When an image of a film that’s inherently embedded with the culture of the Royal Kingdom comes to mind, especially to the uninformed, a scene involving pompous aristocrats sipping tea and eating biscuits, speaking in exaggerated cockney accents is to be expected. However, the reality of a British film is far more complex than that stereotypical depiction.

Since its peak back in the 50s with its Realist films, British Cinema has always been concerned with realistically depicting rebellion. While their counterparts of the Nouvelle Vague were most concerned with stylizing similar subject matters, British filmmakers immersed themselves with more honest depictions of dissent.

The films on this list, through a myriad of different approaches, tackle the inherent concept of this sense of subversion, be it through their intriguing narratives or even the very filmmaking behind the films themselves. Without further ado, these are the 10 most British films of all time.

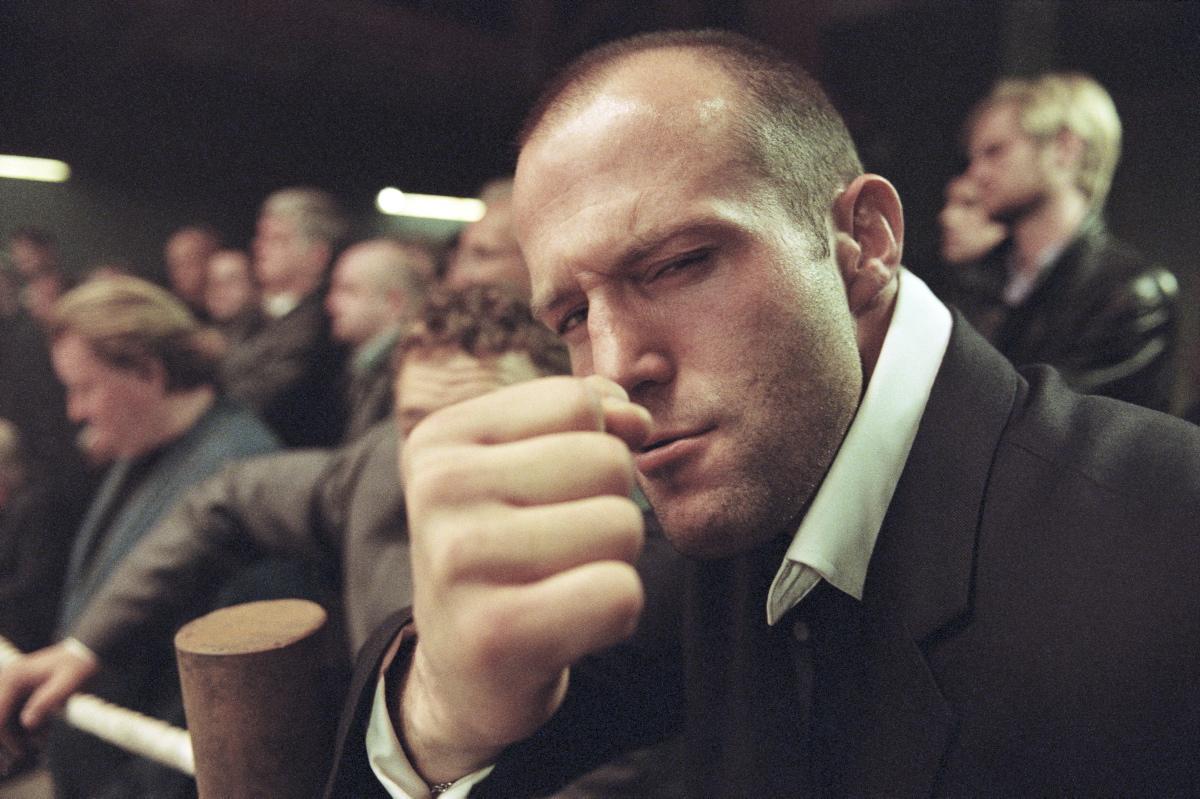

10. This is England

Though the portrayal of marginalised delinquency isn’t a concept brand new to the world of film, and it certainly comes across as stale when put in context of American Coming-of-Age, we should never underestimate the capabilities of British filmmakers. Especially within the genre that thrusted them to the forefront of world cinema half a century prior.

This is England offers a brilliant and gritty portrait of a story we’ve all heard before a million times in film. The story of an angsty teen coming of age. What truly sets this film apart, beyond the cultural element it blatantly exudes, is character perspective. Looking past the cinema-verite visual style, the selection of shots truly contributed a lot in building a perspective. One that adds order to the apparent chaos. Sense to the senseless. Empathy to the cliche.

And let’s not forget how natural everything flows. The characters seem like real people. The story, regardless of its banality, feel like an actual experience. Everything feels so real and well directed that you just forget that you’re watching an actual film (save for the few moments where the cheesy soundtrack breaks the suspension of disbelief) but instead, peering through a window into the lives of these characters.

This is England feels and flows like The 400 Blows and it certainly pays homage to it with the beach scenes. It’s ugly but it comes with honesty and if you truly wish to understand the incomprehensible nature of skinhead culture, brace yourself for this powerful examination of rebellion.

9. Hot Fuzz

A much more light-hearted entry on this list, Edgar Wright’s comedic masterpiece Hot Fuzz takes the stern genre of police procedural and crafts an insanely fun buddy cop chock-filled with laughter and action from start to finish.

Don’t let the seemingly generic surface of its narrative fool you, Edgar Wright is nothing but a mediocre filmmaker. The film’s innate use of circular storytelling as well as hyperbolic representations of the British stereotype propelled the lackluster formula of the buddy cop genre to such great heights. Not only is this film a masterclass in comedy, but it is for pace. Like in his later “Baby Driver”}, Wright cuts his film like a musical, the sequence is so incredibly pleasing.

Hot Fuzz may not be a film that deserves a right to be studied in film school like the other entries on this list, it is important. It may not have revolutionized the genre of comedy, but its creative use of which as well as its timeless narrative certainly helped it earn its significance in the canon of film history.

8. I, Daniel Blake

One thing British cinema is incredible at is the representation of the underprivileged. Director Ken Loach’s second Palme D’or winning film explore the Kafkaesque concept of bureaucracy, examining the ironically overinflated process in a film that examines the struggles of the underprivileged in a stunningly painted realist portrait. One that doesn’t dare shy from the gritty details.

What’s exceptional about this contemporary masterpiece is the unpredictable nature of its plot. I, Daniel Blake is essentially a 100-minute long cacophony of these great moments. Moments stitched together with the addition of great characters. Characters that only serve the greater purpose of the bombastic narrative, but characters who offer a strong sense of realism, portraying the marginalized in unique and realistic ways.

I, Daniel Blake is a film for anyone. It raises thought-provoking ideals of the those we won’t even care to bat an eye for. There’s so much brilliant, heart-wrenching moments of the narrative to draw you in, but even more substance behind these moments to truly lose you in the honest, painful world it built.

7. A Clockwork Orange

Naming a director like Kubrick on any top list may just be an easy pick, but nevertheless, a fitting one on most occasions. Kubrick’s dystopian portrayal of youth gone astray truly made for an epic viewing. A film that examines society’s impact on the already disillusioned youth, set against the contrasting backdrop of a cockney-inspired pretentious world.

There’s not much to say about A Clockwork Orange that has not already been said in a million others lists. However, its greatness as not only a British film, or a Kubrick film, but a film in general should always be mentioned. It transformed what it was like to tell a story or even construct a character, held together by the vision of perhaps the greatest director to have ever lived.

The unique way the film represents its allegorical personification of youth may not be as honest as the other films on this entry, but it certainly is masterful. If film is a canvas, then surely Kubrick is the one constantly painting over what’s already drawn. A Clockwork Orange is an absolute powerhouse of a film that raises asks us “How much in too much” in a world built that has already far exceeded the threshold.

6. The Third Man

Much like Polanski’s Chinatown, Carol Reed’s The Third Man offers a relatively subversive interpretation of a genre already notorious for subversion, in an era where that particular class of film is still fresh and ever-relevant.

The Third Man starts and progresses not too unlike any other film noir of its time, sparing no expense in setting up a bleak and cynical world filled with a myriad of different plot devices and an increasingly complex plot that doesn’t quite capture audiences immediately, this time set against the expressionistic backdrop of a postwar Vienna. But something is different.

The world built by Reed in the film, despite being highly stylised, even for noir standards, seems so real and without glamour. The country is captured with such subjective cynicism, embedded with the style of the filmmaker, yet the world feels alive.

This strong eye of realism embellished in the minute details truly adds to the quality of the film, and coupled with the film’s exaggerated lighting, camera angles and editing, The Third Man seems so fresh and engaging. And let us not forget about Orson Welles. His presence is so commanding, so powerful, that every scene he’s in adds this uncanny air of brilliance to the increasingly engaging narrative. A narrative that progresses slowly and like any good noir, falls into its own sardonic place amidst a cacophony of tropes and conventions.

The Third Man is a mindful film. It’s mindful for the historical context behind the zeitgeist as well as the country it’s set against. It’s mindful of the genre and the conventions, however original they may see, that define it. And most importantly, it’s mindful for its audience and Reed uses this mastery over us to craft this powerful piece of filmmaking that defies style and genre and transcends time to earn its rightful place among the canon of film history.