The independent cinema of today is very different from that of previous decades. As more complex narratives move to TV and streaming, smart studio fare for mature audiences has largely disappeared. In its place is indie cinema, which is now as much a term for films that don’t involve superheroes or explosions as it is for low-fi, experimental, no-budget movies.

To put it this way, in the first fifteen years of its existence, the top prizes of the Independent Spirit Awards and the Oscars only overlapped once. In the last ten years, the same film has won both awards five times. In some ways, indie cinema has become the adult of Hollywood filmmaking.

Which brings us to 2018 and an indie film paradox of sorts. On one hand, independent cinema is more mainstream than ever. On the other hand, even the most successful and well-known indies of the year were fiercely idiosyncratic, brilliantly made, and utterly unconcerned with the Hollywood mold. This list is here to celebrate that fact by counting down the ten best indies of 2018.

First, however, are some caveats. This list does not include documentaries or foreign films, even though they almost always function as indies in western markets. These genres are so expansive, and there have been so many exciting entries in both that they warrant their own lists. Second, this list looked at films made under the contemporary indie model. Budgets, casts, and publicity for these films have been larger than what past audiences would expect from an “artsy” film. That said, every film on this list fits the criteria of being independently made, both in terms of production and artistry.

10. Lean On Pete

Lean On Pete debuted at the 2017 Venice Film Festival to respectful reviews, but it was overshadowed by the Oscar contenders in the line-up. Being a 2017 film released in 2018 doesn’t look good, and Lean On Pete was released to little fanfare. It deserved better.

Directed by Andrew Haigh, who has steadily built a reputation as a nuanced, unshowy chronicler of hidden emotion, Lean On Pete presents a story about adversity, companionship, and poverty that never overreaches or tries to manipulate its audience. It manages to be straightforward without sacrificing tension, and every emotional beat feels earned.

Lean on Pete focuses on Charley, a teenager living an itinerate lifestyle with a father who is little more than well-meaning. Charley (played by Charlie Plummer) gets a job looking after a racehorse on its last legs and ends up on journey that manages to speak to the innate animal need for love while functioning as a travelogue of overlooked American landscapes and a reminder of how easy it is for anyone to sink into poverty.

Aside from Haigh’s direction and screenplay adapted from a book by Willy Vlautin, Lean On Pete works in large part because of its cast. Plummer carries the film with a sense of earnestness and determination that never feels cloying, while supporting turns from Steve Buscemi and Chloe Sevigny, among others, feel lived in and authentic.

9. A Private War

The trope of the combat journalist addicted to danger is so cliché that A Private War shouldn’t work. Somehow, the fact that it’s based on a true story only makes it seem more unoriginal. Yet, A Private War does more than just work. It tells a story that is urgent and moving.

A big part of this is because the real-life inspiration is so fascinating. Marie Colvin was one of the great combat journalists of her time. Her career spanned some of the worst conflicts of the 1980s and 90s. Her death in Syria is the kind of event lesser films would milk for maximum effect. Colvin defied the Syrian government’s ban on foreign journalists, and some believe that she was targeted by the Assad regime.

Another reason the film succeeds is because of lead Rosamund Pike. Pike plays Colvin as more than the one-note thrill seeker common in films that rely on real-world events to generate clout and publicity. The real-life Colvin was a cinematic figure, sporting an eyepatch and hopping from warzone to warzone, but Pike conveys the determination and empathy that made Colvin’s work so important.

Finally, Matthew Heineman’s direction elevates the film. A Private War is Heineman’s first narrative film. Heineman’s previous films, Cartel Land and City of Ghosts, are two of the most immersive, eye-opening documentaries of the decade. As a dramatic director, Heineman brings his own knowledge of combat reportage to the screen. Backed by Robert Richardson’s strong cinematography, A Private War is essential viewing for our times—an examination of geopolitics, journalism, and morality in a globalized world.

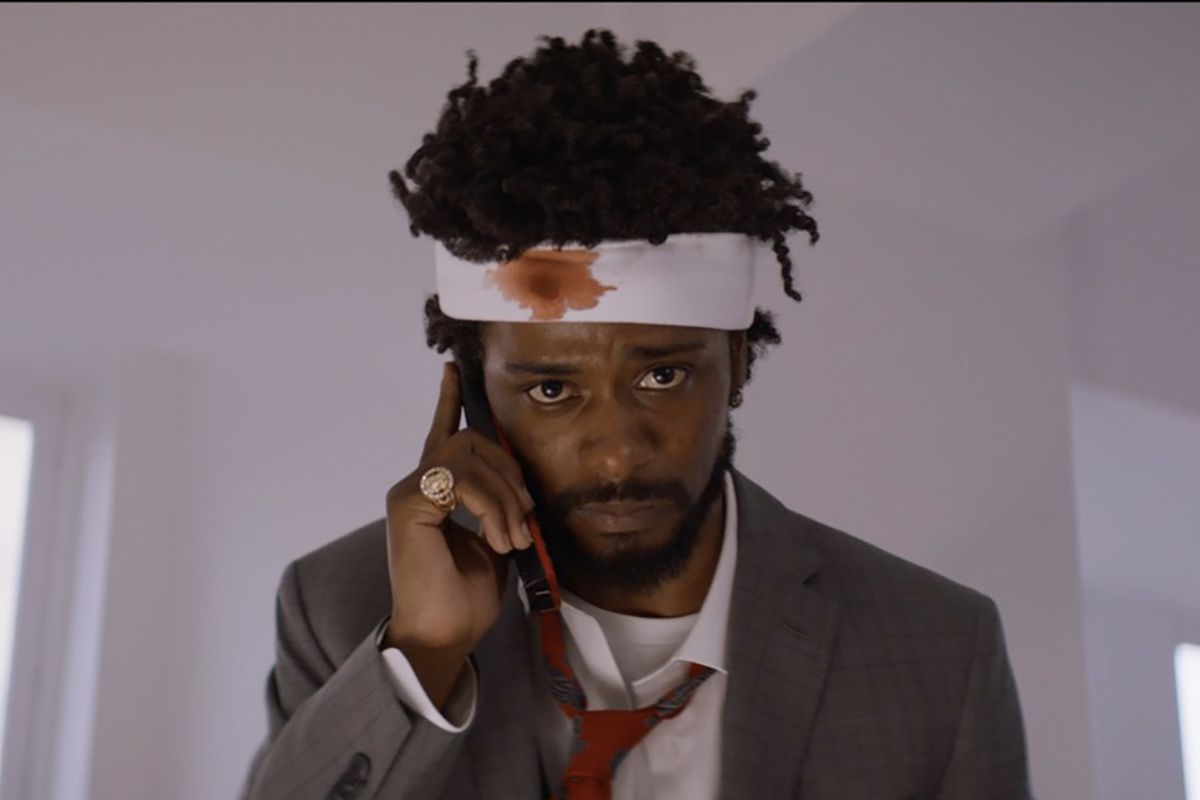

8. Sorry to Bother You

Few films could lay claim to the title of “Most Bonkers Film of 2018” as well as Sorry to Bother You. Some films are independent because they’re made with small casts or small budgets, and some films go further by gilding each scene with idiosyncrasy and insight until every beat feels new and different. That’s Sorry to Bother You.

The film is ostensibly the story of a young man caught between climbing an ethically bankrupt corporate ladder or fighting for a better world in solidarity with his co-workers. Within this premise, Sorry to Bother You manages to discuss race relations, income inequality, the pressures of being a young black professional in an economy that is color-blind and racist, and workers’ rights without ever feeling false or opportunistic.

Sorry to Bother You is the debut feature of musician and activist Boots Riley, who set the film in his native Oakland. It’s to Riley’s credit that Sorry to Bother You feels firmly set in our time, complete with all the problems and issues that entails, while telling a story that is so out there it practically exists in its own university. He’s also cobbled together one of the best ensembles of the year.

But perhaps the strongest aspect of Sorry to Bother You is the way it seamlessly incorporates surrealist flourishes—the white voice, telemarketers dropping into their callers’ homes—into a contemporary (and timely) story. Not since Being John Malcovich has a film been so confidently wacky that audiences and the industry couldn’t help but take it seriously.

7. Hereditary

Hereditary is one of a few debut films on this list, but few debuts are as assured as Ari Aster’s Sundance breakout. Sundance has become known as the place where one prestige horror film gets a jump on the year (for example, Get Out and The Witch), but Hereditary delivered the goods by being both exceptionally well-made and genuinely scary. Sometimes horror films sacrifice scares for prestige or vice versa. That is not the case here.

Part of Hereditary’s success is in the way that it focuses first and foremost on being an effective scare. It’s a welcome surprise that it’s such a well-acted depiction of grief, guilt, and family, and these emotional beats only up the tension. As the young girl who is initially at the center of the story, Milly Shapiro manages to be so off-putting that early audiences balked. Supporting turns from Ann Dowd and Gabriel Byrne are dutiful in roles that are requisite for horror, but each manages to craft a person out of a trope.

However, credit must go to Toni Collette and Alex Wolff playing a mother and son increasingly at odds but on a collision course. Wolff plays his character as a paranoid bomb of puberty and dread, his body and face struggling to contain an insurmountable horror he can only barely recognize. But it’s Collette, in a role that serves as a twisted companion to her breakout in The Sixth Sense, that drives Hereditary. Her sadness and anger resonate so strongly that her performance lingers as much as the headless and headbanging horror imagery.

6. If Beale Street Could Talk

Barry Jenkins could be forgiven for sweating his follow-up to Moonlight. His second film won the best picture Oscar and established Jenkins as an auteur-on-the-rise, so expectations post-Moonlight were sky high, and it’s not uncommon for director’s to choke against such lofty anticipation.

Yet with his third feature, If Beale Street Could Talk, Jenkins has shown himself to be an independent filmmaker in the truest sense: he tells often ignored stories with a voice that is both unique and informed by his influences. Beale Street, which Jenkins started on before Moonlight, is based on the James Baldwin novel and tells a story that is unfortunately still relevant.

Fonny and Tish are lifelong friends and lovers whose life together is destroyed when Fonny is accused (falsely) of a crime. Newcomer Kiki Layne and rising star Stephan James (Race, Homecoming) play the young couple, but Jenkins fills every frame with images and sounds that drive home the love and agony that defines the characters’ world.

Cinematographer James Laxton uses closeups to bring the audience into the characters’ souls, and actors like Brian Tyree Henry and Dave Franco pop in to deliver sometimes heart-breaking and sometimes curious commentary on the nature of love and society. While some viewers felt jolted out of the narrative by some of these cameos and Jenkins stylistic flourishes, the film onscreen is a beautifully told story inspired by an important voice and visualized by one of the most exciting filmmakers alive.