5. The Bunny Game (Adam Rehmeier, 2011)

Along with the likes of Koji Shiraishi’s Grotesque and James Cullen Bressack’s Hate Crime, Adam Rehmeier’s 2011 film The Bunny Game was refused classification by the BBFC, in this case for its portrayal of sexual violence. Although it’s a distressing viewing experience, it isn’t necessarily infamous for what it shows, but for its perplexing casting.

The film is based on true events, of which allegedly happened to actress Rodleen Getsic – playing a version of herself in the role of Bunny. She claims to have been abducted on more than one occasion, and here she dramatises one of the horrifying situations she tragically found herself in. A prostitute is left fighting for her life, chained and gagged in the back of a lorry by a merciless trucker – to survive, she must use all of her strength to narrowly escape a grisly fate.

The visuals are as disturbing as one would expect, but most audiences find the most troubling aspect of the production to be Getsic’s involvement with it. The ordeal that the film depicts is not for the faint-hearted, and one reasonably begins to question why someone would wish to put themselves through that again, whether for the purpose of “art” or not.

There is something profoundly upsetting about watching someone put themselves through something that must have been absolutely devastating, and to present it so viscerally for an audience.

Perhaps the actress saw it as a way of telling her story and expressing the traumatic experiences of her life, but it feels as if we are witnessing someone being punished, except this time it feels uncomfortably genuine. The sex acts the film depicts are real, and most have agreed that this was entirely unreasonable.

Despite the actresses best efforts to tell her story, The Bunny Game is unsuccessful as a piece of cinema, sadly feeling like nothing more than a sadistic and cheap experiment, and a waste of its victims cooperation.

4. Baise Moi (Virginie Despentes, Coralie, 2000)

Regraded by British press as “the most sexually explicit film to ever reach our cinema screens”, Baise Moi – translating as Rape Me – is a French artsploitation film containing huge amounts of controversial material. The film is considered by most as one of the weakest examples of the French new extremity wave which prospered at the dawn of the new century, dull in comparison to such great works as Gaspar Noe’s Irreversible and Claire Denis’ Trouble Every Day.

Despentes’ film tells the story of two young women who decide they can no longer suffer at the hands of their uber-masculine environment. After being subjected to violence, rape and degradation they unite and embark on a murderous road-trip, brutally destroying anyone that gets in their way.

Helmed with a strong feminist ideology, Baise Moi had the potential to be a really interesting and important piece of work, but instead ended up feeling exploitative of the very characters it wished to justify. We should console the victims and empathise with them, rather than rejoice as they become the monsters that drove them to such rotten deeds.

The film’s biggest sin is that it fails to generate a powerful discussion, and feels like the cinematic equivalent of someone shouting strong views at someone who has passed out; there is no dialogue between two platforms, just loud and obnoxious bulldozing barely disguised by independent trash-aesthetics.

This punk-rock approach to sculpting a cinematic statement outraged many who accused the film of being shallow and half-baked. There are those who disagree and believe the film to be very successful in communicating a strong and empowering message – it would be an idea to reassess it after so many years, however, that feels a rather dull proposition.

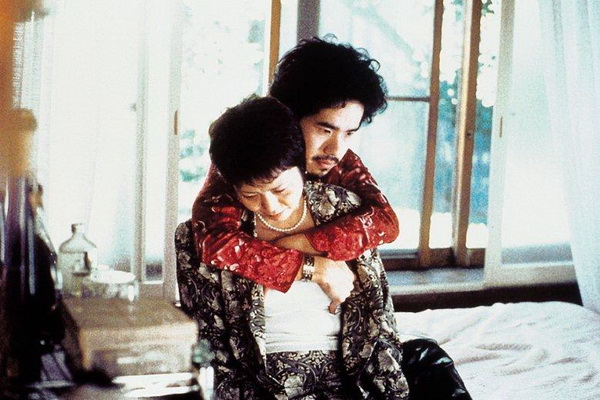

3. Visitor Q (Takashi Miike, 2001)

Legendary Japanese filmmaker Takashi Miike is no stranger to controversy, and although his 2001 family-drama isn’t among his most regarded, it is certainly his most perverse – angering many and hitting just the right note with his devoted following. It’s comedy painted pitch black, and may actually be one of his greatest achievements – in an odd way.

Visitor Q follows a Japanese nuclear family who are far from the normality that their conventional unit would suggest. A mother is beaten regularly by her bullied son, which the father begins to document with complete enthusiasm when a stranger arrives at their home after he randomly assaults the cowardly patriarch; their behaviour is altered furthermore by his residence, leading to all sorts of macabre and unbelievable actions.

It’s a film concerned with characters that no one would ever wish to spend time with, and somehow Miike’s unapologetic approach to displaying them makes that time bewilderingly entertaining. Those with expectations follow the narrative fully aware that the subjects of the film will further decline, becoming more twisted and deranged as time goes on.

Nothing is off the table: incest, prostitution, necrophilia, drug-use, murder – a list of taboos are addressed and included, resulting in a film that almost feels to be a celebration of free cinema, and a testament to what certain filmmakers are able to get away with it. The film is infamous for the reasons listed above, and additionally for the film’s morality, choosing not to punish their actions in the concluding moments but instead bring the family closer together.

Miike has conjured a despicable microverse, a family like no other; just like Q armed with a brick, he is unafraid to bludgeon us over the head with this vision.

2. Slaughtered Vomit Dolls (Lucifer Valentine, 2006)

Working under a pseudonym, controversial Canadian filmmaker Lucifer Valentine single-handedly coined the subgenre of “Vomitgore” back in 2006 with Slaughtered Vomit Dolls – many have questioned whether this is an achievement at all. Nevertheless, the director has carved out his very own niche in the realm of underground extreme cinema, and has cultivated a loyal and dedicated fanbase.

Although taking an abstract approach, Valentine’s first film of the “Vomitgore” trilogy centres around the demise of a nineteen year old bulimic stripper, whose mind has plunged into psychological torture. The film is seemingly made up of a series of shocking and offensive images of gore and excessive vomiting. Littered with sexually explicit and graphic material, it is our immediate instinct to begin searching for meaning behind these acts.

However, it becomes clear rather quickly that the film is an outlet for the director’s supposed fetishes – even then, his shocking statements regarding incest and torture may be mere fabrication, helping to sell a product such as this to those who believe that Lucifer Valentine may be the “real deal” amidst a sea of edgy gorehounds.

Although it has resonated with a very select few, many who have watched the film agree that it is hard to bestow with any merit other than nausea – is that a merit? I’m sure if you were to ask those who enjoy the film, they would say that it most certainly is. It feels much more like a sadistic art-piece, or an experiment, rather than a feature-film.

The film’s title is a clear indicator of its content, so it would be reasonable to think that those who go ahead and watch it will know what they’re in for and appreciate it – shockingly, even those that watch it, fully aware of its title and content beforehand, end up detesting it.

It is very possible that many who watch it are simply curious, but Valentine’s films have gained a very loyal following all the same. These fans likely take pride in heralding films that many cannot access or connect with, and that’s fine – they can have them.

1. Melancholie der Engel (Marian Dora, 2009)

Without a doubt the most offensive film on this list, Marian Dora’s arthouse-horror epic has developed a cult following since its release in 2009, even spawning a recent documentary: Revisiting Melancholie der Engel.

It would certainly be considered the most controversial film ever released if more people were even aware of its existence. Anyone who has seen it is unlikely to forget it, and over the years, it has become apparent that many have failed to watch the entire film despite their best efforts; an almost three-hour endurance test that even the most seasoned of audiences have found impossible to tolerate.

The film follows two friends who reunite after many years of separation, gathering others and whisking them away to a remote house. For Dora, nothing is off limits, and he appears to have gone through great effort to break every taboo possible: hardcore drug-use, sexual violence, mutilation, blasphemy, and real-life animal cruelty.

Melancholie der Engel contains a substantial amount of alarming material, and those who see it through to the end are likely to feel physically and emotionally drained, desiring nothing more than to watch something life-affirming immediately afterwards. It is clear that the creative team involved wished to make the most shocking film possible, and although this has clearly been the ideal of numerous extreme filmmakers, those involved evidently desired to make it artistic also – whether it achieved this ambition is still debated by cult audiences.

Perhaps more surprising at this point is that the film boasts a pretty superb score, and there are certain shots that suggest an artistic streak – a spider made to appear gigantic climbing against a mesmerising skyline is just one example. These are clearly individuals who maintain some degree of skill for their craft, but ashamedly, they instead prioritise shock-value and a cruel entitlement over other living things.

As the film gradually pursues its own self-prepared downward spiral, accomplished cinematography and potential meaning surrenders itself to pretentiously executed torture, and any merit it once had is totally abolished. Cinema doesn’t get more infamous than this.