6. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Though on the surface they were quite different, Robert Bresson and Stanley Kubrick might well have had a lot in common for discussion. Both called the shots (and complained long and loud about the few times that they didn’t). Both carried themes and ideas from film to film and used the same stylistic devices, though the films were always unique on the surface. Both aimed for a unified whole with which to express their ideas. Both had great champions among critics (and great detractors as well). However, one was forever destined to be a critical/cult denizen and the other a box office champion (at times, anyway).

“2001: A Space Odyssey” was, all things adjusted, Kubrick’s biggest hit and a film that captured the adoration of the critics, if one also makes adjustments for the lapse in time it took for that to happen. It is also the biggest and most successful art house film ever, though it’s seldom perceived that way.

Many in the huge crowds that swarmed to the film in initial showings and early re-releases claimed they enjoyed it as a sensory experience (especially the sequence where the spaceship enters the atmosphere of Jupiter) but couldn’t begin to explain what they saw.

The film is really about the way mankind meets and adapts to seismic evolutionary changes. That sounds weighty, doesn’t it? The miracle is that Kubrick managed to make a film that states this without any compromise or artistic missteps and still have people come.

Many have commented that the film’s only major acting players, Keir Dullea and Gary Lockwood, both seem wan and uninteresting and pale next to the highly animated computer H.A.L. (and Dullea, at least, was far from wan or uninteresting as an actor normally).

This is purely by Kubrick’s design in developing an ongoing theme about how “civilization” and all it embraces has taken the humanity out of humankind, and how various human accomplishments have become more interesting than people (and his choice of distinguished Canadian stage actor Douglas Rain to provide the unforgettable voice of H.A.L. was far from coincidental).

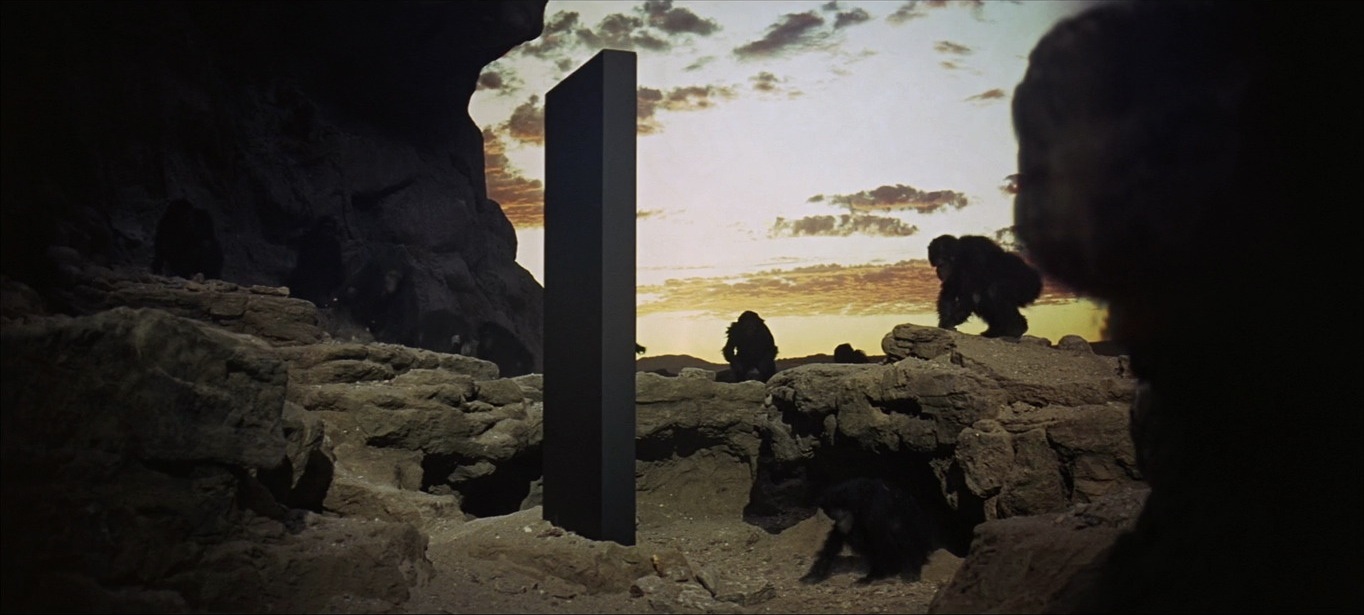

Also not left to chance was the carefully choreographed dawn of man sequence (so convincing that very few realized that actor/dancers were playing the ape-people in this section and weren’t really animals!), nor the lengthy outer space sequences (and Kubrick didn’t hire FX men, he became one and did this work himself!).

One supreme example of his perfectionism is the fact that Kubrick cut nearly 20 minutes of footage from the film after the premiere and made quite certain that it would never be reinstated. He had thought better of it and decided that the footage’s removal would indeed make his masterpiece perfect.

7. Fanny and Alexander (1982)

Ingmar Bergman spent his adult life in the theater and in films. It’s not strange that he put so much of that life into his works. Quite often, the intense psychological struggles his characters have with one another, and the concept of God and meaning came from this thoughtful and conflicted man’s inner being and the stories of his own life (and it’s no coincidence that he was personally involved for long periods with several of his lead actresses).

When he announced that he was retiring from film in the early 1980s (which he only semi-succeeded in doing), many were waiting for a project that would sum up one of the great careers in cinema history (and what a shame that he ended up dying the year before a Nobel Prize for film was created!). Well, he delivered not only a perfect capstone, but perfect entertainment as well.

“Fanny and Alexander” is a family story, as were many Bergman films. It is set in a milieu of those who spend their lives in the theater, also familiar Bergman territory. It is a period film, set early in the 20th century, famously the time in which Bergman grew up himself.

Bergman is surely represented by Alexander, the beloved son/grandson of the wealthy theatrical family (Fanny is his little sister). The children become involved in a rich Dickensian plot that sees their father succumb to an early death and their confused (though loving) mother being lured into an ill-advised (and hasty) marriage to a cold and ultra-stern bishop (and anyone acquainted with Bergman’s work knows that clergyman are always bad news in his films, a fact that goes back to Bergman’s own minister father). The children’s salvation by their clever grandmother and her longtime Jewish companion brings the film to a satisfying conclusion.

This story was shot to be seen as a long-form miniseries in some places and a (lengthy) feature film in others. The miracle of it all is that, though the thrust of work is different with each format, the piece works beautifully both ways.

Though it was regrettable that Bergman couldn’t get some of his famed players such as Max von Sydow or Liv Ullmann (who was offered but said no for personal reasons) into the film, the cast, largely from the stage, is perfectly chosen.

Also perfect are the Oscar winning sets, costumes and cinematography (by Bergman regulars such as cinematographer Sven Nikvist), all of which helps this film add up to the most perfect entertainment in Bergman’s canon.

8. Wings of Desire (1987)

One might well think that the artificial but seemingly realistic nature of film would make it a perfect medium to convey a weighty, spiritual concept. Many a pretentious and/or silly film trying to do just that would seem to prove this idea wrong. But then, a film that really gets it right, such as “Wings of Desire” comes along shows that it is possible. “Wings” is one of the most ethereal films ever created and never seems to misstep or fall into foolishness.

Wim Wenders was one of the strongest directors to emerge from the era of the New German Cinema. As with so many on this list, he knew what he wanted and was determined to have his films state what he wanted and how he wanted it stated. As with many in those pre-unification times in Germany, he pondered, through his films in his case, where the country was and where it might be going.

To this end, he created a story of Germany largely seen through the dispassionate/compassionate gaze of two angels who hover above the then-divided city of Berlin, simply observing, until a lovely circus aerial artist (who, of course, works close to Heaven) unwittingly captures the attention of one of the angels, who decides to descend to earth. Preposterous? Maybe in theory it is, but in fact, it isn’t.

Much of the fact that this film pulls it all off must go to some perfect creative decisions. The cast includes such excellent players as Curt Bois, Otto Sander and Solveig Dommartin, but the crucial casting is the superb German actor Bruno Ganz as the angel come to earth. With his strong features, limitlessly kind eyes, and perpetually gentle, yet firm demeanor, who could have played this role any more perfectly (certainly not Nicolas Cage, who took the role in the film’s far from perfect US remake)?

Also perfect is the casting of veteran Hollywood star Peter Falk as, ostensibly, himself, but turning out to have more… well, cosmic resonances than might be expected at first glance. Also perfect is a script which skillfully switches from a Heavenly perspective to a human one (the angels can hear all human thoughts and read hearts but actual interaction becomes a different animal altogether).

The key to actualizing this is in the films most perfect choice: the cinematography shot in both color (earth) and black and white (Heaven). Using the great classic era cinematographer Henri Alekan (forever known for his unforgettable work in Jean Cocteau’s 1946 “Beauty and the Beast”), the lovely colors pale beside the lush and atmospheric monochrome, which creates a cinematic Heavenly realm which is unparalleled in the film world.

Much like the aerialist heroine, this film is a real high-wire act without a net but, like a good aerialist, it makes all the right choices and stays aloft. (The film’s sequel, “Faraway, So Close” shows just what could have gone wrong here.)

9. Pulp Fiction (1994)

This list has focused on filmmakers who are strong and bold enough to make sure their films are made their way, and who achieve perfection within the scope of what they wish to accomplish when things all go the right way. The majority of these film artists aim for the highest and best. This is where the artist at the heart of “Pulp Fiction” somewhat parts ways with the others.

Quentin Tarantino, a writer/director who famously learned much of his trade working in that now extinct location called a video store (sez he), broke into films via his writing skills. The thing that distinguished him was that he didn’t at all want to make the next “Lawrence of Arabia” or “Gone with the Wind” as much as he wanted to revive the glory of kung fu or blaxploitation cinema.

In other words, he loved good trash and really sought to turn the elements of good trash into non-highbrow cinematic art. He was also working in the realm of “found art” in cinematic terms.

Though he has now made nearly a score of films, for many the apotheosis of what he seeks to do is what was, surprisingly, only his second film, “Pulp Fiction.” After causing waves in the film cult community with the darkly witty violent caper film “Reservoir Dogs” (1992), he was set to make the film he always dreamed of making, an action packed comedy/drama with a crime background and a surprising amount of deep thoughts disguised in the margins.

Though the cost wouldn’t be exorbitant, the finished film would be long (some two and half hours, as it turned out) and would tell three interrelated stories, told somewhat out of chronological order, though in a manner that would make the stories more meaningful for it all.

For his cast, he wanted interesting little-known actors, some familiar faces who had yet to break through, and some who were, to be blunt, considered has-beens. He would also fill the picture with loads of references to pop culture and (of course) cinema and overlay it all with a rich soundtrack of classic pop tunes (and classic surf tunes got a big boost from this film).

The jaw-dropping thing is that it all worked! Debuting at Cannes, the buzz around the film quickly grew around and it became the talk of the cinematic world for a couple of years. Why? Well, it is/was audacious and striking, but it’s also perfect in its “rightness.” The stories and the way the script (by Tarantino and Roger Avery) rejiggers the time line play out wonderfully well, especially since the perfect cast for the roles makes them come to life.

Now they all seem like logical choices, but the superb Samuel L. Jackson was a stage actor unknown to film audiences; the luminous Uma Thurman known only for her supporting debut in the critical but not box office favorite “Dangerous Liaisons” (1988); Bruce Willis was the critically drubbed “Die Hard” guy from TV; and John Travolta was an actor two decades past his sell-by date (trapped in the disco era by 1978’s dynamic “Saturday Night Fever”).

Added to this were then unique choices such as Ving Rhames, Christopher Walken, Eric Stoltz, Rosanna Arquette, Harvey Keitel and several others, perfectly bringing highly interesting and original characters to life in order to supply a great richness to the film.

All of this and many other elements (such as the fabulous Jack Rabbit Slim’s set) were all juggled which what looked like the greatest of virtuoso ease by Tarantino. Thanks to the perfection of its choices, the film made sure that neither Tarantino’s career, Miramax, nor the course of US independent film making would ever quite be the same again.

10. No Country for Old Men (2007)

The final selection on this list will be one which could engender much critical thinking. Few would argue that the Coen brothers possess the strength of character and talent that mark the other filmmakers on this list, or that, like the others, they have created a cinematic universe with their films, which could only have been made by themselves.

Few could also argue that the technical end of things (cinematography, sets, often in period, and costumes) are always impeccable. However, for many, their films often (if not always) take what is termed a “left turn” into unexpected territory. For many of those who think along those lines, the ending of “No Country for Old Men” is the most left turn of them all.

First of all, it should be noted that this film is a rare adaptation for brothers Joel and Ethan Coen (most of their best known works have been originals). Not only is it an adaptation but it is one that was taken from the most distinguished source of any Coen adaptation, namely the eponymous novel by the much acclaimed modern American writer Cormac McCarthy.

Perhaps it’s a pretty good indication of the ratio of readers to film goers that so many were taken aback by the last act of the film since it is quite faithful to the novel and its themes (like the Coens, McCarthy is a true and subtle artist and doesn’t go for the obvious).

However, even if the viewer knew nothing of the novel, the skillful way the film was developed should have let any discerning viewer know that this piece wasn’t going anywhere expected, but often viewers look without seeing, hear without listening, and take in without analyzing what they have ingested.

On the surface, “No Country” is a crime/caper film set in the rural US southwest in 1980. While out hunting, a rather feckless youngish man (Josh Brolin) finds the scene of a drug deal gone very bad indeed.

All of the parties directly involved have killed one another and left behind some $2 million. Not being really bright enough to realize that the money has an owner somewhere who will want it back (or being too financially desperate to care, given his lower middle class status), thinking that no one will ever know, he takes the money.

Sure enough, soon thereafter two hired killers (Woody Harrelson and an Oscar-winning Javier Bardem), one of them especially strange and lethal, are on the trail of the money and will kill absolutely anyone who gets in their way. The only hope of setting things right is the area’s weathered and weary, but morally strong sheriff (Tommy Lee Jones), who is tracking all parties involved in hopes of preventing further violence.

This sounds like another tough crime and punishment film with local color. Actually, it could, if one wishes, be considered the hot desert cousin of the Coen’s famous “Fargo,” right down to its theme being encapsulated in the last big speech given by Frances McDormand’s sheriff in that film. Both films speak to how larger forces might well control people’s lives (quite pointedly made here by the lethal coin tosses of Bardem’s character).

They also both examine how greed and cruelty can wreak havoc on somewhat innocent lives. One big difference is that “Fargo,” being a comedy, albeit a black one, can find a tidy-ish ending for its deserving heroine, while this film realistically finds a continued struggle for its sheriff. The forces of bad will continue and will affect many lives, but good must continue to fight back for there to be any hope. Conventionally satisfying? No, maybe not, but honest and illuminating.

All of that being said, the look and feel of the film is perfect for its time and place. The cast is perfectly chosen with no weak links. Even Bardem’s intentionally awful hairstyle is perfect (it speaks to the character perfectly and is unforgettable). For those who aren’t in tune with the Coens’ work, this film may not be perfect at all. For those who are, it’s one perfect representation of their work.

Author Bio: Woodson Hughes is a long-time librarian and an even longer time student/fan of film, cinema and movies. He has supervised and been publicist for three different film socieities over the years. He is married to the lovely Natalie Holden-Hughes, his eternal inspiration and wife of nearly four years.