Surrealism as a genre, not only solely in the realm of cinema, but in art as a whole, has always sparked some intriguing discourse among intellectuals and general audiences alike. A piece of surrealist cinema differs greatly from that of conventional films in the sense that ostentatious elements such as symbolism, theme and style take precedence over the standardized rules that bind cinema.

The films on this list are pieces of absolute genius that may not make complete sense to general audiences and may not even be good pieces of filmmaking to begin with, but are still undeniably works of art, no matter how bizarre they might outwardly seem, that should be dissected for what they’re worth. Without further ado, these are the 10 strangest surrealist films.

10. House

Japanese cinema, and more specifically, J-Horror, has always shocked the world in terms of how utterly mad the content and craft can be. Nobuhiko Obayashi’s 1977 cult-classic, House, has a simple enough premise that may very well be a carbon copy for a myriad of other forgettable horror films.

It tells of a simple tale of a group of teenage girls that find themselves in a haunted house where they slowly get picked off one by one. This logline seems normal enough for conventional horror standards, but Hausu is anything but.

Though it does adopt a conventional structure constricted by this simple premise, the way the sequence of events plays out and the general look of the film is very much akin to a bad trip on LSD.

There’s frankly not much to take away from the film beyond a superficial level but the imagery is so incredibly vivid, so utterly insane, so bold and innovative considering the fact that this is a film released in the 70s. Obayashi uses such filmmaking techniques that may come across as outdated to today’s audiences, but the way he utilises them still holds up today 40 years later and manages to bewilder with his singular style.

If you haven’t seen or heard of the film, consider one of the most infamous scenes of the film involving a piano literally consuming a girl. That alone sounds crazy enough, but you don’t know crazy until you’ve actually seen how Obayashi shot that scene, along with countless others in the film.

9. The Blood of a Poet

Who would have ever thought that a film just a mere 50-minute runtime would be so incredibly overwhelming. True surrealist cinema, free from any glamour or regard for film grammar, is understandably inaccessible. However, Jean Cocteau’s abstract portrait of art may very well stand out as the most grandiloquent of the lot.

The Blood of a Poet tells its story in 4 acts. 4 outwardly simple tales surrounding a single artist and the strange events he experiences. Cocteau presents his concepts through a series of bizarre imagery, ones that manage to somehow or rather, maintain a slight foothold within both the realms of reality and fantasy.

Though the film’s message seemed a tad too over-arching in scope, the overall intended effect of the film still works. The self-reflexive, poetic and abstract nature of a creative mind, properly represented in all its ostentatious, unabridged cacophony.

The Blood of a Poet may be short and nicely split into 4 distinct episodes that stay structurally coherent unlike other surrealist films of the era like Bunuel’s Un Chien Andalou, but it still has enough heavy-handed symbolism to perplex and challenge our own understanding of the avant-garde.

8. Wrong

Quentin Dupieux’s Wrong is nowhere near a decent film. Regardless of how much we as an audience choose to ignore it, there is an undeniable line between absurdist cinema and terrible cinema and though it strives for the former, Wrong is, for the most part, a terrible piece of film.

Nevertheless, if we choose to abandon the conventional rules of right and wrong when it comes to criticising film, and we accept Wrong for what it is, which is an ugly manifestation of a filmmaker’s creativity, it stands tall.

Beneath the farcical plot of a man losing his dog, Dupieux explores the theme of empathy through its quirky cast of characters, portraying it through an uncanny yet grounded reality filled with deadpan absurdism with an unusual interpretation of the “Only Sane Man” trope.

It’s truly nothing short of an amazing feat to make a film so fundamentally flawed, with a visual style not too different from your typical YouTube skit, complete with terribly acted performances that may or may not be intentional, and in spite of it all, still manage to have its heartfelt moments. Moments where we connect to the characters and their plights in the same vein as how we accepted the world Lars von Trier built, or didn’t built with Dogville.

Wrong is a film that, as the title suggests, is wrong. It fails on almost every aspect of technical filmmaking, focusing solely on theme and for some bizarre reason, it managed to make us as an audience, overlook the flaws of its craft and that, in and of itself, is an achievement.

7. Pink Floyd – The Wall

What an incredibly spellbinding experience to say the least. Forget The Rocky Horror Picture Show, when it comes to cult musicals, Pink Floyd: The Wall is on a league of its own. A true unparalleled masterpiece in storytelling, serving as perhaps the most unique and poetic companion piece to a work already poetic and unique.

This is a film so much more than just a mere reimagining of an album. The subjective yet universal perspective built by the film is one that transcends its capacity as a fictional character study. Nothing that happens in the film is strictly speaking, coherent, and it certainly doesn’t follow any austere sense of structure beyond that of the album track listing. Nevertheless, the pure boldness, innovation and sheer emotion that exudes from this film is insurmountable.

The way Pink Floyd: The Wall is able to juxtapose such contrasting imagery, between what’s objective and subjective, what’s real and surreal is so incredibly seamless to the point where the cacophonous buffet of extravagant symbolism is made lucid and comprehensible. This is an experience unlike any other and if anything, provides a fresh outlook on how to deliver an engaging character piece as well as pay homage to an already existing great.

It’s a masterclass and an absolute tour-de-force in surrealist cinema in all its bizarre facets, from the music to the editing, the set design to the performance, to the brilliant style of animation that just gives such palpable weight to this otherworldly cinematic achievement.

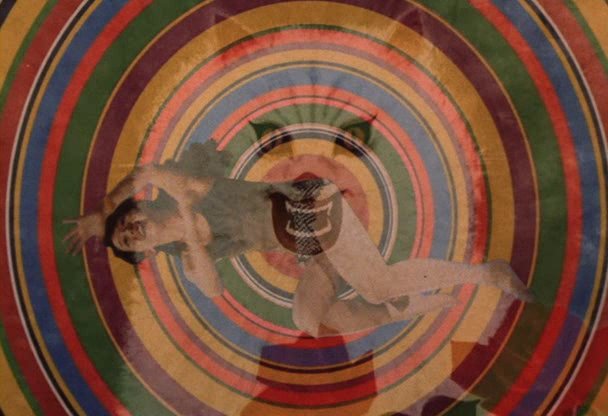

6. Paprika

Comparing Paprika to its spiritual successor, Inception from an objective standpoint would be entirely unjust. While Nolan’s film placed its focus on crafting a coherent, complex neo-noir set in a well-established world of dreams, Satoshi Kon’s Paprika focused on theme and the raw exuberant cacophonous flow of emotion that comes with such a hedonistic world.

The images put to screen in this abstract masterpiece are just so insanely surreal and seamless. The world built may not be quite as comprehensible as that of Inception’s, but is Satoshi Kon’s interpretation of the state of dreaming really to be considered a flaw? Kon brings to life the insanity, the freedom, the vibrancy of dreaming in a jaw-dropping amalgamation of cinematography and editing pushed to the sheer limit in the world of animation.

Paprika examines dream in all its facets. The themes and concepts that exude from this state of limbo. The conflicts and ideologies that stem from it. Everything is stitched together in a narrative that doesn’t quite make complete sense, but is undoubtedly realised to its absolute completion.

The lines between fantasy and reality are broken and bent out of proportion when it comes to the state of dreams. Filmmakers like Kaufman and Nolan have told incredible stories perpetuated against this hypnagogic domain. But not they, or anyone else for that matter, have quite explored it like how Satoshi Kon did with Paprika.

Dreams have never felt this real.