5. In the Mood for Love

Both subtle poetic and visually groundbreaking, Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love is an intricate story of romantic yearning and moving moments. With its aching musical soundtrack and exquisitely abstract cinematography by Christopher Doyle and Mark Lee Ping-bin, this film has secured a place in the cinematic canon, and is without doubt a landmark in Wong’s career.

In the Mood for Love opens in Hong Kong, 1962. Chow Mo-wan (Tony Leung Chiu-wai) and Su Li-zhen (Maggie Cheung Man-yuk) move into neighbouring apartments on the same day. Their encounters are brief, formal and polite – until a discovery about their spouses clandestine affair creates an intimate bond between them. To the soul stirring score of Yumeji’s Theme (created by Shigeru Umebayashi), Chow and Su night after night intersect at a diner.

Empathizing with each other’s feelings leads to a magnetic attraction, hinting at a budding romance, but given their clearly demarcated pathways and her reserved nature, the gap becomes insurmountable. Wong brews up a vividly coloured, highly atmospheric world in which every frame is brimful of life and yearning, of melancholy and beauty. As someone rightly said, it’s not the story so much as the way in which it is told that matters.

In the end, the uselessness of it all becomes evident to both and they surrender to the will of the universe, each going their separate ways. Instead of grieving, they take it in their stride and move on. Eventually, Ms. Chan will find the meaning of life in her child while Mr. Chow will go to Singapore. Yet they will carry with them the feelings they experienced somewhere in their hearts.

4. Rashomon

Rashomon is not just about an investigation to determine who is behind a crime. It’s not about guilt or innocence, instead, it focuses on something far more profound and thought-provoking – the inability of any one man to know the truth, no matter how clearly he thinks he has seen something. It is a story of how different perspectives can give different accounts of reality thus distorting the absolute truth.

The central tale, which tells of the rape of a woman (Machiko Kyo) and the murder of a man (Masayuki Mori), possibly by a bandit (Toshiro Mifune), is presented entirely in flashbacks from the perspective of four narrators. In each of the four versions of the story, the characters are the same, as are many of the details. But much is different as well.

Kurosawa created a new cinematic language where though the same incident is narrated again and again and again, yet every version maintains the taut tension throughout, keeping a tight grip on the viewer’s attention. The radical nature of the storytelling was unfathomable by many at that time, as a result of which even the producers weren’t happy with the yet-to-win-international-acclaim Kurosawa.

It was only after Rashomon proved to be a breakthrough film at the biggest International festivals that peace was restored on the home front and the Japanese film goers began to take both the film and the maker seriously.

3. Breathless

Post WW II, there was an onslaught of classic Hollywood films in France with their archetype heroes and stereotyped narration. Hence Breathless became a beautiful statement on celluloid from Godard that showcased how filmmaking was not about rules, conventions, big budgets and the studio system. Post this, other iconic films that came out of the Nouvelle Vague too followed suit asking and answering pertinent questions about the French identity.

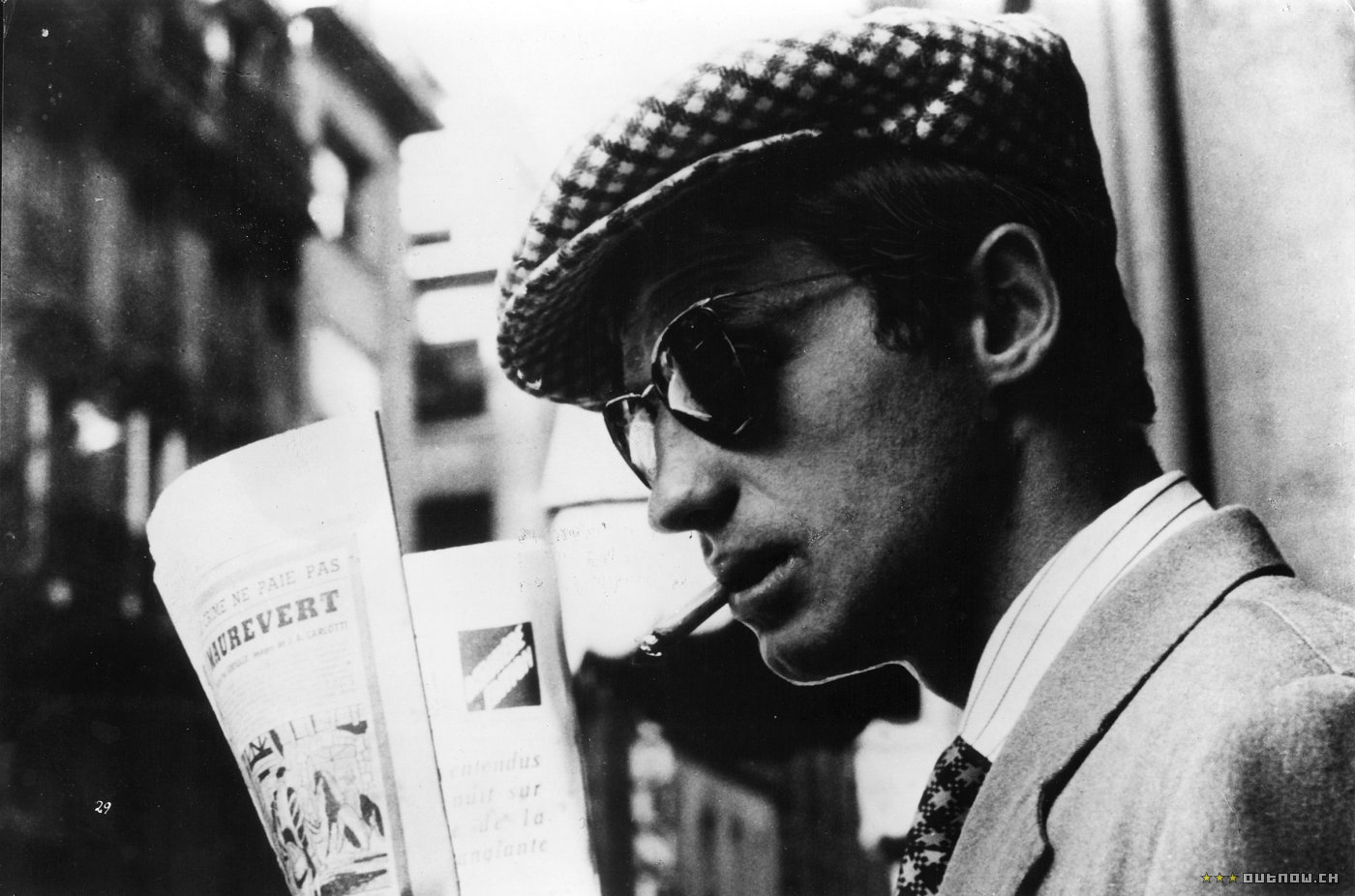

Breathless or A Bout De Souffle opens with Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo) a young hoodlum, who after stealing a car in Marseille, heads for Paris, gunning down a cop on the way. Once in the capital, he meets American student Patricia (Jean Seberg), an aspiring journalist who sells copies of the New York Herald Tribune on the Champs-Elysee.

Patricia agrees to hide him while he tries to trace a former associate who owes him money so that he can evade the police dragnet and make a break for Italy. But as the authorities close in, she betrays him, leading to a final shoot out in the street.

Godard decided to give the film a documentary-like look, shooting with a handheld camera and natural light. He innovated with a wheelchair for tracking shots and used specialist lowlight film stock for night shots. Godard’s method of directing and editing was equally unorthodox.

Instead of cutting out whole scenes, he decided to cut within scenes. Hence jump cuts were born. By deliberately appearing amateurish, Godard proved that conventions of classic cinema were what they were, merely conventions.

2. Mirror

The poet of celluloid, Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky’s autobiographical film Mirror was released in 1975. Mirror is a cinematic treatment of memory recollection through dream sequences and archive footage that traces the past of a dying man.

Due to its non-linear structure, Mirror opposes the classic narrative cinema. Unlike his other films which had a beginning, middle and end, Tarkovsky decided to abort a normal structure for Mirror, the logic being that we humans don’t dream and recall events in any chronological order.

So Mirror doesn’t have any storyline and is structured in fragments like the act of remembering, with no temporal order or with an apparent causality. This is why Mirror stands in stark contrast to a narrative.

The film is about the memories and reflections of a forty year old dying man, Alexei. It is told with various vignettes from his childhood intermingled with scenes from his present condition. It is confusing for the first time viewer as the sequences break the narrative style, jumping back and forth in various time frames without any explanation. Though it is his personal memoir, Tarkovsky was unsure of how to put the story in a chronological order.

As it turned out, along with screenwriter Aleksandr Misharin, both started filming with many unresolved structural issues. This is what he said about the structure,” the scripts of my earlier films were clearly structured. For Mirror, we made it a deliberate point of principle not to have the picture worked out and arranged in advance, before the material had been filmed.” Truly a work of art from a master that is absolutely radical.

1. Citizen Kane

Structured largely through the recollections of supporting characters, including Kane’s best friend (the great Joseph Cotton) and the showgirl who inadvertently bungled his political aspirations (Dorothy Comingore), the story of Citizen Kane is as much about the psychological bruises and the impenetrability of public figures as it is about their quirks and enigmas.

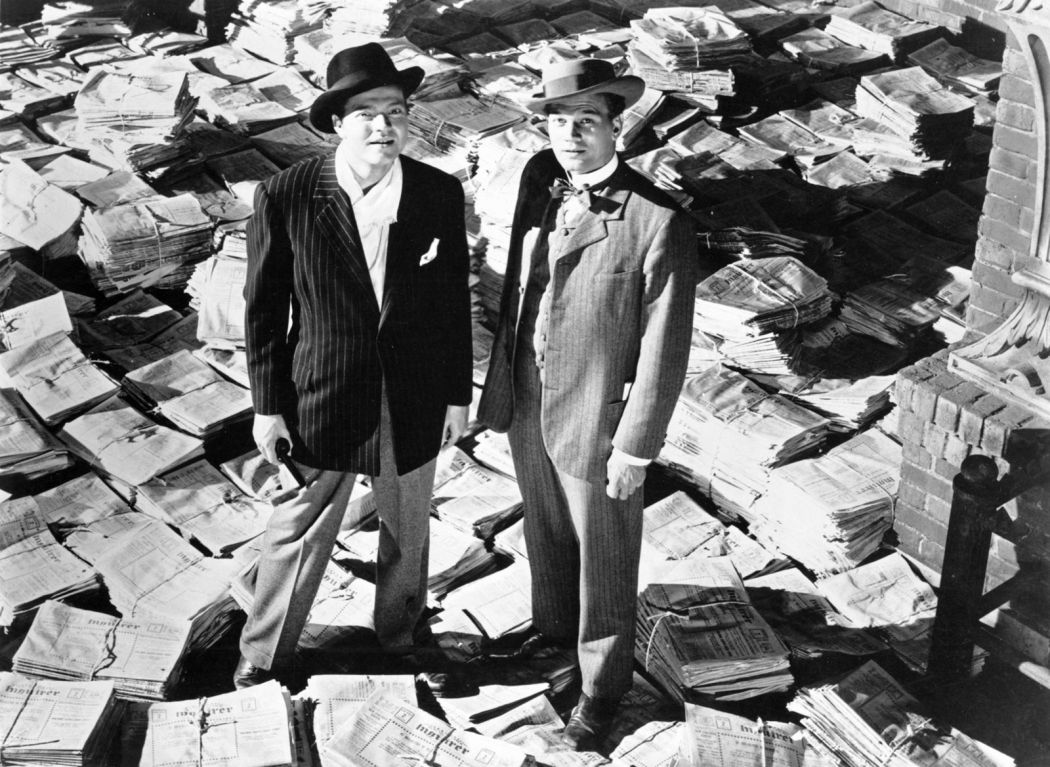

The film begins with a mythical short on the life of the great publisher, Charles Foster Kane, who has just died. As Kane breathes his last, one word is heard to escape his lips, “Rosebud,”. A reporter from “News on the March” then begins the monumental task of checking Kane’s life to find out what he meant when he uttered his last word on earth.

Each person’s recollection describes a specific phase of his life beginning with his infancy in the West when he inherits a fortune. The drama critic, the lawyer, the butler and his publishing aide all contribute to the Kane saga, but the dramatic highs come mostly from the memory of his second wife, who is by now wallowing in her alcoholism.

The support he gets from his cast of new faces is downright amazing. The person behind the camera – Gregg Toland captured the actors from daringly unusual angles to compliment the narrative. Though the main credit must without doubt go to Orson Welles for his fine attention to detail, meticulous storytelling, and the utmost care he took to craft his art that makes Citizen Kane so special.