8. Fahrenheit 451 (1966)

Ray Bradbury is, without a doubt, one of the greatest figures of science fiction literature and “Fahrenheit 451” is, perhaps, his greatest and most influential work. This film adaptation, directed by François Truffaut and photographed by Nicolas Roeg, is nothing but a wild ride of dystopian darkness.

In a obscure future, every literature book is destroyed by an organization known as “Firemen.” Guy Montag (Oskar Werner) is part of this group. One day he meets one of his neighbors, Clarisse (Julie Christie), a young school teacher. They go to a coffee shop and discuss Guy’s job. She asks him if he has ever read one of the books he confiscates. When he returns, the questions of Clarisse still linger on his mind. There, his wife (also played by Julie Christie) is watching the “The Family,” the most beloved and popular tv show in the country.

In the world that Truffaut depicts, it seems that society is hypnotized with audiovisual media. Words and meanings are banished from the public sphere because they make people think, and when people think, they start to distinguish among themselves. For Truffaut, ultimately “Fahrenheit 451” is a film in homage to ploys. And ploys are the ideal means of resistance.

9. Blade Runner (1982)

Watching “Blade Runner” for the first time is a life-changing experience. The film’s legacy is unquestionable and has forever shaped, just like Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” and Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey,” audience expectations about science fiction as a film genre.

Los Angeles, 2019. Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) is a former “Blade Runner”; that is to say, a police officer who hunts and kills biorobotic androids known as “replicants.” These bioengineered beings are manufactured by Tyrell Corporation. One day, he’s busted by Officer Gaff (Edward James Olmos) and driven to the office of his previous boss, Bryant (M. Emmet Walsh).

The two watch a video where Holden (Morgan Paull), another Blade Runner, implements the “Voigt-Kampff” test. This examination can tell who is a replicant and who is not. The investigated, Leon (Brion James), kills Holden. Consequently, Bryant orders Deckard to search and kill Leon and the other three Nexus-6 replicants: Roy Batty, Zhora, and Pris.

The cosmical and spiritual condition of the replicants feels, at the end of the movie, like a mirror of the inner struggles that Deckard suffers. The rhythmic structure of the film alludes to a classic cop-criminal persecution, but the truth is that what Deckard is chasing are the existencial limits of his own life.

10. THX 1138 (1971)

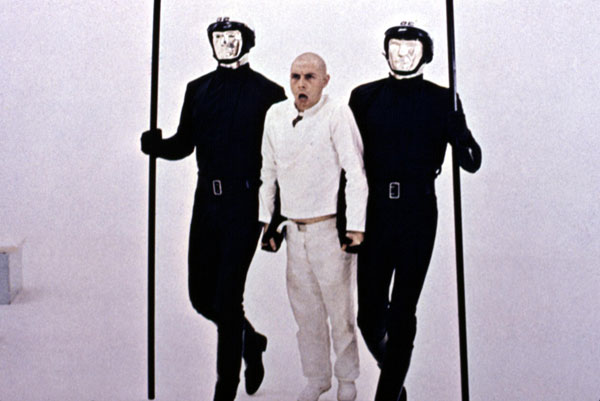

George Lucas’ student short film “Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1138 4EB” served as the basis for his first feature “THX 1138.” Set in a dystopian world that feels at times very much like Orwell’s “1984,” the film displays a memorable ambience of claustrophobic anxiety that is difficult to forget.

In the future, love, sex, emotions and the concept of family are crimes. Difference is also penalized, so everyone has to look the same, with identical uniforms and shaved heads. Nevertheless, the police and the monks use distinguishable clothes. THX 1138 (Robert Duvall) works at a factory that produces police droids. His roommate, LUH 3417 (Maggie McOmie) works at CCTV control centers monitoring the order of the city. Eventually, she changes the drugs that inhibits the habitants of this world to be able to feel passion. For this reason they both fall in love and try to escape from this oppression.

Although it is possible to find a similar attitude toward visual grandiosity that was later used in “Star Wars,” in this early George Lucas effort, it is more important to focus on the world that the American filmmaker decided to create; that is to say, a particular and rare environment that allows for immersive stories to happen.

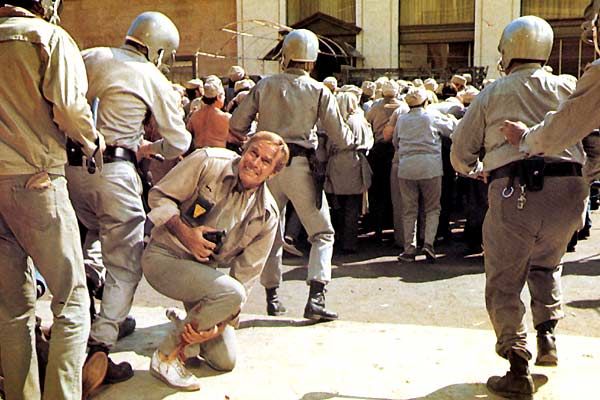

11. Soylent Green (1973)

In the future, it’s very possible that some environmental conditions such as the ones that “Soylent Green” presents will restrict everyone’s lives. Consequentially, it’s the predictive vision of the future that makes this Richard Fleischer’s film unforgettable.

In 2022, Earth is in a pitiful condition. Pollution, overcrowding and climate change are devastating our planet. To solve the problem of a lack of food, Soylent Corporation has created Soylent Green, a food supply based on plankton that will solve this important issue. Detective Frank Thorn (Charlton Heston) and Sol Roth (Edward G. Robinson) suspect that something is wrong with this new type of food.

As Jim Knipfel states about “Soylent Green,” “But none were as immediate, detailed, realistic or relevant as Richard Fleischer’s 1973 film, and none presented quite so bleak a picture of the human misery that could result from unchecked overpopulation, global warming, and food and energy shortages. The world Fleischer envisioned on the MGM backlot was one you could almost smell.”

12. Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956)

The era of McCarthyism was characterized by an omnipresent paranoid mood in American society. Anyone could be accused of being a communist secret agent installed in the U.S. Even close relatives could be possible suspects. Accordingly, “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” illustrates this attitude in a very skillful way.

Near Santa Mira, a fictional town in California, Dr. Miles Bennell (Kevin McCarthy) presences a large number of apparently Capgras delusion (a medical condition whereby patients feel that close people have been replaced by impostors). Eventually, Dr. Bennell meets one of his ex-girlfriends, Becky Driscoll (Dana Wynter). Becky’s cousin Wilma (Virginia Christine) fears that her Uncle Ira (Tom Fadden) is, in fact, an impostor. Although some physicians claim that this may be a case of mass hysteria, this strange behavior will prove itself as the opposite.

The allegorical use of vegetable pods, which transformed themselves into imitations of human beings, symbolized perfectly the fear that many Americans had at the time, namely, to be invaded by a foreign destructive ideology.

13. World on a Wire (1973)

In his brief but intense career, German filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder produced some really great films. In this regard, “World on a Wire” is his only work of science fiction. Based on the novel “Simulacron-3” by Daniel F. Galouye, the film tells a paranoid story about simulated reality, commercial bonds, and political intrigue.

In Germany, the “Institute for Cybernetics and Future Science” has developed a new computer program called “Simulacron.” The program hosts an artificial world where 9,000 “identity units” live a simulated life unaware of its fakery.

The goal is to be able to predict mankind’s mistakes in order to avoid them in the future. Professor Vollmer (Adrian Hoven), who serves as a technical director of the institute, has discovered a secret that will jeopardise the project. Nonetheless, he dies in an enigmatic accident. His replacement, Dr. Fred Stiller (Klaus Löwitsch), will have to face the mysterious events that will occur at the institute.

This paranoid thriller, mixed with Fassbinder’s unmistakable directing style, may be one of the most overlooked science fiction films of all time. “World on a Wire,” originally conceived as a TV film, was one of the first movies that proposed the use of computer simulation as structural scenery for a story to happen. Its seductive and irresistible ontological mystery, along with its colorful and amazing photography, make “World on a Wire” a fascinating cinematographic experience.

14. Videodrome (1983)

David Cronenberg’s astonishing masterpiece “Videodrome” blends science fiction and thriller in a very unique and original way. Regarded as a “techno-surrealist” film by Daniel Dinello, the movie depicts the search for the most exciting TV content through storytelling that features both technological instruments and intriguing plot devices.

Max Renn (James Woods) is the boss at CIVIC-TV, a Canadian TV station dedicated to scandalous and shocking television. He’s looking for impressive new content for his channel. Eventually, Max goes to Harlan’s office (Peter Dvorsky). There, Harlan shows Renn ‘Videodrome,’ a weird television network apparently broadcasted from Malaysia that depicts cruel and barbarous murders. Max falls in love with this type of show and decides to use it in his own television station.

Cronenberg thinks that technology is an “extension of the human body”; that is to say, body and machine can not be separated. In “Videodrome,” this notion is displayed by one of the most exciting ideas any filmmaker has ever brought into the medium: the new flesh, a concept that questions humankind’s existence as material beings into the world.

15. Alien (1979)

Ridley Scott’s fierce tale of an extraterrestrial creature that hunts a whole crew of space merchants has positioned as one of the landmarks of cinema as an artistic expression. Its hostile filmic tone and menacing atmosphere has remained in audience memory as a brand that has shaped maybe every confrontation with films that try to merge science fiction and horror. But it’s the thrilling aspect that stands out in “Alien.”

The spaceship Nostromo is returning to Earth after a very long commercial trip. Its crew consists of Captain Dallas (Tom Skerritt), Warrant Officer Ripley (Sigourney Weaver), Navigator Lambert (Veronica Cartwright), Executive Officer Kane (John Hurt), Science Officer Ash (Ian Holm), and engineers Brett (Harry Dean Stanton) and Parker (Yaphet Kotto).

The ship’s computer, Mother, awakens the crew due to a message from planetoid LV-426. They have to investigate that message due to company orders. When they arrive into the planet, they find out that the signal comes from an alien spaceship. Inside, Kane discovers a chamber with a lot of egg-like elements. A living hell is imminent.

“Alien” is stunning because it always keeps the audience not just wanting Ripley to be saved, but also wondering about the origin of this weird creature. As Roger Ebert claims, “The result is a film that absorbs us in a mission before it involves us in an adventure, and that consistently engages the alien with curiosity and logic, instead of simply firing at it.”