchline is a tragic twist delivered to a surprised Papet (though many viewers might well have guessed at the surprise at an early point in the first film).

This was the supreme moment in Claude Berri’s career and an enormously satisfying cinematic experience. While this cinematic duet might not be a groundbreaker, it is a top-notch production. Not only are the actors exceptional, the production values (with their remarkable grasp of time and place), the cinematography, sets, the writing and Berri’s wonderful wide screen direction make this a memorable cinematic experience. Given how well Criterion did with the Marseille Trilogy, a Criterion version of this duo wouldn’t be at all out of line.

Author Bio: Woodson Hughes is a long-time librarian and an even longer time student/fan of film, cinema and movies. He has supervised and been publicist for three different film socieities over the years. He is married to the lovely Natalie Holden-Hughes, his eternal inspiration and wife of nearly four years.