8. Taste of Cherry (Abbas Kiarostami, 1997)

“Taste of Cherry” touches on the always complicated and divisive subject of suicide. While such a theme might bring out tons of ethical considerations, the film doesn’t try to decide whether it’s right or wrong to take your own life; instead it just portrays a man who has decided to kill himself, and is looking for someone who is willing to bury him after he ends his life. The minimalism in the cinematographic language allows for a very intimate and personal portrayal of the protagonist, one that seems like it was taken out of a documentary.

The film flows like a poem. It consists mainly of scenes where the protagonist is talking to somebody else, proposing a sum of money if they decide to comply with his demands. His interlocutors always express their views on the subject of suicide, most of them trying to talk him out of his decision.

When the film ends we don’t know if he decided to change his mind or if he maintained his position and his plans; the film is not about the character, it’s about the viewer, about everybody who has ever considered suicide. “Taste of Cherry” wishes to establish a conversation with them, to make them see things in a different way, to consider different opinions before making a definitive choice.

9. Chungking Express (Wong Kar-Wai, 1994)

Known for his teenage dramas in which he portrays the violence and the hopelessness felt by young adults paired with a unique visual aesthetic, Wong Kar-Wai is one of the most important filmmakers today, one who, despite his somewhat scarce filmography, has already earned his place in the history of the medium. He has struck a deep nerve particularly with young people, who feel great empathy and identification with the characters and situations explored in his films. There is an inescapable aura of ennui and sadness that underlines all of his oeuvre that is very common to the process of growing up.

Two stories intertwine in “Chungking Express.” Two melancholy policemen going through difficult breakups are the starting point of each them. While one of them obsessively buys one can of pineapple everyday with the expiration date the same as his birthday for a month in hopes his loved one will come back before he buys 30, the other spends his time consoling his department, trying to talk inanimate objects out of their grief and sadness. Merging tenderness and desolation, “Chungking Express” is a fantastic film about the loss of love and the unexpected emergence of a new one.

10. The Seventh Seal (Ingmar Bergman, 1957)

A lot has been said about Ingmar Bergman. He is the favorite filmmaker of everybody’s favorite filmmaker: a poet, a philosopher, a magician who used cinema as a tool to explore the deepest and darkest recesses of the human mind.

Often referred to as “the last existentialist,” his films are often about characters confronted with the realization of the meaningless of life, of the lack of an intrinsic value given by religion, work or love. Many masterpieces can be attributed to his name, such as “Wild Strawberries,” “Summer with Monika,” “Winter Light,” “Through a Glass Darkly” and his most famous one, “The Seventh Seal.”

“The Seventh Seal” is probably the most allegorical film in Bergman’s filmography. It tells the story of a crusader – played by the incomparable Max von Sydow – during the times when the black plague was eating Europe’s heart. Death appears before him with the purpose of taking his soul, but he doesn’t want to die just yet, so he challenges Death to a game of chess; if he wins Death will leave him alone, but if he loses he will agree to go.

The character, when faced with mortality, is desperately looking for meaning wherever he can, but Death’s shadow is constantly looming over him, just waiting for the final moment when it will be able to take what it wants. The self, society, art, entertainment, fear and, of course, death, are just some of the many themes touched by this film that will undoubtedly leave a profound mark on anybody who dares to see it.

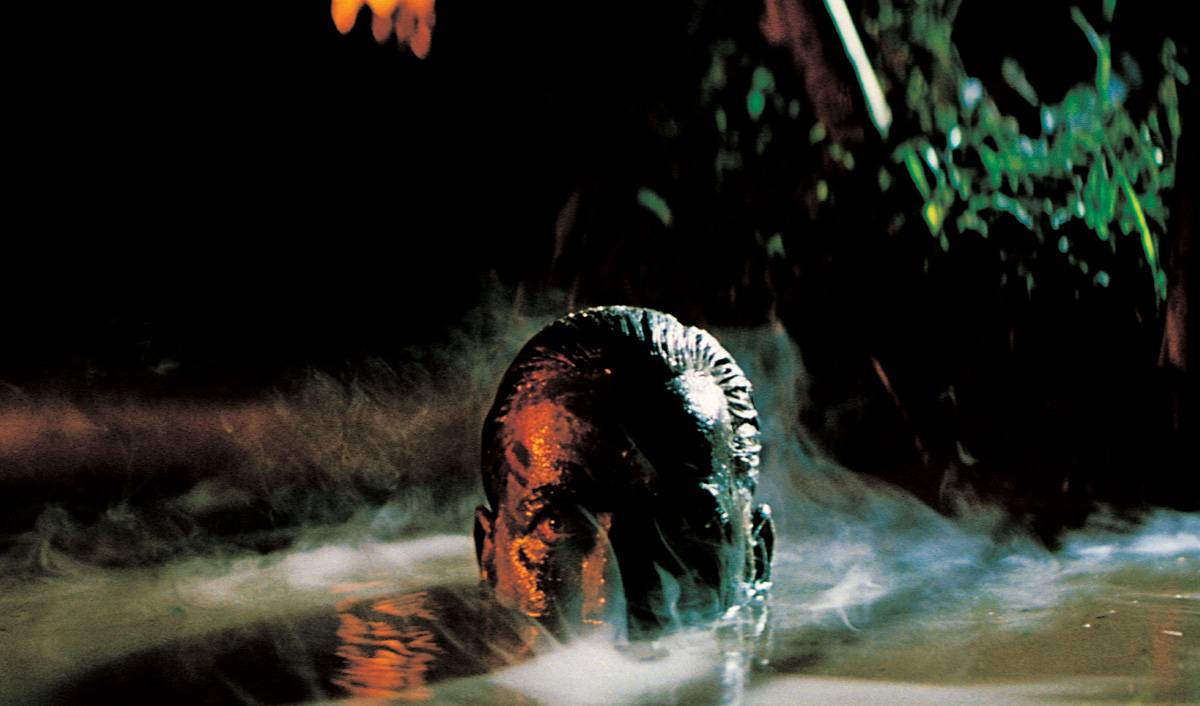

11. Stalker (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1979)

While many directors have been influential through their oeuvre, very few of them have been instrumental in the development of a cinematic theory, one that tries to find the philosophical, emotional and spiritual nature of cinema. One of such directors is Andrei Tarkovsky, a poet who sought to create films that went beyond what was expected of the medium, who tried to find the true voice of cinema, resulting in a short but flawless filmography that elevates cinema to the realm of the most spiritual art.

“Stalker” follows a group of men who wander into a restricted area known just as The Zone, a place where a meteorite crashed that is said to make the wishes of whoever goes in come true. They are guided by a stalker, a man who knows how to evade the authorities and the dangerous parts of the path in order to make it to The Zone.

Little can be said about “Stalker,” for it needs to be experienced in order to be understood. It is a poem about hope, faith, meaning, self-knowing. In the end, the film is not clear about the meaning of the story, in order to allow each viewer to have their own interpretation, their own intimate relationship with the story, so that real life can permeate the film and vice versa.

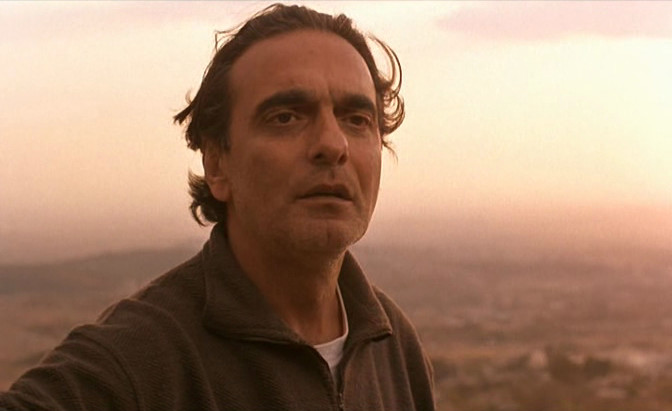

12. The Passenger (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1975)

Michelangelo Antonioni represented the voice of the disenchanted postwar Italians. After the raw representations of life in a destroyed country by neorealist directors like Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio De Sica, Antonioni portrayed a different Italy in his films, an Italy that was struggling to get back on its feet after the damages of the war, a country with deep emotional wounds that would change it forever.

In accordance to what the French philosophers called existentialism, Antonioni began making films about the vertigo of the future, about characters who couldn’t see themselves as a part of the world and thus looked for belonging in art, romance and adventure.

While the so-called existentialist trilogy (“L’Avventura,” “La Notte” and “L’Eclisse”) is more renowned and universally praised in Antonioni’s filmography, it is in “The Passenger,” starring Jack Nicholson, that the sense of existential dread and the desire to disappear into thin air is most patent.

It follows a reporter who, while in Africa, sees an opportunity to fake his death. The reporter uses this opportunity to leave his life and the everydayness of it, while vaguely involving himself in a gun-smuggling scheme. As the film goes on, the reporter’s ego begins to vanish, his fake death becoming a symbol for the frailty of identity. Antonioni created in this film a chilling portrait of a person who has given up on his life, but not on life itself.

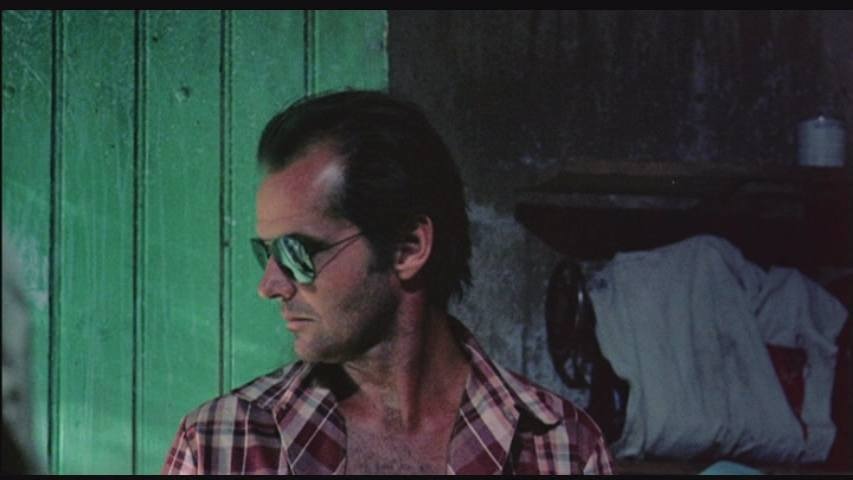

13. Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979)

The influence of the Nouvelle Vague ideology made it all the way to Hollywood. Some of the most influential and critically acclaimed American directors in recent history belong to a wave of filmmakers inspired by the iconoclastic ideals of directors like Godard, Truffaut and Varda.

This group, known as New Hollywood, included directors such as Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola, among others. Coppola, the creator of films like “The Godfather” and its sequels, was already well-established as a living legend when he set out to make “Apocalypse Now,” a descent into absolute madness based on a novel by Joseph Conrad.

The film takes place during the Vietnam War, and it follows Captain Willard, who receives the task of going deep into the jungle with the purpose to kill Colonel Kurtz, who has gone rogue and is now worshipped as a god by the locals. This is a war movie, but only in appearance; the war is only circumstantial, for the real interest of the film is Willard’s psychological and spiritual journey as he immerses himself in the derangement and utter insanity that war unleashes in the minds of soldiers.

The final encounter with Kurtz, the questioning of every personal and social truth, the destruction of the line that separates derangement from genius, the moment when the logic of every day is obliterated leaving only poetry behind, is a moment of profound mysticism that will be hard to forget or ignore.

14. Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976)

American cinema wouldn’t be the same without the input of Martin Scorsese. He revolutionized the action genre and perfected storytelling in Hollywood, elevating the overall quality of commercial films.

While his latest films feel more like exercises in style that focus on the flawless execution of camerawork and storytelling devices, leaving the intellectual explorations in the background, in the 1960s, together with screenwriter Paul Schrader, he made a work of art that deserves a place next to Camus’ “The Stranger” and Dostoyevsky’s “Crime and Punishment.”

The influence from French existentialist literature is undeniable in “Taxi Driver,” a tale about Travis Bickle, a Vietnam veteran who resorts to violence when he can’t understand the filth and the moral barrenness of the contemporary American city.

According to Schrader, when an European existential hero is faced with the meaninglessness of existence, they understand their pain and wish to kill themselves, while an American existential hero faced with the same situation doesn’t understand their pain and wish to kill other people.

If in “Apocalypse Now” we witnessed the landscape of madness and nonsense that is war, in “Taxi Driver” we see what happens when somebody who has been subject to such experiences tries to go back into society. The film has many readings and many interpretations for Travis’ character and his motivations; it doesn’t try to psychoanalyze him in order to allow the audience to decide what kind of person he is and what his actions mean.

15. El Topo (Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1970)

“El Topo,” one of the key films of the 1970s, is a twisted western in which we see the spiritual path a man has to take in order to earn the love of a woman. El Topo, played by Jodorowsky himself, rides a spiral path in the desert with the purpose of defeating the four masters of the revolver.

Each confrontation makes him think in new ways, and the spiritual preparation quickly becomes more important than the physical one. When his journey is over, El Topo is betrayed, and wakes up years later only to find himself worshipped by a colony of people with genetic abnormalities – cast out from society – living in the bottom of a cave.

Jodorowsky consecrated himself as one of the most significant underground filmmakers of the 70s, for his films were really weird, filled with bizarre imagery and cruel violence. This weirdness is contrasted with an abundance of symbols, allegories, and esoteric functions and rituals that give his films a metaphorical dimension, one so personal and intimate that the act of decoding them becomes an essential part of the viewing experience.

“El Topo” is in deep contact with the subconscious mind, and its images remain in the mind of those who see it for a long time, acquiring new meanings that enrich both the experience of the film and the lives of those who see it.

Author Bio: Elías García-Smith is a drifter, if you don’t see him wandering around New York City or Mexico City, he is probably watching a movie somewhere. His love for cinema started when he saw Jodorowsky’s ‘El Topo’ as a child, and he hasn’t stopped watching movies since then. He spends his spare time dreaming about the films he would like to make.