6. Brazil (Terry Gilliam, 1985)

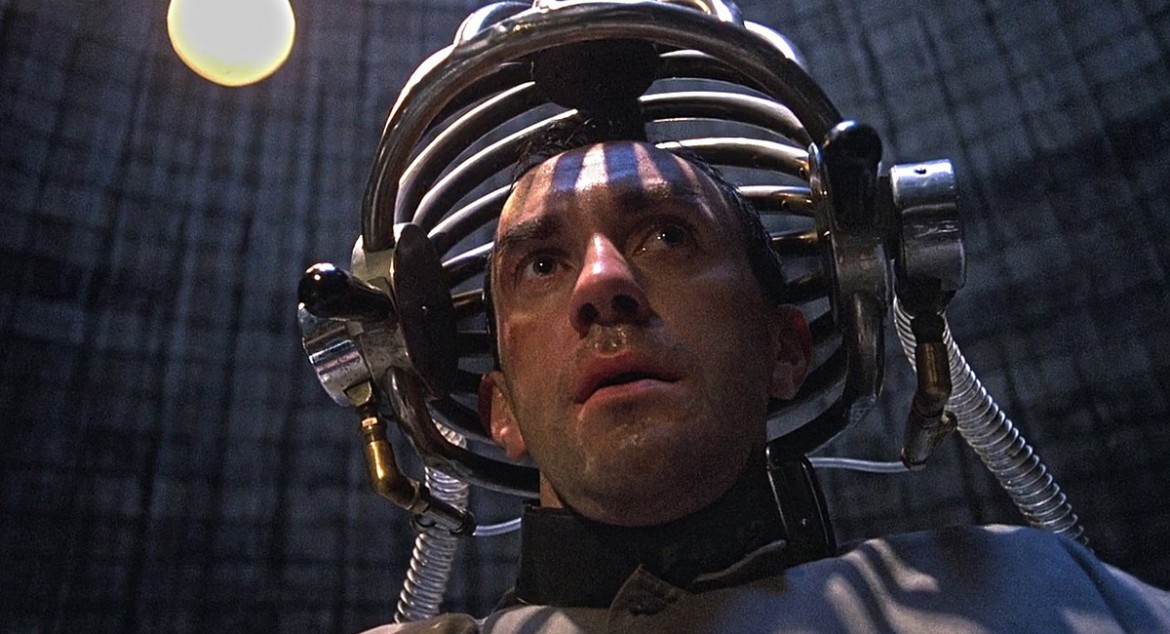

Released in 1985, only a year after the significant year George Orwell portrayed in his dystopian novel 1984, Terry Gilliam’s “Brazil” plays off as a parody to Orwell’s craft, but only at first sight.

At further examination, “Brazil” is a modernized version of Orwell’s vision of the future, but explicitly points out the absurdity of modern life. We encounter Sam Lowery, someone who is deeply integrated in the bureaucratic government, but who dreams of distant worlds. At first, he sees no point in rebelling against the dehumanizing society, but does so anyways, because he decided to follow his dreams.

Gilliam uses this kafkaesque element of the individual against the masses to display the point that, to fully embrace one’s self with the world, it is necessary to rebel. “Brazil” crafts both Lowery’s dreams and the futuristic world with an incredible love for detail, which makes it highly rewatchable, because with every viewing, new details can be discovered.

However, what makes “Brazil” such a powerful movie is, despite the comedy that clearly draws references from Gilliam’s time in Monty Python, how serious the movie takes his approach on society.

Even today, “Brazil” serves as a wakeup call to civil disobedience, but also takes into account if a rebellion against the system is even possible anymore. In the end, we only have our dreams as an escape, and maybe even that is a sort of rebellion on itself.

7. Satantango (Béla Tarr, 1994)

With a score of 8.5 on IMDb, Béla Tarr’s “Satantango” is the highest rated movie on this list, but due to the relatively low amount of votes, it still does not manage to enter the Top 250. However, this high score can show that the ones who manage to get to the end of this seven-hour long movie almost always find themselves looking back at a haunting and transcendent experience.

The plot of this black and white movie about a village set somewhere in the nowhere of the Hungarian landscape, which falls apart due poverty and corruption, could be displayed in 90 minutes.

Tarr, however, chooses a different approach, stretching his movie to the extreme. Consequently following this direction, the scenes of “Satantango” sometimes go on even after they have already ended, following the characters on their solitary way home for minutes. The many tracking shots in which this movie is filmed go on for an unusually long amount of time, creating a different experience of time.

While time in cinema is something that is artificially constructed through cinematography and editing techniques, in Tarrs’s movie the experience of time hits much closer to real life, since we get to experience the characters when they are “outside” of the story and completely on their own.

This also plays into the theme of loneliness, isolation and the effects of societal poverty that this movie portrays. “Satantango” remains a haunting requiem to humanity and as a task the viewer has to undergo, but the result is as provoking as it is magnificent.

8. Magnolia (Paul Thomas Anderson, 1999)

Featuring a cast that ranges from Tom Cruise to Julianne Moore, to John C. Reilly to Philip Seymour Hoffman, to nearly every respectable actor of the time, Paul Thomas Anderson’s “Magnolia” is an epic three-hour long examination of a single day in Los Angeles and how the lives of various individuals are connected.

It is a movie that draws inspiration from Robert Altman’s “Short Cuts,” but also stands on its own. While Altman gave a satirical, often absurd look on the American lifestyle, Anderson follows his characters and their interactions and reflects their search for humanity and understanding.

“Magnolia,” while big in its scope, remains an intimate exploration of the human condition that provides touching insight moments of deeper insight. In this portrait, every stone is set carefully, no scene feels unnecessary or misplaced, but drives the movie a bit forward. “Magnolia” ultimately culminates in an ending that is destined to alienate many viewers, probably even many who liked the movie at first, because it brings the movie to an entire new level.

Yet, the movies ending fits perfectly in Anderson’s established theme about the power of chance. Another major theme this movie explores is how the past never truly remains the past, but rather shapes our present at any given moment. This is just one of many realizations that make this movie so wise and profound.

9. Synecdoche, New York (Charlie Kaufman, 2008)

After receiving praise and accolades through his work as a screenwriter, Charlie Kaufman made his first movie as a director and was met with a confused response. It was reported that, after “Synecdoche, New York” was screened at Cannes, that the audience decided to get drunk after they watched it.

It is not hard to see where these responses come from: “Synecdoche, New York” tells the story of a neurotic stage play director who decides to make a play that is supposed to sum up his whole life. However, this task turns out to be more difficult then he thought, as he spends many years to bring the play on stage, resulting in him rebuilding New York. Just as his play becomes more confusing, the same can be applied to the movie.

“Synecdoche, New York” is a movie that starts out as a tragic comedy but then becomes larger than life, as Kaufman tries to capture life itself. The fact that he can only fail in this attempt is also something that is already built into the premise of this movie. It is an ambitious movie that blurs the line between the real and the seemingly unreal and also provides many outlooks on life that can seem very depressive.

Yet, this is something that makes this movie feel so honest. It is truly one of those rare movies where you can feel the soul of the artist in every frame. Also, a second viewing might be required, as Kaufman has included various details that add up to the premise of this beautiful film, which might stay obscured during the first viewing.

10. The Tree of Life (Terrence Malick, 2011)

Both passionately loved and almost violently hated, Terrence Malick’s “The Tree of Life” remains a unique vision in recent cinema that, to this day, needs to find its match. What makes this movie so alienating to many is probably the way Malick does not just formulate existential ideas, but rather forces them on the viewer and makes them part of the experience.

Yet, it is a movie that is not about understanding such ideas of the ways of nature and grace. Actually it is the opposite, a movie about not understanding. The infamous scene in which Malick cuts away from the plot of the movie and shows the creation of the universe, the birth of the stars and Earth and how life is formed, highlights this idea. It celebrates the wonders of creation but also shows us how small the individual is in contrast to the universe it was born into.

“The Tree of Life” contrasts the childhood of a boy in America of the 1950s with the universe that surrounds him. The depiction of the child who wanders through his home for the first time remains one of the most beautiful segments of the film, because the same wonder and amazement that the cinematography of this film holds within them is reflected in the eyes of this child.

In the end, “The Tree of Life” will never be regarded as a movie that pleases everyone, but it is one of the movies of this century that will surely not be forgotten.