8. Winter Light

This Swedish film takes place in close to real time, as the pastor of a small village church undergoes a “dark afternoon of the soul”. We see this pastor performing all the menial duties of his position, but quickly become aware that he is just going through the motions while facing a soul-shaking crisis. Or is he just tired and a little sick? It’s clear that the man needs some sleep, and a nagging cough has him on the verge of collapsing in exhaustion.

Nevertheless, his crisis of faith is real, and presented here for our consideration: during this afternoon we observe his interactions with a dedicated and eager to please church assistant, a young father driven to almost speechless despair and paranoia over the idea of an impending nuclear crisis, and an agnostic schoolteacher who attends the church because she finds herself in love with its leader. The spiritual trial the pastor undergoes will have a profound effect on each of these people under his guidance, as he searches for his own answers.

Winter Light is one of several films made by Ingmar Bergman in which the silence of God is considered. Aside from the various revelations in which believers of all kinds choose to put their faith, God’s lack of active communication with people must be acknowledged at some point by most of us.

While it is an ever present reality, this silence is felt especially keenly during difficult times in life, and the winter day of this film is just such a season. How this professional man of God handles this silence, knowing that the outcome will affect not only him, but also those looking to him as an example, is a deeply personal experience in which the viewers of Winter Light are invited to join.

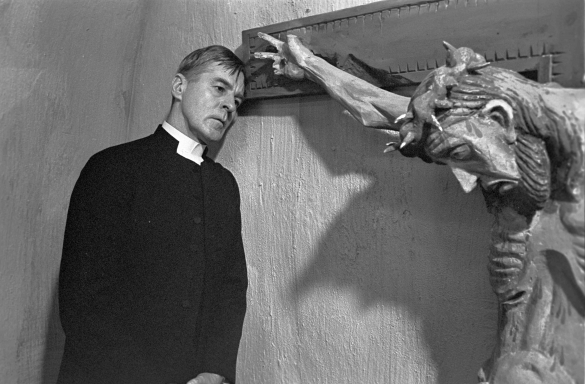

7. Blue Velvet

No one can shine a light on the shadows of small-town America like David Lynch.

From the opening minutes, Blue Velvet announces itself as a film with two faces, and with its main character we will go on a revelatory journey that shakes us to our core. The opening sequence takes us down an idyllic American Main St, full of smiling people waving in slow motion; suddenly the camera takes a symbolic dive beneath a green lawn where black beetles burrow and joust just out of sight.

The message is clear: there is more to any seemingly ideal society than what meets the eye, and its secrets are just as real as its polished veneer. When our hero Jeffrey Beaumont stumbles across a severed human ear in a field, we cross with him the bridge between these two worlds.

Charlotte Brontë mused about the villain in her sister’s classic novel Wuthering Heights: “Whether it is right or advisable to create beings like Heathcliff, I do not know: I scarcely think it is.” Such a character is Frank Booth, the tormentor of all who enter his kingdom beneath the metaphoric green grass of this city. He is cruel, twisted, and difficult to watch on the screen; but he represents a dark element of society that the director wants us to understand and acknowledge.

In a scene of startling transcendence, Jeffrey struggles to understand why such people exist in the world. This film wants us, and him, to understand that the darkness of evil can be overcome and driven away only by the light of love. Unlike much of Lynch’s work, this story has clearly defined good guys and bad guys, and the battle between the two is hard won.

6. Stroszek

German filmmaker Werner Herzog takes his cameras and creative talents to America in this unique and original film. The story follows the fortunes of Bruno Stroszek, a street performer whose recent trouble with alcohol has landed him in trouble with the Berlin police. Upon his release, Bruno decides to make the move to America along with a local prostitute trying to escape her abusive employers, and a neighbor whose relative has invited them all to live on his farm in Wisconsin.

What follows is an unsentimental examination of the American Dream, which the German trio finds to be slightly less blissful than U.S. postcards had indicated. Unfortunately, these eccentric and hapless characters do not gain either wisdom or common sense simply by virtue of their move, and their new country does not magically envelope them in wealth and success.

While Bruno and his friends are not bullied and abused by pimps like they were in Germany, they discover that bill collectors and bankers are no less determined to protect their own interests and collect what is owed them, albeit with a smile instead of physical violence.

Herzog uses mostly locals and non-actors to populate his film, and the results are both comical and deeply affecting. The unforgettable and iconic final scenes of Stroszek externalize the private chaos into which Bruno has descended, largely due to his misplaced expectations.

While this film has nothing against any particular country, it certainly shows that the American Dream has a downside and can devour some as quickly as it frees others. It’s a touching, quirky story that fascinates us while raising the question: Is freedom always an absolute good for everyone?

5. Silence

Is there anyone more hopeful, idealistic, and potentially naïve than a young person fresh out of seminary? The young Jesuit priest at the center of this film is armed with an unshakeable faith, but is less aware of the latent spiritual pride which often accompanies such zeal. He and a friend volunteer to leave Portugal for Japan in search of their mentor who, rumor has it, has apostatized (denied his faith) and adopted the culture and religion he set out to convert. They are convinced they can change his mind.

What these devout friends find waiting for them in Japan shatters all their preconceived notions. Most Japanese are in fact quite comfortable with their ancient religion and not eager to convert; what few Christians exist are under severe persecution and have to worship in secret.

As priests, they are subjected to even more severe treatment as the disruptors of an established culture, and the missionaries find themselves facing, step by step, the same challenges that must have greeted their mentor many years ago.

By the time the novice comes face to face with the apostate, his own faith has been deeply shaken by the conditions in Japan, and he finds God maddeningly silent as his moment of decision draws near. If a public betrayal of his faith allows him to continue spreading that faith in secret, while a public affirmation will cost not only his life but also those of his friends, what is he to do? The line grows blurry between pride of saving face and genuine allegiance to God.

The realization that saving the life of another might mean the loss of personal salvation becomes frighteningly real. When no divine voice offers an answer, can love for that divinity be separated from love for a friend a few feet away? It is within this vast silence that our most important decisions are often made.

4. The Elephant Man

As this film takes care to point out, people are frightened about what they do not understand; the plight of John Merrick, the physically afflicted center of the story, is one indeed difficult to understand.

John was a real person living in Victorian England who suffered from elephantiasis, a severe physical deformity, and his very existence was the catalyst for an examination of how different people handled their fearful reactions to him.

After spending most of his life as part of the freak show wing of a traveling circus, with an “owner” as cruel as he was greedy to exploit his most prized possession, a kind-hearted medical doctor discovers Merrick’s plight. He exerts great effort to remove the unfortunate man from his humiliating lifestyle, but then must face his own motives when high society’s attention to Merrick brings the doctor professional success.

Merrick, and through his life the audience, is exposed to the very best and the very worst of humanity throughout this film. Having been treated with so much hate, if his view of human nature becomes dark and cynical the audience will offer little protest; but, if the instances of love he experienced are enough to preserve his faith in others, who are we to disagree with his judgment?

Still, the efforts of even the best-intentioned people to treat Merrick as an equal sometimes fell flat, and this film examines whether people like its protagonist will, through their noble natures, transform society or be destroyed by it.

3. Breaking the Waves

Bess talks to God, and God talks back to her…in Bess’s own voice. The grim-faced, severe church elders in her small Scottish community are naturally not thrilled by Bess’s eccentric behavior, and most of the town considers her mentally ill. But, when she falls in love with and marries an outsider to the community who loves her simple and genuine heart, Bess finds her ultimate happiness. Alas, this feeling of fulfilment is not to last, as her husband suffers a horrific, paralyzing accident.

In Bess we have a character with two endearing but potentially combustible qualities: a deep devotion to a God who speaks directly to her, and a consuming, sacrificial love for a man for whom she would give anything. She becomes obsessed with the idea that through sacrificing herself – her body, her reputation, her security – her husband can be healed, and she throws herself into this purpose without any care for her own well-being.

The sacrifice of one worthy person for the salvation of another is an original element of Christian theology, but here we’re asked to consider whether the effects of this principle are still at work today. Yes, her journey is difficult to watch, for we’ve grown to love this character, and hope that her God will protect her sweet simplicity. But the viewer will be forced to wonder if, at least by the standards of her own religion, Bess has become a sinner whose soul is now in danger of eternal judgment. And what of the efficacy of her actions to bring healing to her husband? Whether or not a modern miracle occurs, Breaking the Waves has volumes to say about the value of a pure heart’s sacrificial love, and this lesson alone is worth the journey.

2. Ordet

Let’s talk briefly about Søren Kierkegaard, the Danish philosopher and theologian whose ghost haunts this Danish film. Johannes, a sensitive scholar and one of the main characters, believes himself to be Jesus Christ. The reason he has gone mad? Reading too much Kierkegaard. As a writer, Kierkegaard often tackled the topic of faith – faith that flies even in the face of rationality at times, because it believes in a higher purpose.

Faith is the focus of this film, and is a wildcard of as yet unknown power; was Jesus being colorful when he said that a tiny grain of faith could move a mountain, or was he laying it out for us as clearly and literally as he could?

This story highlights many aspects of faith: its pettiness and inflexibility, as Protestant factions within the town squabble and refuse to allow their children to marry; its strength, as the story’s patriarch faces unbelievable tragedy with stoicism and patience; and its simplicity, as Johannes and his young niece form a strong bond based on their mutual and unquestioning belief.

Most of all, this film wants to teach us the power of faith as we suffer with these characters, desperately hoping that God has not forgotten them. By the end, we find ourselves rooting for a faith that flies in the face of reason, and even begin to wonder if what can be accomplished by faith is limited only by our lack of it.

1. Rashomon

Here is the ultimate examination of subjectivity, which is intended not to advocate for any singular worldview, but to reveal the inherent weakness and limited nature of any one perspective.

The only objective facts presented by this story are that a crime has been committed and that there have been several witnesses. The film proceeds to describe the crime as seen through the eyes of each witness, but we soon become aware of startling differences between their accounts, each of which throw us into greater confusion about what actually happened.

These conflicting accounts cannot be explained away as simple lies, though each tale does tend to cast its teller in a favorable light; no, more complex forces are at work which reveal the unconscious and subconscious biases of the witnesses, and open windows into each of their worldviews.

The real riddle is whether the witnesses are convinced that their version is actually what happened, or whether they are intentionally altering small elements of the story to their advantage. Can one’s worldview be so entrenched that it literally distorts the report of one’s senses in order to avoid losing its power? Facing unflattering truths about ourselves is not easy, and only vigilant self-examination can keep self-delusion at bay.

In addition to examining the personal perspectives of those who saw the crime, Rashomon also poses questions about the nature of reality itself, and whether or not our human senses might be inherently flawed or limited as instruments that report to our consciousness.

The viewer will be forced to consider which account is true, and why? Or, is each one completely false, and the truth unknowable? Or, perhaps each story is in some way true but incomplete. Whether or not this brilliant Japanese film actually reveals the correct version of events is something for you to discover.

Author Bio: Martin Wilson is as enamored of great films as he is of tennis and classic literature. As often as possible, he slips the surly bonds of North Carolina to go galavanting around Europe with his lovely wife, who correctly reminds him that addressing his audience as “gentle reader” is not as clever as he thinks it is.