5. Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959): Elle and Lui in the shower

The story of two simple people, and simultaneously a chronicle of two complicated worlds, the legendary film “Hiroshima Mon Amour” by Alain Resnais, one of the French New Wave’s most grim-stirring directors, eternally survives through its grasp on history’s putrid corpse and love’s blooming beauty.

She’s a French actress who’s in Japan for the purpose of an anti-war film. Perhaps Hiroshima’s nightmarish past seems distant and otherworldly, but she’s deeply aware of the war’s elusive greedy monster. He’s Japanese, hurt and influenced by Hiroshima’s foregone tragedy. They are both married, settled, and of solid stances. They are both in love with each other, in the impermanence of their present and through the intense temporary impact of their past.

Lovers share the same bed, heart, and body. But the long-suffering lovers of “Hiroshima Mon Amour” need to share the same catharsis. Stripped of materialistic covers and sentimental sorrows, they let themselves have one another in an act of remission. The water’s flow on their skin can carry all of the world’s sins and troubles away. They represent two different and at once identical spheres of a bleak reality. Yet, they have built a pure and graceful sphere of their own.

4. Pierrot le Fou (1965): A kiss from two cars

Arguably not proposed for beginners, and definitely one of the French New Wave’s most iconic films, “Pierrot le Fou” comes back to the present again and again through its unspoiled substance and undimmed charm. Projected on its characters’ morbid glory, on its heterodox strike with distressing norms and flowing emotions, and on its dazzling vintage beauty, Godard’s most intoxicating work will never be idealistically obsolete or humanely irrelevant.

“A story should have a beginning, a middle and an end, but not necessarily in that order,” Godard said one-on-one in words and various times through his pictures. “Pierrot le Fou” is a nonlinear film about Ferdinand and Marianne: a man repressed by the void space of nothingness, and a woman manipulated by both recorded and unrecorded societal norms. The two set off on a trip that aims to a conquest of liberty instead of a final destination. But leaving behind external links doesn’t lead to an inner exemption of personal demons.

She could never accept Ferdinand; she would never make a real effort to understand him. He could never accept himself and truly love her, either. But despite the chaotic gap that rises between them, there’s a strong force keeping them moving forward together. He’s in a red car and she’s in a blue one, but for a moment nothing can stop them from kissing.

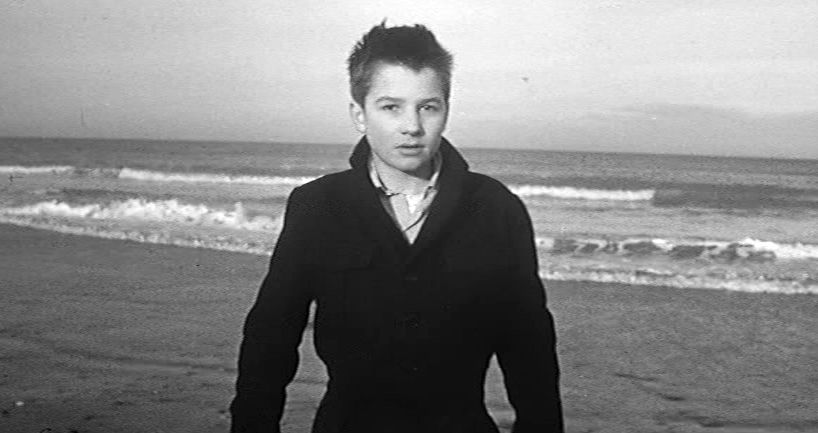

3. The 400 Blows (1959): The last scene at the beach

François Truffaut’s autobiographical film “Les Quatre Cents Coups” on a first level generates deep emotions of misery, whereas on a second level it gives rise to a hearty feeling of optimism and hope. Perhaps the story’s first notional level takes effect extensively, but the second level’s surface is completed and binds the film, vividly emerging in the quintessential last scene.

Antoine, Truffaut’s cinematic alter ego, suggests that even during a premature age, everything in life goes wrong: the financial adequacy, the parental care, and the social treatment can be at the same time dysfunctional. In a welter of misuse and criminal ignorance, what is the role of an unprotected child? This is the woeful question that Antoine’s existence screams silently.

Reality’s binds are hefty and sometimes unbearable. However, the heart of a child can be stronger than any material fetters. Antoine’s escape from his prison’s real and imaginary bars stands for Truffaut’s introduction to the liberating device of cinema by André Basin. That vast sea lying in front of Antoine is Truffaut’s future of purification and creativity. Cinema owes a lot to the legendary French film critic, but essentially, we all owe to him for having Truffaut and his “Les Quatre Cents Coups.”

2. Jules and Jim (1962): Running over the bridge

Exceeding the constraints of its era’s societal stereotypes, sexual taboos, and technical norms, François Truffaut’s “Jules et Jim” is a hardliner piece of the French New Wave, as with respect to its cinematic form, so in relation to its concepts and placements. Following the naturalistic transition from youth’s carefree years to the incumbencies of a mature age, this filmic experience is at once a delight and a wound.

Jules and Jim share the same bohemianism lifestyle, as well as the same perceptions on various generic and personal subjects. Their substantive friendship, which used to be expressed and satisfied through a series of libertarian common actions and decisions, would be gradually disordered by a woman. Catherine severely defines their lives, since she comprises a lot more than female company or a confirmation of an unbound personal status for both of them.

Their indistinct friable triangle survived for years until Jules married her, and their life for the first time resembles a realistic life’s gloomy pattern. Observing the psychological spectrums of the main characters unfolding and revealing all of their quality, as well as plenty real-life constituents and prospects, “Jules et Jim” finally becomes too real. The story’s turning point is captured in the scene of the three protagonists running over a bridge. Happy, spontaneous, and clueless, one day they would cross one of life’s deterministic bridges, never to come back.

1. Breathless (1960): “The last shot”

Since his first overbold endeavor to create a new cinematic code, Jean-Luc Godard has directed more than 100 films. Some of them are good, some of them are very good, whereas few of them are flawless from various points of view. Godard’s first feature film “À bout de soufflé” in 1960 certainly isn’t his best work, but it’s the first groundbreaking step that covered the chaotic gap between a former conceptual conventionality and obedience to long-lasting technical rules.

Turning the story’s hero into a character that used to be a film’s typical anti-hero, the legendary French director manages to remodel the foundation of a common societal apperception of multiform with unacceptable actions and personal externalizations. Of course, the film’s novelty regarding the technical parameters has influenced cinema and art in general. Yet, its semantic edginess reached art’s higher level by having the dynamics of bending a rusty and stiff conscience.

Michel, the story’s charming outlaw, is both a perpetrator and a victim. He steals cars and has even killed a police officer. Always with a cigarette stuck in his lips, he struggles to hide a part of him and share another. Perhaps he’s in love with Patricia; perhaps he isn’t. Howbeit, Patricia has always something to do and her path is always the opposite than Michel’s.

Nothing else was possible for Michel’s fate: he was meant to be killed, since in this story he’s the weak one. “When you photograph a face… you photograph the soul behind it,” Godard claims. This is what he did for the first time in this criminal’s troubled face and iconic moves. Yet, Patricia’s questing eyes as Michel leaves his last breath as a result of her actions reveal everything.