10. Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927)

F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans is a staggering accomplishment and one of the very finest of the silent era. The plot is uncomplicated and unabashedly romantic — wife (Janet Gaynor) versus mistress (Margaret Livingston), bustling city versus bucolic country — but the birsk and ready camera never rests.

Crammed with cinematic innovations and never before seen cinematography courtesy of Charles Rosher and Karl Struss (particularly powerful are the film’s numerous tracking shots which combined so much of Murnau’s signature style; forced perspective, miniatures, sets of varying sizes and matte paintings, all to dizzying effect).

No one during the silent era could capture and proclaim animative dreamscapes quite like Murnau. “Sunrise conquered time and gravity with a freedom that was startling to its first audiences, to see it today is to be astonished by the boldness of its visual experimentation,” enthused Roger Ebert, adding; “Murnau was one of the greatest of the German expressionists.”

Cahiers du Cinema has called Sunrise “the single greatest masterwork in the history of cinema”— and that only seems like hyperbole if you’ve never seen this shimmering standard.

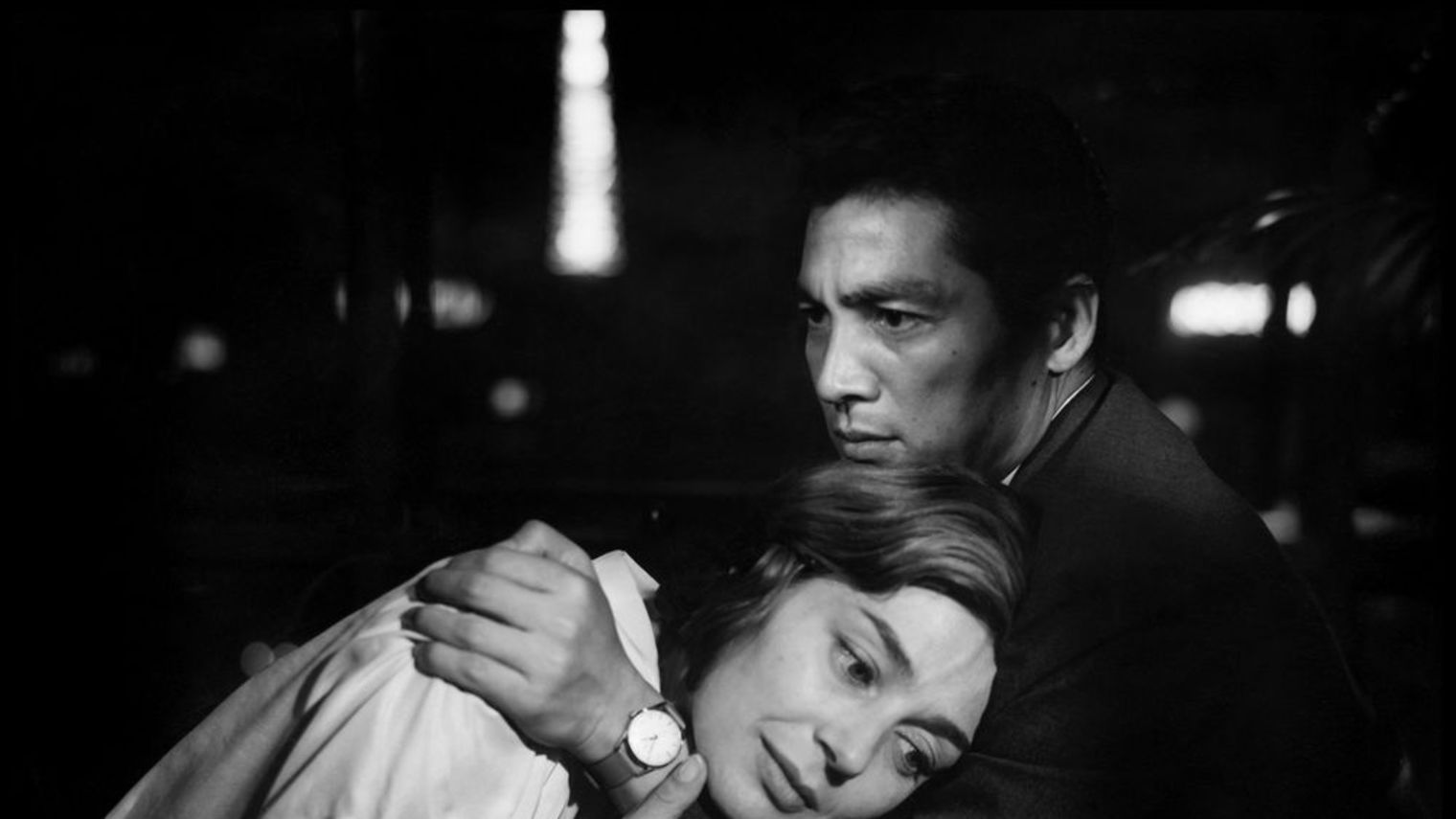

9. Hiroshima, Mon Amour (1959)

“The most beautiful film I’ve ever seen” raved French New Wave icon Claude Chabrol (Le Beau Serge, La Cérémonie) of Alain Resnais’s 1959 arthouse hit and feature length non-documentary debut. How enticing it is to consider and suppose that the cinema of the subconsciousness and of memory barely held breath before Resnais intimately accepted the subject matter with fascinating affection in his monumental Hiroshima, Mon Amour. As a restoration of romance and surrealism on screen Resnais’s debut stands nonpareil with the ability to shock and impair audiences with its innovations, its repentance, and its tenderness.

Resnais’s film begins in the summer of 1957, in Hiroshima. Here we meet a French actress from Paris, we never learn her name, but Emmanuelle Riva’s performance is one for the ages. In the city of Hiroshima, Riva’s actress is making a film and it is here that she meets a Japanese man, an architect, also nameless, played with sentiment and ascendancy by Eiji Okada.

The two come together and drift through Japan in an elliptical, time-twisting miasma of memory and yearning, with a burning in their marrow. Their affair is tiny and delicate, like a pink baby bird, too small to soar. Ad interim the desolation and post-apocalyptic shadow of 1945’s nuclear bombing and the spectre of a lover lost in German occupied France, making for them a death shroud.

The doomed cross-cultural romance of the leads – both have families far away, spouses, kids – made fireworks for late 1950’s audiences. That the film took such a strong anti-nuclear stance and juxtaposed images of intimacy with bodies of burn victims, did much to court controversy in its day and the images still shock and shake audiences to this day.

To love cinema, it is fair to say, is to love Resnais’s magnanimous entrée, an authentic dissertation on tenderness, cruelty, and forgetting.

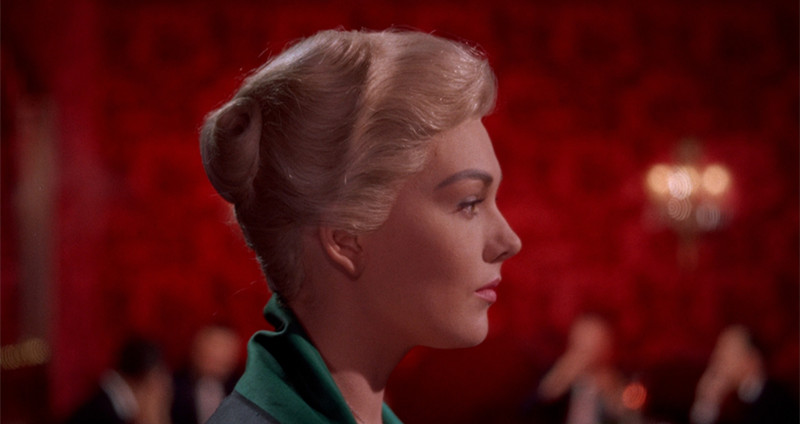

8. Vertigo (1958)

The chimeric use of color––has green ever depicted desolation and jealousy more succinctly?––adds to the tenacity and breadth of vision in Vertigo, often dubbed the most personal of Alfred Hitchcock’s films.

James Stewart is brazenly cast against type as John “Scottie” Ferguson, essentially an anti-hero, he only seems capable of associating with the world via his twisted and unhealthy obsession with a woman (Kim Novak) who is illusory––an inception meant wholly to entice him. After her death Scottie happens upon her double and degenerates into a controlling brute, a captive to his awful nature, and a slave to his unsound desires.

Hitchcock boldly reveals the nature of Novak’s dual roles as Judy and Madeleine early on in the film––though Scottie is left on the hook for quite a while––eschewing what 1950’s audiences would expect from a suspense thriller narrative, and the rich color spectrum visited upon the film add surreal layers that caught audiences off guard.

Perhaps Martin Scorsese put it best; “Whole books could be written about so many individual aspects of Vertigo –– its extraordinary visual precision, which cuts like a razor to the soul of its characters; it’s many mysteries and moments of subtle poetry; its unsettling and exquisite use of color; and its extraordinary performances…” Vertigo is clearly a monumental and illustrious work from a master of the craft.

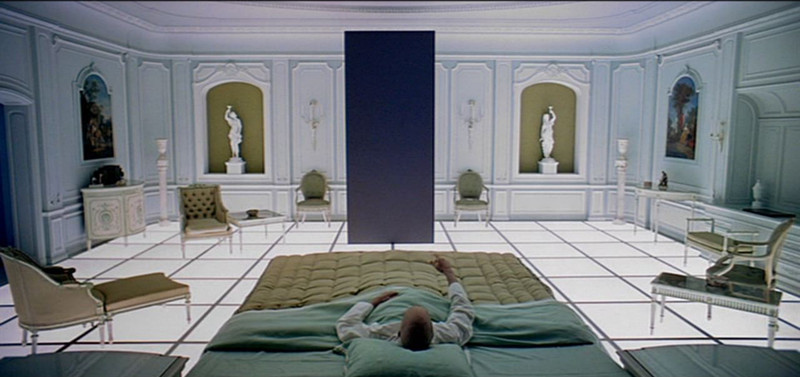

7. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

“[With 2001] I tried to create a visual experience,” offers director Stanley Kubrick, “one the bypasses verbalized pigeonholing and directly penetrates the subconscious with an emotional and philosophical content.” Divided into three distinct episodes, 2001: A Space Odyssey, arguably Kubrick’s crowning work, he describes and details the emergence of new forms of existence as witnessed by an alien intelligence in the form of a brunet hued monolith.

Part one depicts the development from primate to man—no dialogue is spoken, nor is it needed—part two is the rise from artificial intelligence to sentience, and part three is the transition from humanity to something outside our territory, a star child, a new evolutionary leap.

While 2001 does contain many memorable sequences with excellent dialogue, the film is bookended with lengthy dialogue-free passages, deeply psychedelic and bolstered substantially by György Ligeti’s music and eye-popping visuals.

There’s probably no other film in cinematic history that so skilfully combines arthouse integrity with populist prestige. Formally untouchable, technically immaculate, and artistically overwhelming, 2001 is the finest science-fiction film ever made.

6. Night of the Hunter (1955)

Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter is a whirling pictorial dervish, as well as a beautiful traumatic fable about a brother and a sister. Set in the Dust Bowl era, America is in the clinches of the Depression, but this here is no history lesson. No, this is a tale of two children, weakened and pursued by hysterical religiosity and the ignorance of the adult world.

Clearly a work of awe and evil, of enchantment and horror, The Night of the Hunter is one of those unshakable cinematic experiences that was misunderstood in its day but in the years since has been declared a masterwork.

An opiate-addled fairytale for grown-ups from the perspective of off-course and unloved children, Laughton together with legendary cinematographer Stanley Cortez (The Magnificent Ambersons, Shock Corridor), strove for and achieved a merger of German Expressionism and Film Noir composite.

The results? It’s a work that is overflowing with high-contrast, jagged angles, strange shadows, distorted perspectives, and startling, surrealistic sets. The resulting distortion of reality works flawlessly to exaggerate the emotional onscreen experience.

The plot is simple; “Reverend” Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum) is a religious fanatic who becomes a full blown serial killer who targets the widow (Shelley Winters) of a petty thief he did some time with. Soon Willa’s two children, John (Billy Chapin) and Pearl (Sally Jane Bruce) must escape Harry before it’s too late.

Thick with nocturnal panic, The Night of the Hunter preys on things like our childlike fears of the dark, and the adult assertion of cruelty and persecution. Here a stolen doll becomes an emblem for innocence made absent, a riverside trek is bird-dogged by a deistic bully that further clouds the child’s-eye-view of a mature terrene that has lost its baby teeth. Will the first blush of dawn ever erase what the night has revealed?

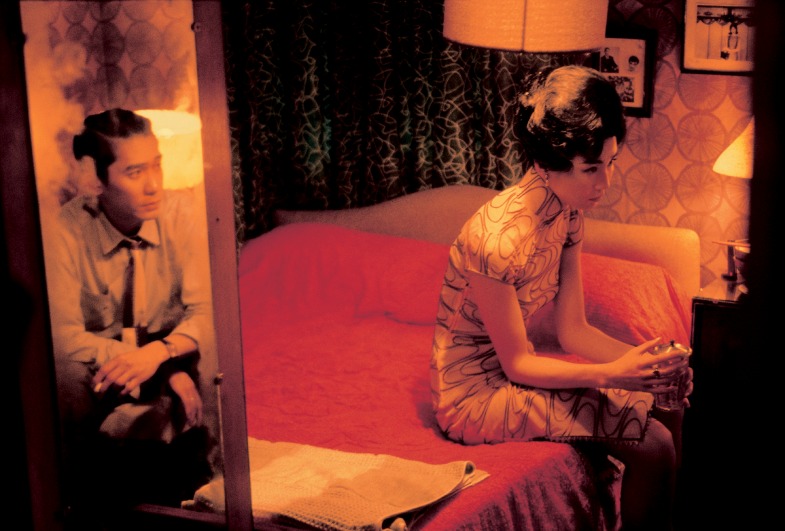

5. In the Mood for Love (2000)

The use of color, texture and light is integral to the ashen ache of stolen moments, and the often painful passage of time which hangs heavy upon Wong Kar-Wai’s 2000 masterpiece, In the Mood for Love. As anthem to the agony and ecstasy of close-lipped affection, this film more than any other in Wong’s considerable oeuvre, is a Proust-like conjuration of memory and misgiving.

In the Mood for Love unravels in Hong Kong, 1962, centering on two neighbors living in a close quarters tenement house. Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung shimmer as Su Li-zhen and Chow Mo-wan, the neighbors in question, who rightly suspect their respective spouses are having an affair.

A painful poetry and sad resignation haunt the pair of potential sweethearts, elegantly framed by superstar cinematographer Christopher Doyle, Wong’s frequent collaborator (and props also go out to Pung-Leung Kwan and Mark Lee Ping-bin, who also collaborate in lensing this film, due to the lengthy shooting schedule which pulled Doyle prematurely from the project). Numerous times the camera seems to pry, eavesdropping almost, on the star-crossed couple and their resisted romance.

The period details are perfect and never perfunctory—the cheong-san dresses adorned by Su Li-zhen are heart-stirring in detail and design—the color saturation and play of light is heavenly and mnemonic as is the use of music which conveys and captures an unfeigned nostalgia. The bright colors––the use of red adds a sensual and often smoky haze––and unconventional compositions that Wong’s name became synonymous with in the 1990s is here faultlessly fulfilled, even when hemmed in.

As close to perfection as possible, In the Mood for Love renders on an intimate scale the intersection of misery and euphoria, of romance in retrospect, and makes it into cinema’s saddest song of love lost to history.

4. Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

“One of the most literate and tasteful and exciting of expensive spectacles,” enthused Pauline Kael on David Lean’s most renowned picture, a film that to this day sets the high standards by which all epics are to be measured.

Based on the memoirs of enigmatic British officer T.E. Lawrence, Lean’s miraculously sun-soaked mega-production recalls the vaunted efforts to unite the Arab tribes against the Ottoman Turks during the backdrop of World War I.

Lawrence of Arabia made an instant superstar of Peter O’Toole, then a barely recognized face, as well as eloquently displaying the work of brilliant cinematographer Freddie Young (not to mention some stunning work from future director Nicolas Roeg as the film’s second-unit cinematographer).

One of Lawrence of Arabia’s most celebrated scenes memorably has Sherif Ali (Omar Sharif) emerging like magic on horseback out of the distant haze of the desert horizon, a tiny wavering speck that slowly grows into a man. Deservedly scooping up seven Oscar wins (including Best Picture, Director, Cinematography and Score [Maurice Jarre]). Take no prisoners in deed.

3. The Mirror (1975)

“[Andrei] Tarkovsky is for me the greatest,” said Ingmar Bergman, “the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream.”

Tarkovsky’s cinema is one of powerful apocalyptic poetry, of moral, religious, and spiritual questing, and one populated with breathtaking feats of technical skill. Long takes and tracking shots seem to last forever, muted colors and artfully expressive monochrome treat the viewer to unforgettable imagery and dreamy landscapes lost to brume and ruin. The Mirror offers up an idiosyncratic history of twentieth-century Russia, via a poet’s fragmented recollections on three generations of his family.

The poems used in The Mirror were each written and read by Arseny Tarkovsky (the filmmaker’s father) and Tarkovsky’s mother appears in a bit part as the protagonist’s aging mother. It’s no wonder that filmmaker and Tarkovsky scholar Amnon Buchbinder describes The Mirror as “Tarkovsky’s central film, and his most personal one,” going on to say that the film “achieves something which is uniquely possible in cinema but which no other film has even attempted: it expresses the continuity of consciousness across time, in a flow of images of the most profound beauty.”

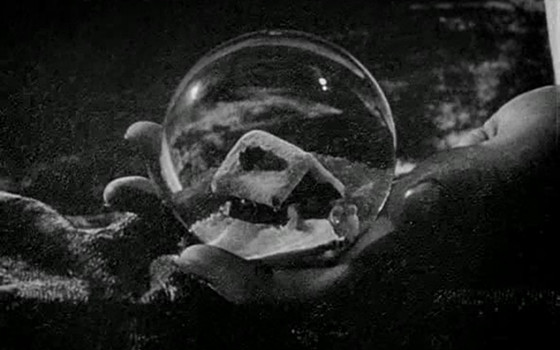

2. Citizen Kane (1941)

Easily the most innovative studio picture of its time, and the most visually astonishing black-and-white movie from the Golden Age, Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane changed cinema for the betterment of all and, from a technical aspect at any rate, has aged incredibly well.

“[Citizen Kane’s] style,” wrote the Sunday Times critic Dilys Powell in 1941 “was made with the ease and boldness and resource of one who controls and is not controlled by his medium.”

Co-written, starring, and of course directed by Welles (at the tender age of 25!), and filmed in secrecy to preempt any legalese that might block production (the film was based on real-life newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst), Citizen Kane is a legendary cinematic spectacle for a number of reasons, but of course for the means of this list we shall focus on the visual grandiosity and the legacy that resulted from that.

Time magazine detailed that “[Citizen Kane] has found important new techniques in picture-making and storytelling,” and arguably the most inventive technical aspect of the film is the extensive use of deep focus; for nearly every scene of the film finds the foreground, background, and the spaces in between in crisp, sharp focus.

Welles’ brilliant director of photography, Gregg Toland (“the best director of photography that ever existed,” Welles espoused on numerous occasions) pulled off all of this cutting-edge deep focus mastery via experimentation with lenses and lighting. But Toland’s and Welles’ R and D didn’t end there. They utilized other unorthodox methods including frequent and very impressionistic low-angle shots, creating something of a novelty as upward shots were rarely seen and never in such profusion (this was mainly because studios in Hollywood lacked ceilings because lights and sound gear occupied such spaces).

The influential French film critic and theorist André Bazin, who also co-founded the legendary Cahiers du Cinéma has proudly asserted that Welles created a revolution in filmmaking and that Citizen Kane is a sterling example of this. Bazin claimed that Welles’ Citizen Kane constituted “a dialectical step forward in film language.”

Let’s leave the last word on Citizen Kane for now with one of Welles’ great contemporaries, Erich von Stroheim, who said; “Whatever the truth may be about it, Citizen Kane is a great picture and will go down in screen history.”

1. Days of Heaven (1978)

Emerging from the New Hollywood wave of American filmmakers of the mid-to-late 1960s to the early 1980s, Texas-born auteur Terrence Malick is regularly referred to as “transcendental poet”, “uncompromising”, and “nonconformist”. With a film like his masterful Days of Heaven, for instance, audiences are truly given a work of artifice and stunning grace.

Utilizing two cinematographers (Néstor Almendros and Haskell Wexler) and inspired by the light, stillness and textures of Andrew Wyeth’s oil paintings and shot almost entirely during “magic hour”––at great effort for all involved––the results are absolutely ravishing. Through rolling fields of tall grass the indivisibility of man, nature, and even God amounts to something not unlike cinematic ecstacy.

Set in the 1910s, Days of Heaven stars Richard Gere as Bill, a Chicago steel worker on the lam with his sweetheart Abby (Brooke Adams) and his precocious teenage sister Linda (Linda Manz), who is also the film’s raspy and sometimes salty narrator. Finding refuge, for a time, in the swaying Elysian wheat fields of the Texas Panhandle, our leads are hired as seasonal harvesters by an ailing farmer (Sam Shepard)—who falls hard for Abby, believing her to be Bill’s sister.

Recipient of the Best Director at Cannes, Days of Heaven is a hushed, impressionistic, passion play and may well be the loveliest, slowburn cinema experiences you’ll ever endure and embrace. Don’t miss it for the world.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.