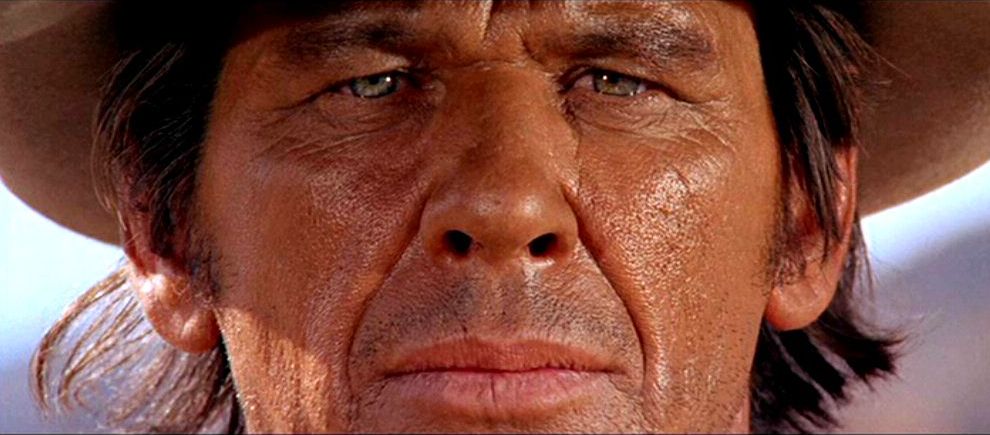

10. Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

Spaghetti Westerns feel more spectacular and polished than traditional westerns. In this sense, Sergio Leone stands out as the key figure of this unofficial film movement, and “Once Upon a Time in the West” is perhaps his most accomplished film.

In the final duel between Frank (Henry Fonda) and “Harmonica” (Charles Bronson), the reason behind the mysterious gunslinger revenge is revealed. In the past, Frank forced a kid to support his older brother on his shoulders. The neck of his brother is tied to a string. Frank puts a Harmonica in the mouth of the little kid and asks him to play. The older brother kicks the kid away and dies, while his younger brother falls into the desert dust dramatically.

Throughout the entire film, Harmonica’s motivation for hunting Frank is undisclosed. When the climax arrives, Leone masterfully delivers the cause of the vengeance with this stylish scene. In addition, Ennio Morricone’s score also reaches an emotive yet aggressive tone that makes Harmonica’s fall into the dust maybe the most sublime moment of the film.

9. Carrie (1976)

The slow motion scene in “Carrie” is executed in a very powerful manner. It depicts the ignominy of bullying and the cruelty of vengeance in a exquisite display of blood and violence. The prom scene of “Carrie” will always be iconic because the brutality of its themes have never been shown with such grotesque filmic elegance.

After Chris Hargensen (Nancy Allen) is banned from the prom, she makes a plan to give Carrie White (Sissy Spacek) the ultimate humiliation. With her boyfriend they install a bucket of pig’s blood over the school’s gymnasium stage. When Carrie is crowned as prom queen, the pig’s blood is spilled on her. Carrie believes that everyone in the room is mocking at her, so she kills them in a bloody sequence of telekinetic slaughter.

When Carrie is bathed with the pig’s blood, it seems that the beginning of madness and chaos is imminent. Brian De Palma had the delicacy to not unleash the pandemonium right away, and allowed Carrie to slowly enter into morbid hallucinations through the aforementioned slow motion scene.

8. In the Mood for Love (2000)

Wong Kar-wai’s “In the Mood for Love” is a film that develops its most rich values in the finesse of its daily habits. Its intoxicating pace reveals the hidden emotions that overwhelmed Su Li-zhen (Maggie Cheung) and Chow Mo-wan (Tony Leung) through, perhaps, one of the most sophisticated filmic tones ever delivered onto the silver screen.

In this regard, the corridor glance scene speaks volumes of the secret romance that both Su Li-zhen and Chow Mo-wan live. The sensuous walk of the lovers, the standby moments, and the role of the food express the intense emotional strain that affects them using image and sound in the finest way possible.

Nostalgic and romantic, “In the Mood for Love” is a tribute to the fragility and ephemeral nature of passion. As Wong claims at the end of the film, “He remembers those vanished years. As though looking through a dusty window pane, the past is something he could see, but not touch. And everything he sees is blurred and indistinct.”

7. Don’t Look Now (1973)

The opening sequence of “Don’t Look Now” is a lesson of how a film should present itself. While John Baxter (Donald Sutherland) is reviewing slides of a church’s stained glasses and Laura (Julie Christie) is reading near the chimney, their kids are running in the open field.

Christine (Sharon Williams) and Johnny’s (Nicholas Salter) movement in the forest, somehow, is echoed in the activities that John Baxter carries out. Christine falls into a little lake and a red stain s over John’s diapositive. A synchronicity moment happens.

John feels that something is wrong. He goes outside and notices that his son is also calling for him. He runs into the little lake and encounters his daughter drowned in the water. The slow motion, in this case, depicts the useless and desperate attempt to save her in a very moving scene.

6. Full Metal Jacket (1987)

Stanley Kubrick’s last war film “Full Metal Jacket” perhaps doesn’t possess the ferocity and madness that some Vietnam War pictures like “The Deer Hunter” or “Apocalypse Now” present. Its richness relies, perhaps, in a comedic and at times moral vision of the experience that soldiers had both before the war and in the war itself.

By the end of the movie, the squad is losing its members one by one. At the same time, the battlefield feels more and more like a labyrinth. Cowboy (Arliss Howard) instructs Eightball (Dorian Harewood) to investigate where they are, because he feels the crew is probably lost. At that moment, a sniper begins to shoot.

While trying to cope with the situation, Doc Jay, Eightball and Cowboy are killed. The impact of the bullets penetrate their bodies, and the slow motion stylized the collision in a sequence that immortalized the figures of the soldiers as victims of the brutalities of war.

5. Reservoir Dogs (1992)

The title sequence of “Reservoir Dogs” still feels as fresh as when it was first released. The scene introduces Quentin Tarantino’s particular directing approach on his own terms; that is to say, by presenting a stylish walk filled with coolness and vitality that, at the same time, impregnates the rest of the movie with a particular filmic tone.

While Mr. Blonde (Michael Madsen), Mr. Blue (Edward Bunker), Mr. Brown (Quentin Tarantino), Mr. Orange (Tim Roth), Mr. Pink (Steve Buscemi), Mr. White (Harvey Keitel), Eddie Cabot (Chris Penn) and Joe Cabot (Lawrence Tierney) walk, George Baker’s “Little Green Bag” sets the music. This makes everything cooler – the sunglasses, the defiant looks, and the almost uniformed suits that the thieves wear.

Just like a dream that’s going to turn into a nightmare in just a few seconds, the slow motion scene in “Reservoir Dogs” operates as contrast point about what is going to happen next – namely, violence, chaos, murder and betrayal.

4. La Belle et la Bête (1946)

When filmmakers say that making a movie sometimes feels like producing a miracle, it’s likely that Jean Cocteau’s “La Belle et la Bête” is the best example that anyone can give in that regard. This is because the film was shot just months after the World War II. The difficulty of getting film stock right after the war, along with the worn-out cameras that the crew had to use, justifies this statement.

After Belle’s father (Marcel André) grabs the rose his daughter (Josette Day) asked for, La Bête (Jean Marais) appears. Instead of killing him, La Bête proposes that one of his daughters can take his place. When Belle arrives into the mansion of La Bête, an entrance of pure poetry is delivered.

The mansion of La Bête is ornamented with limbs and parts of bodies of human beings. Everything is animated. The magic candelabras are arms that illuminate the house in function with the movement of the people inside who walk through its corridors. The statues have real eyes that seem to spy on every event that occurs within the walls of the building. The result is a display of elegance and grace that enhance the film’s poetic tone.

3. Antichrist (2009)

The beginning of “Antichrist” presents an unnamed couple, He (Willem Dafoe) and She (Charlotte Gainsbourg), having passionate sex while Georg Friedrich Händel’s “Lascia Ch’io Pianga Prologue” musicalizes the intense moment. Their son, careless, walks through the house and takes a chair to climb onto a table. Outside it’s snowing and an open window unleashes a disaster.

This scene is all about contrast. On one side, the powerful unsimulated sex that the unnamed couple has; on the other side, the imminent death of their toddler. These actions depict, in a sense, both the origin and the end of life by constructing a hypnotic rhythm that lingers aggressively in the audience’s mind.

In “Melancholia,” the follow up to “Antichrist” in the “Depression Trilogy,” a similar slow motion scene it’s performed. In that case, the subtlety of the scene is embellished with Richard Wagner’s “Tristan und Isolde.” It seems that Lars von Trier loves to decorate humanity’s inner darkness with a dress of irresistible grace.

2. A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Paul Thomas Anderson stated once, “It’s so hard to do anything that doesn’t owe some kind of debt to what Stanley Kubrick did with music in movies”. In the case of “A Clockwork Orange,” the use of Rossini’s “The Thieving Magpie” just adds so much to the slow motion movement the actors portray. In a way, it feels inseparable from the scene itself.

After the droogs express doubts about the scope of the gang’s crimes, Alex DeLarge (Malcolm McDowell), hurt by the questioning of his authority, decides to beat its team in the “Thamesmead South Housing Estate” in London in a really comic yet violent slow motion scene known as the “Flat Block Marina” scene.

Alex is clearly the leader of the gang. The rest of the droogs fall into the water in a very humiliating way. The use of slow motion could be interpreted both as confirmation of his authority, and as public embarrassment made to punish his crew.

1. The Matrix (1999)

The bullet scene of “The Matrix” is a timeless piece of action filmmaking. Over the years, it has become perhaps the most iconic scene of the movie. The classy movement of Neo (Keanu Reeves) dodging bullet will remain forever in the audience’s mind when they remember “The Matrix.”

John Gaeta, the special effects supervisor, claimed that the he found inspiration in Michel Gondry’s use of a technique called view-morphing to create the “Bullet Time” effect. “Bullet Time” enabled a shot to advance in slow motion, while the camera seems to move through the scene at a normal pace.

The result of this particular special effect illustrated the power that the characters had with regards to space and time. John Gaeta said, “A visual analogy for privileged moments of consciousness within the Matrix.”