5. Hunger

It is the rare film that transforms fecal matter smeared on a prison cell into a stunning work of art, but that’s why we have British filmmaker and artist Steve McQueen. Hunger, McQueen’s debut, follows IRA member Bobby Sands (Michael Fassbender) as he leads a hunger strike in the infamous Maze prison in Northern Ireland in order to regain political prisoner status.

It is no surprise that this is the film that put both McQueen and Fassbender on the map. So much of the film is told through visuals that are beautiful and revolting like the aforementioned feces as well as snowflakes falling on a prison guards bloody knuckles.

It is only when Sands gets a visit from his childhood priest Father Dominic Moran (Liam Cunningham) that a substantial dialogue scene occurs. And what a conversation it is! The first 17 minutes are filmed in one uninterrupted wide shot of the two men as they debate the morality of a hunger strike where the men are destined to die.

When Sands is first brought into the prison he looks like a caveman with long, stringy hair and beard. Fassbender is unrecognizable until he’s had a prison-ordained haircut and beating. Leading up to the scene with Father Moran, we see him mostly acting and organizing without getting a sense of the man.

When he does speak, we see a man burdened by his own natural leadership but determined to do what is necessary. Hunger is a film about one man’s will to transform his body into a political weapon and the awesome power inherent in such an act.

4. In The Mood for Love

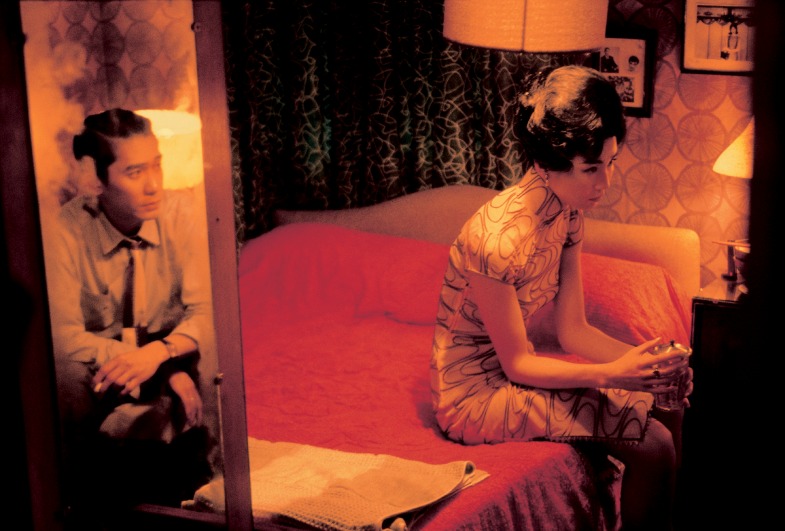

Only Wong Kar-wai could make one of the most erotic and sensual films in the history of cinema without the two leads ever even kissing. So much of In the Mood for Love’s power comes from the overwhelming desire and the inability to act upon it. Kar-wai’s lavish use of colors and slow-motion illicit the same sense of heightened sensuality that plagues our two protagonist as they deny their urges.

The film takes place in Hong Kong in 1962 and tracks the platonic love affair of a husband (Tony Leung) and wife (Maggie Cheung) from two separate marriages. Neighbors in the same apartment building, the two keep running into each other, slowly developing a pleasant, but not terribly deep friendship.

Over the course of the story, both come to realize that their respective spouses are engaged in their own affair with each other. Although the two feel an undeniable pull towards each other, they choose to not stoop to the same level as their partners.

It is no surprise that Leung and Cheung are two of Hong Kong’s biggest stars and their sad chemistry crackles off the screen. Kar-wai brings the two so close it’s almost unbearable. What’s so heartbreaking that the fact that the two never give in is exactly what makes you, the viewer, fall in love with them even more. A soulful and sexy treatise on love and desire. You will certain feel the title after watching this one.

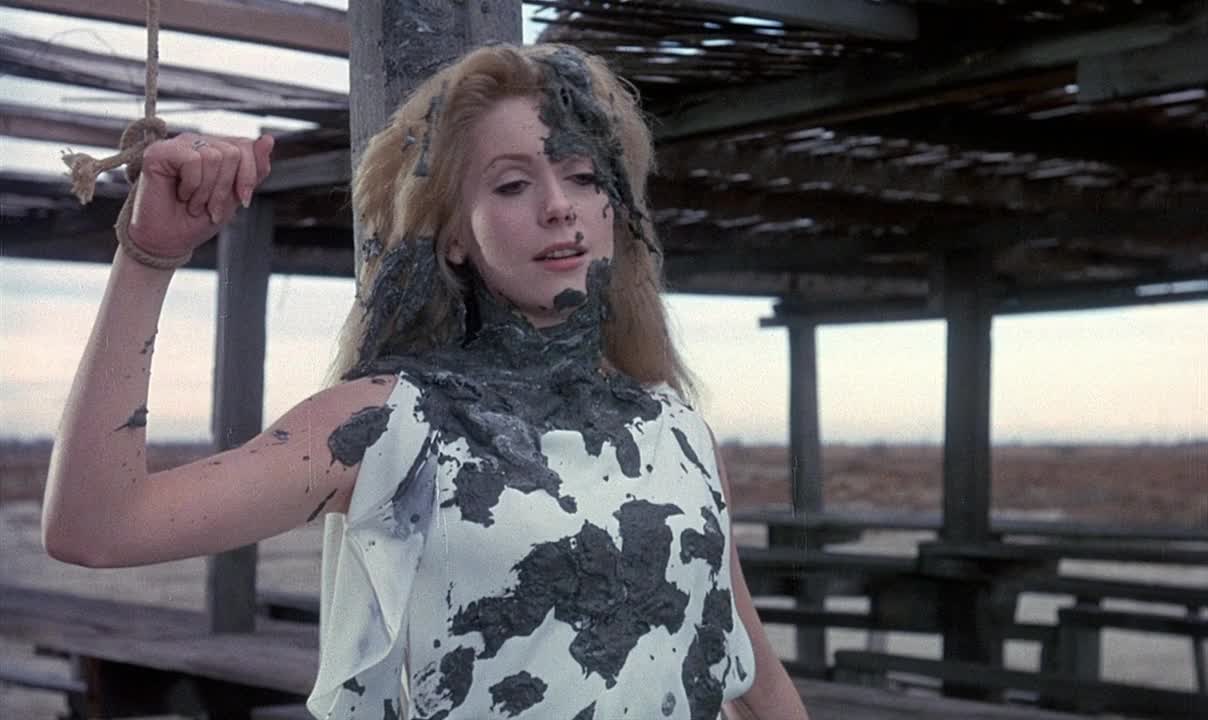

3. Belle de Jour

Upon its release in 1967, Belle de Jour was met with fascination and controversy. No film up to that time had dealt so frankly with female sexuality not to mention in such a bizarre, surreal and funny manner. Although Catherine Deneuve has said the experience of making the film was not a happy one, director Luis Bunuel deserves kudos for bringing to the screen a truly dazzling exploration of female desire and fantasy.

On paper, Severine Serizy (Deneuve) has the ideal life. She’s married to a handsome, successful doctor who loves and respects her. Despite this, Severine is unable to become aroused in the bedroom, hiding her S&M fantasizes from Pierre. Hearing about an upscale brothel, Severine begins secretly spending her days as a prostitute where she lives out her erotic desires.

At first, things seem to improve between her and Pierre, finally able to consummate their love but soon enough, one of her more obsessed clients, Marcel shows up at her door and her two lives begin to crash violently into each other.

The film is both sexy and scathing in its depiction of a bourgeoise housewife having to suppress her wants and desires to fulfill her obligations. Even more transgressive is the way Bunuel makes the fantasies and reality more indistinguishable as Severine progresses deeper into her new life as the titular Belle de Jour. There is no moral posturing and, if anything, Bunuel sides with Severine, showing the men in the film to be repressive, violent, or just plain oblivious to what she really wants.

2. Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters

Japanese writer Yukio Mishima has been a controversial writer even before he staged a coup against his country’s military and subsequent seppuku (ritual suicide). His writings often dealt with the conflict between mental repression and physical desires. So it comes as no surprise that Paul Schrader’s exhilarating and powerful biopic would be met with hostility from Mishima’s homeland of Japan.

The film tracks Mishima from a weak, sickly child into adulthood, transforming himself into a literary superstar fascinated with bodybuilding and the samurai code of honor. Schrader depicts the notorious writer as a closeted homosexual, obsessed from a young age with both the male form as well a the idea of death.

What makes the film so unique is the way it intersperses Mishima’s life with short adaptations of his work (The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, Kyoko’s House and Runaway Horses), all of which help examine the man’s internal struggles between thought and action . As Mishima says in narration, “The more I wrote, the more I realized mere words were not enough. So I found another form of expression.”

The film’s finale is a harrowing recreation of Mishima and his private army of devoted young men taking a Japanese general hostage while Mishima gives a speech in an attempt to have them join him in reinstating the Emperor as supreme ruler.

The scene is oddly heartbreaking as the writer’s impassioned words fall on the deaf or ridiculing ears of the Japanese Army. Mishima is a truly beautiful and humanist portrayal of a man at odds with his society, his sexuality and himself.

1. Diary of a Country Priest

So much of Robert Bresson’s films are obsessed with the intersection of the physical and the spiritual. Diary is perhaps his purest iteration of this conflict. The film follows a young priest newly assigned to a parish. He is an odd one, so completely dedicated to his ascetic lifestyle. He eats only bread and drinks only wine. The town takes an immediate disliking to him, his students playing pranks on him while the locals see him as cold and distant. The film is so self enclosed within the community that you get the feeling like the whole world is just as cruel and uncaring.

Much like Bresson’s later film Au Hasard Balthazar, despite such a negative view of humanity, the film and the main character achieves a kind of grace by the end but not without a worldly price. Diary is a stripped-down film, free of so many conventions that are common in most films.

Most obvious is Bresson’s uses of non-actors, including Claude Laydu as the films protagonist. Laydu’s performance is a revelation. Quiet and understated, he conveys a man of the cloth racked with an internal guilt, striving to reach a beatific state.

Bresson’s brilliant filmmaking techniques and use of Laydu’s voice-over to contrast what we see on the screen only elevates his star’s work. The filmmaker’s style is often labeled austere but Diary’s underlying emotion and the struggle of its protagonist are overwhelmingly palpable.

One feels the same sense of spiritual imprisonment that Laydu feels until the rousing finale. There’s a reason Bresson is so adored by the likes of Bergman and Tarkovsky, he utterly transcends the cinematic form.

Author Bio: Ed Leer is a writer and filmmaker based out of Los Angeles. In addition to Taste of Cinema, he is a culture writer for CounterPunch Magazine.