Cinema is its own language. It’s a fact that has been examined and dissected for over one hundred years at this point. Subjectivity is also a finicky concept to deal with. Bad films generally do not connect with the use of filmmaking as a linguistic medium (an art form that can communicate with its own form of structures). Many good films – and classics – abide by these rules (or are capable of bringing something new to said rules). Again, subjectivity is a bit tricky.

There are great films that do not abide by the rules of cinema; what separates these from “bad” works, is the respective filmmaker’s knowledge of the cinematic language through-and-through, along with the ability to break away from it through wisdom and not neglect.

The term “freewheeling” is interesting when it applies to cinema. It does not simply mean “wacky”, “unorthodox”, or “uncontrolled”. It can mean all of these terms, but it represents its own echelon of uniqueness. There are some rule breakers here, and there are some eccentric rides as well.

These works are idiosyncratic; sometimes being different is all there is to it. Some of these works aren’t even primarily known for being against-the-norm, but all ten of these films work against the grain. Here are ten of the most freewheeling films in cinema history.

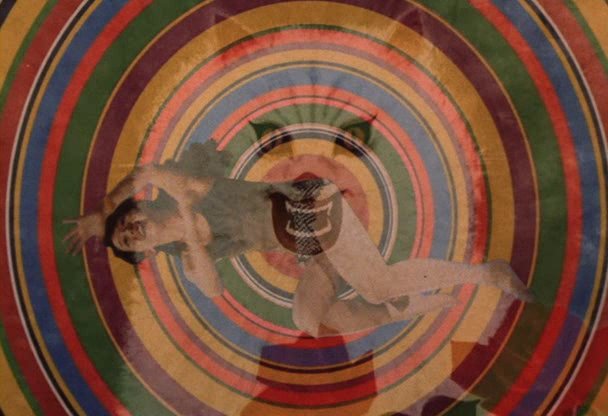

1. Daisies

If you’ve been reading specifically my articles lately (not entirely sure why you would), you have seen this Vera Chytilová title pop up often. Daisies is just so within its own universe, it’s hard to not include it on many lists, let alone a list that honours free thinking, free sprawling works.

Daisies – a feminist, new wave opus – defies more than cinema; it was built to spit in the faces of members of the oppressive elite. The dinner laid out for communist rulers is desecrated through feasting and toying.

The film starts with basic, monotone conversation that shifts into fifth gear rather quickly; clearly, higher powers are listening, and the film’s characters begin to no longer care what thought police are about. Yes, Daisies is so defiant, but its courage (towards political parties, societal tyrants, and the mainstream movie-going public) only gets more noticeable (and magnificent) with age.

2. The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie

One of Luis Buñuel’s final films, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie is based on the hell-bent idea that the acclaimed filmmaker could never shake off: what would it be like if the upper class had one of their rich feasts in hell? The entire film follows various socialites and aristocrats, as they try to pull off the simple act of having dinner. This dinner keeps getting postponed for a plethora of reasons, and each subsequent excuse gets more and more absurd.

The film dives into the subconscious, as storylines get cut short by characters waking up (only to find themselves a part of another dream). We’re no longer seeing a quest taking place, but a never-ending, sadistic torture instead. The attempts get shorter, scarier, weirder, and more violent. Our common nightmares have been brought to life, yet they are inflicted on other people. Do we laugh, or do we fear for them?

3. Holy Motors

One of the metaphysical greats of the new millennium, Leos Carax’s cinematic existential crisis Holy Motors is already one for the ages. An actor takes on “roles” for films that never seem like they are taking place.

The actor is performing, sure, but there aren’t really any sets, cameras, or crew members present to capture this work (save for some very debatable examples). He acts for us, as if he is trapped within our disc or streaming service. He doesn’t live in any filmmaking hub (especially not tinsel town), but rather in film as a whole. He dips through genres at ease, and experiences all the highs and lows of life.

Much of what happens makes very little sense to us, but it makes enough sense for the actor to make it all work. We see film represented as a universe rather than a craft, and we also see imagination being challenged in many ways.

4. House

Yes, how could we forget the Japanese neurotic horror comedy House? Have you ever tried to explain Nobuhiko Obayashi’s cult classic to unfamiliar filmgoers, and see how perplexed they may react? It’s just one of those films that was destined to be atrocious or brilliant.

For most people, it falls into the latter category. How do you even go into the film? Yes, a humble home has a fixation with eating the schoolgirls that visit it. Even the basic premise – the most straightforward part of the film – is insane when you think about it.

However, House dips into otherworldly elements in very niche ways. Animation, blue-screen, and other interesting effects are used in such bastardized ways; you’re pulled away from the film, but are still intrigued by what bizarre events are taking place. Basically, it’s House. You’re either speaking its language, or you’ll never understand it.

5. Inland Empire

Many cinephiles love David Lynch, and many of his works have been brought up onto pedestals in this new millennium (whether the works were recent, or old and reevaluated). I’m going out on a limb and proclaiming Inland Empire to be way too underrated if we’re going to be bringing up Lynch in daily conversations. It simply is not talked about enough, especially when it encompasses many of Lynch’s best tropes.

The film never really makes complete sense (more akin to Eraserhead, rather than an ambiguous Mulholland Drive); its three hour runtime and use of cheap, basic camcorders will drive you delirious enough to not have any proper answers after the first watch. The effects are so basic, yet Lynch’s understanding of how films work make even the silliest images beyond terrifying.

Laura Dern’s multifaceted, brauvera performance is a frightened mind personified. This metaphysical film features a character that becomes aware of her delusions (and even the shattering of the film around her), and it’s such captivating nausea.