10. Spellbound

What happens when you mix Alfred Hitchcock with Salvador Dali? One hell of a trippy dream recollection, in the underappreciated film Spellbound. The man named “John Brown” (who is actually an imposter that already went under the guise Anthony Edwardes earlier) recounts a subconscious scene which starts off with a series of drapes cloaked in eyes being cut by scissors. A faceless proprietor yells at a gambler during a card game; this same proprietor hides on top of a roof after a bearded man commits suicide. Finally, “Brown” remembers being chased down an obscure landscape by imaginary wings.

Visually, this whole scene is exquisite, with enough of a Dali touch to feel like we are in one of the surreal mastermind’s paintings. Conceptually, the weird physics and images we are used to in our dreams is almost pinpoint accurate.

9. 3 Women

Like other entries here, you can argue that the entire film might make sense here, because we are never really sure what is even real to begin with here (or if any of it even is real). For obvious reasons, it’s best to go with one of the parts that’s actually acknowledged as a dream, and that’s Pinky’s nightmare at the start of the final (and quite bizarre) act. Fish swim over Pinky’s body, and the pool artwork by Willie start to get embedded on top.

Damning music is mixed together with frantic whispers and sobs. Scenes from earlier get played in a new demonic way. If audiences didn’t think they stumbled into the wrong movie in earlier scenes, this moment surely sealed the deal, as it’s the exact moment that a Robert Altman film went from mainstream right into avant garde.

8. Brazil

Sam Lowry fights the disappointing American Dream by concocting his own through daydreams on a reoccurring basis. These dreams form one long surreal story, involving Lowry as a mighty hero that saves the love of his life (who begins to appear in his real life).

As Lowry’s life in bureaucracy (and the 1984 influenced political climate, no less) gets more troublesome, his dreams start to get more frightening. Lowry appears as the villainous samurai he fought to stop (or is it a Sam-or-I), familiar faces begin to seep into the environments, and more tribulations are thrown his way. Things get freakier when visions from his dreams haunt him in real life, and by the end of the film, you won’t be sure what was real at all this entire film.

7. Rosemary’s Baby

The titular Rosemary had been through a lot by the time this scene rolls up. Her and her husband Guy have recently moved in to an apartment flat. They get constantly noticed by the Castevets, and they had just witnessed a brutal suicide. Nonetheless, Rosemary and Guy want to have a baby.

However, she passes out, and has a disturbing nightmare instead. She’s on a boat with familiar faces one minute, and soon after finds herself in what looks like the fiery pits of hell surrounded by these same people (now naked). Blood is painted on her, and she opens her eyes to find herself being raped by a demon of sorts. She wakes up to Guy saying they conceived while she was sleeping, but we are never sure about anything from that point on (rightfully so).

6. Wild Strawberries

In Ingmar Bergman’s existential drama, Professor Isak is on his way to receive a prestigious academic degree. His internal anguishes plague him, because he feels he has not fulfilled his life and is close to death. One of the ways these fears haunt him is through vicious dreams. He narrates one such dream, where he walks a street alone. He fixates on a clock that is missing its hands (time is irrelevant here). He approaches a man with an abnormal face, who collapses and gushes blood from his head.

A horse drawn carriage bashes into a lamp post repetitively, and a coffin slides out of it. Isak pulls the hand of the corpse inside, only to find that he is pulling his own hand; the dead Isak pulls the living Isak in and prepares him for death. The scene is washed out like a Fritz Lang silent flick, but all of the eerie sounds are still present to spook us.

5. The Discrete Charm of the Bourgeoisie

Again, we have an example where any part of the film could really be featured here, because, well, none of The Discrete Charm of the Bourgeoisie is explicitely real. This film is one of Luis Buñuel’s finest achievements, because it’s nearly impossible to really classify this film as anything outside of a surreal satire. Do we pick the shocking part where all of the dinner guests are shot on sight? What about the curtains opening, with the dinner party being in front of a live crowd? The part where everyone gets arrested is hysterical.

No, I’m going to pick the French colonel’s nightmare moments. There are many jaw dropping parts, including the piano being used as a torture device (with cockroaches falling on the keys), and the bloodied ghost. It’s as if Buñuel revisited Un Chien Andalou decades later, but with a higher framerate and with blistering colour. It’s the most unsettling part in an already jarring film.

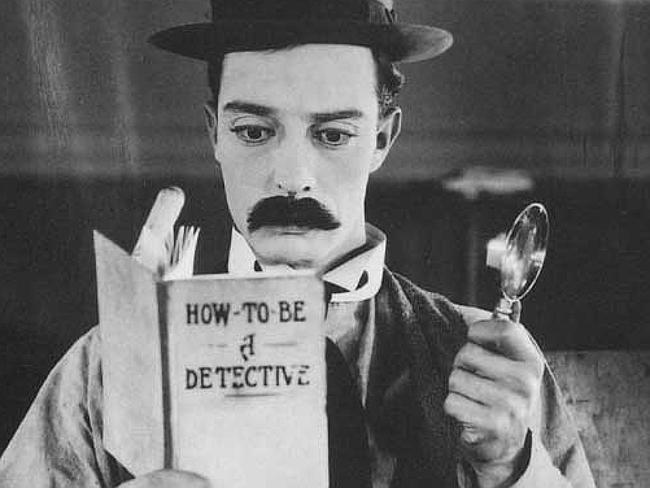

4. Sherlock Jr.

There’s nothing a cinephile would like more than to dream that they were in movies (well, that’s my guess anyways). That dream comes to life in Buster Keaton’s exemplary silent film Sherlock Jr., where a projectionist finds himself welcomed into a film by the characters being cast onto the screen. We witness the projectionist’s adventures from the crowd, as all of this takes place on the screen.

If that wasn’t intriguing enough, he finds himself caught between one of cinema’s greatest achievements: the dreaded jump cut. Keaton brilliantly places his own character in situations that serve for inventive slapstick comedy, including the projectionist readying to sit on a bench, only for the scene to change and the bench disappear entirely (of course, he lands on the ground). Throw in other hilarious examples, and you have a classic silent film moment.

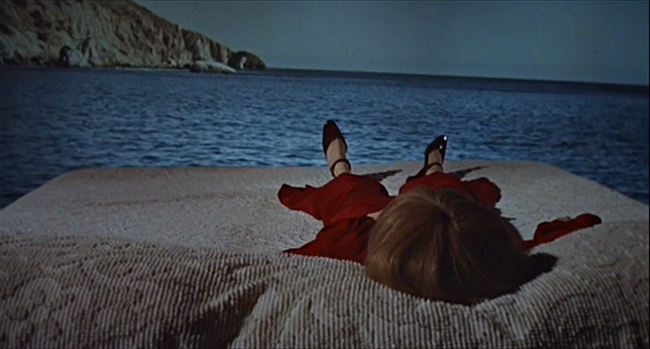

3. Vertigo

I tried to stick with one film per filmmaker for this list, but Alfred Hitchcock is an exception, because the two works featured are combined efforts with the artists that took part in the respective entries. Salvador Dali was first, and now we have John Ferren (who actually painted the Portrait of Carlotta which serves as a major symbol in the film).

Scottie lays restless in his bed, only to be flooded by bright colours. He suddenly opens his eyes and sees an animated bouquet disassembling (one that looks like it came out of Disney’s Fantasia). He revisits earlier scenes, with the bright colours still flashing. Suddenly, his detached head is in a vortex, and his lifeless body is falling into oblivion. Even though the effects have aged quite a bit, the creativity renders this moment iconic to this day.

2. 8 ½

There are a number of excellent dream moments in 8 ½, but we might as well pick the opening three minutes that set the tone of the film. Guido Anselmi is a struggling film director; he battles his adulterous ways, and his writers block, both of which are preventing him from fulfilling his latest movie vision. Before we even know any of that, we start off with a gorgeous dream.

Guido is stuck in traffic, but the traffic is so bad that it looks far more like a collection of toy cars placed together (and not even a parking lot). Either faces stare out of car windows, or limbs hang out of them. We can’t hear much aside from Guido’s anxious breathing and a cool wind. Guido breaks out of his car (he can’t open it normally for some reason), and is suddenly free enough to fly in the sky. He finds himself tethered, like he is a kite soaring, and his limp body comes crashing down into the sea below. We know nothing but are prepared for anything, now.

1. Mulholland Drive

Well, we made it to number one. David Lynch had to appear on a list like this, and his surreal neo noir masterpiece Mulholland Drive takes the cake. Really, you can consider most of the film an entry for this spot, because the majority of it is a subconscious Neverland. If we have to pick one scene alone, which do we go with? The scary Winkie’s encounter? The stumbling on the dead corpse? Camila Rhodes’ blissful audition?

We’re going to go with Club Silencio here for a number of reasons. First off, it is the first key reminder to Betty that she is actually Diane in a dream world. She shakes once she realizes that everything is an illusion, thanks to the cues from the persistent emcee. Her fears are subdued by a Spanish rendition of Crying by Roy Orbison (sung by Rebekah Del Rio); Del Rio faints mid-song and the singing continues, just reiterating that we are witnessing a lie.

This isn’t the first wake up call for Betty, but the first major one for the audience, too. Sure, we knew we were watching something surreal, but this was the first actual clue that it may not even be real. To top things off, we get the blue haired patron from that same club cueing the end of the film; she softly says “Silencio”, and ushers us out of the cinematic experience and into the real world. Club Silencio is beautiful, devastating, serene, and frightening. It may very well be the best dream sequence in cinema history.