5. Grave of the Fireflies

It was the late 80s and Studio Ghibli was still just a lowly Japanese company with just a couple of animated films to its name. Still in its infancy, few would have expected such a drastic departure from Miyazaki’s fantastical stories that had that brought success early on. Fortunately, Ghibli likes taking chances and so Isao Takahata brought to the big screen one of the saddest films ever made, in Grave of the Fireflies.

The tragic story takes place in Japan during the end of the Second World War and follows a boy named Seita and his young sister Setsuko as they try to survive. The vicious image of a war-ridden nation is perfectly juxtaposed by the innocence of the main protagonists.

Seita suffers by the loss of his mother, is abused and taken advantage of but still strives to carry on to protect his sister. Under different circumstances, Grave of the Fireflies could have been a heroic story about the perseverance of the human spirit.

Alas, little Setsuko dies of starvation with her big brother forced to cremate her and go on alone. He meets the same unjust fate a few weeks later dying of malnutrition on a railway station. The bleak ending drives home the film’s anti-war message and elicits deep and powerful emotions from its audience.

4. The Mist

Frank Darabont’s third adaptation of a Stephen King novel starts unsurprisingly enough as most of the popular author’s horror novels. Without any explanation, a sudden surge of monsters overwhelms the citizens of a small town. The mist covering the town sets the tone for a mysterious atmosphere and a lot of suspense. As the story moves along, the film keeps following a formulaic route and nothing can prepare you for the unexpectedly grim conclusion.

Darabont was not satisfied with King’s ending so he wrote his own. As David drives in the mist with his son and three survivors, the car runs out of gas. The rumble is getting closer and in an act of mercy, David uses the four bullets he has left to kill the others and spare them from the terrible fate about to befall them.

Thomas Jane’s uneven performance may take something out of the horrifying scene of a man having to murder his own son but the real tragedy comes moments later, as a group of soldiers and a truck full of survivors emerges from the mist in a scene that can be used as the definition or tragic irony.

King may have loved this new ending but one thing is for certain; the Mist’s abrupt turn to nihilism will shock and haunt you for a long time.

3. Chinatown

“Forget it Jake. It’s Chinatown.”

The impact of these words still echoes in old theatres as one of the bleakest lines ever uttered. Polanski’s neo-noir masterpiece is a welter of corruption, violence and perversion. When private investigator Jake Gittes is hired to follow the chief engineer for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, he stumbles into major conspiracy with multiple layers of deceit.

Death lurks in every corner of Chinatown and the final reveal of Evelyn’s daughter Katherine being also her sister, as a result of being raped by her father at the age of 15, is a devastating blow to viewers. Alas, this twisted tale of monstrosity is far from over. When the two women attempt to flee, Evelyn is killed, leaving Katherine in the hands of the villainous Cross. With the authorities in his pocket, nothing can be done to bring justice to the world of Chinatown.

The final line is an acknowledgment of the resignation felt by the characters. In life there is no divine intervention. If you are powerful enough, right and wrong are but blurry lines to be traversed at will without consequences. It’s Chinatown.

2. The Boy in the Striped Pajamas

WWII films can be the source of great drama and Mark Herman’s The Boy in the Striped Pajamas fully takes advantages of this. The story follows Bruno, the eight-year-old son of the commandant at a German concentration camp, and Shmuel a Jewish boy imprisoned there. Two very different aspects of upbringing collide in a beautiful friendship viewed through the prism of childhood innocence, with Bruno trying to understand the situation while helping his new friend.

The grim setting of the concentration camp contrasts with the lavish image of the commandant’s residence to accentuate the slow convergence of the two main characters. They realize that their differences are only circumstantial and although they can’t fully comprehend it, they feel the injustice inflicted on the world.

The story lends itself for a dark ending which comes when Bruno sneaks in the camp to be with Shmuel. The children, along with hundreds of people are shoved in a room and stripped naked. The gas starts flowing from the ceiling and audiences are left in despair at the appalling events that took place during one of the most shameful periods in world history.

1. Requiem for a Dream

If there was ever a film made with the sole purpose of depressing an audience, it’s Darren Aronofsky’s very aptly titled Requiem for a Dream. A tale of sorrow through and through, following the lives of four people as they spiral out of control. Drug addiction takes center stage as the protagonists try to achieve dreams of fame and wealth but are sucked into a black hole of suffering.

The montage at the end is one of true torment as all four main characters slowly crouch into a fetal position under Clint Mansell’s magnificently melancholic Lux Aeterna. Tyrone ends up in prison and suffering from withdrawal. Harry gets his hand amputated from intravenous drug abuse.

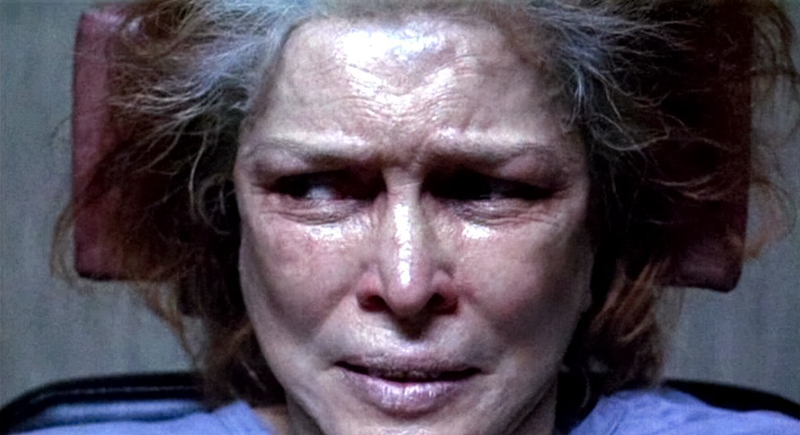

Sara, addicted to meth and severly hallucinating, undergoes electroshock therapy. Marion ends up in prostitution to satisfy her heroine habit. There is no redemption to be had. No glimmer of hope remaining. Aronofsky’s world is one of utter decimation and the protagonists pay the highest price for their mistakes.