5. The Handmaiden (Park Chan-wook, 2016)

Chan-wook’s films often function like puzzles, and The Handmaiden is no exception. Adapted from the novel Fingersmith by Sarah Walters, the British Victorian setting of its source is transplanted to Korea during Japanese rule.

This is a smart move, using the complicated plot of Korean handmaiden who tries to trick a Japanese woman into marrying a conman as a way of commenting on the prickly relationship between both countries at the time. This is complicated by the sexual relationship that develops between the two women, creating a complex web of psychosexual intrigue that doesn’t let up until the final enigmatic scene.

Told in three parts and from three rather different perspectives, The Handmaiden can be a somewhat difficult film to follow (although not nearly as complex as Chan-wook’s recent TV series, the baffling The Little Drummer Girl). Once you get into its rhythms however, it is a deeply satisfying watch, showing the director to be one of the most visually inventive in the business.

4. Gone Girl (David Fincher, 2014)

Possibly David Fincher’s best film, Gone Girl is a masterpiece of misdirection. Based on the best-selling novel by Gillian Flynn, who has now gone on to be one of the most in-demand screenwriters in Hollywood, Gone Girl stars Ben Affleck as a writing teacher who comes home to find his wife is missing.

Told via a variety of flashbacks, Gone Girl is best known for the remarkable plot-twist that happens around halfway through the story. Prompting a deluge of think pieces upon its release, Gone Girl asks if we can ever truly know the person that we are married to.

As visually entertaining as it is morally complex, Gone Girl is one of the best explorations of traditional gender roles to come out of Hollywood in the past ten years, the kind of adult drama that critics claim they simply don’t make anymore. David Fincher’s methodically cool and glacial approach was the perfect match with Flynn’s spiky and inquisitive screenplay; asking key questions about how we pretend to be something we’re not when going into a relationship.

3. Notorious (Alfred Hitchcock, 1946)

Alfred Hitchcock was the master of the romantic thriller, a man fascinated by women, specifically blondes, and channeled that fascination into some of his best films. Notorious is one of his most lusciously romantic films, a combination of the spy thriller and the film noir that showed that the previously mechanical director had a lot of heart after all.

It stars Cary Grant as a government agent attempting to infiltrate a ring of Nazis in Brazil during the immediate aftermath of WW2. To help him with his efforts, he enlists the help of Alicia Huberman, played by Ingrid Bergman in one of her best roles, the daughter of a disgraced American Nazi spy.

As Hitchcock famously told Truffaut, the main conflict of the film is between love and duty, a morally complex web of deceit and illusion. The film is famous for its two-and-a-half-minute kiss that got around the rules of the Hays Code by making the couple only lock lips for three seconds at a time.

2. Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944)

The film noir genre that sprung up in the USA during the 1940s was essential in crafting the concept of the romantic thriller. Double Indemnity, based on the novella by James M.Cain, and co-written with Raymond Chandler, is often considered the archetypal film of the genre.

Starring Fred MacMurray as an insurance agent named Neff who is convinced by a desperate housewife to commit murder in order to release a significant financial payout, Double Indemnity is characterised by its cynical, adult tone, whipsmart dialogue, flashback structure and claustrophobic low-angle framing.

This utter cynicism was a new step for Hollywood, especially in the methodical way the two protagonists plot out the central murder. As it keeps one guessing about the true motives of both characters throughout, Double Indemnity’s view of human nature is a lowly one: men and women alike are only out for themselves yet still beholden to their most base natures. While 40s movies still couldn’t show sex explicitly, it’s obvious that Neff is motivated by lust, setting a template for the romantic thriller that persists until this day.

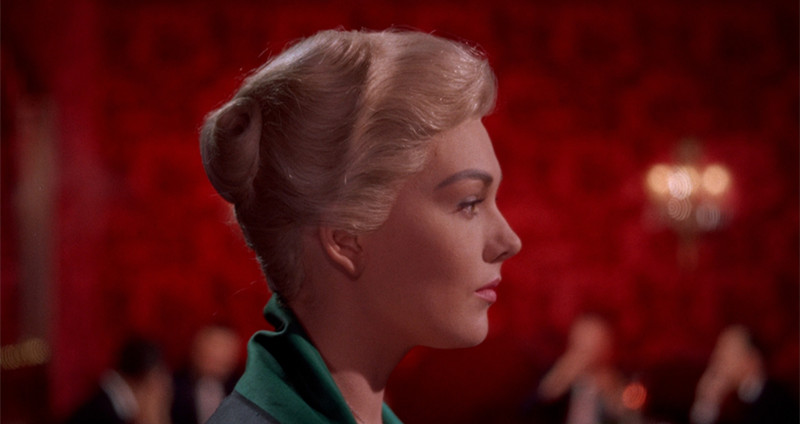

1. Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958)

Vertigo was voted by critics in the 2012 Sight and Sound Poll as the greatest film of all time, and with good reason. It’s a deliriously intoxicating tale of love that is perhaps as perfectly constructed as any film could wish to be.

Adapted from the French novel From Among the Dead, it stars James Stewart as a police officer with a fear of heights who falls for a mysterious blonde woman, played by Kim Novak. But soon he finds out that things are not as they initially seem, leading to a dazzling tale of deceit that keeps the viewer guessing right up until the final scene.

So elegant in its narrative construction that it can only be fully explained with repeat viewings, Vertigo saw Alfred Hitchcock at the height of his filmmaking powers. For example, it was the first film that used the dolly zoom, an in-camera effect that creates a subjective feeling of disorientation, now known as “the Vertigo effect”.