14. A Brighter Summer Day (1991)

Utterly immersive, and a delight from first frame to last, Edward Yang’s nearly four hour A Bright Summer Day is, as A.O. Scott so wonderfully puts it: “One of those movies that, by slow accretion of detail and bold dramatic vision, disclose the structure and feeling of an entire world.”

Set in 1960’s Taiwan during a single school year in bustling Taipei, a young boy will experience his first love amongst a dozen or so other characters (many of whom are non actors who give honest, anti-Hollywood performances), all under Yang’s patient, passionate, and serene direction.

Favoring the long take and the static camera over the close-up or a swooping dolly, Yang’s wonderfully gifted cast of amateurs display a startling and convincing emotional range in what’s regularly considered to be the high point of the Taiwanese New Wave. Rarely is storytelling this sweeping and provocative.

“Here, Yang has erected a temporal experience […] that few artists in any medium could ever hope to do,” writes indieWIRE’s Christopher Bell, adding: “If you love cinema, you’ll love this movie. That’s a promise.”

13. Flowers of Shanghai (1998)

“Our lives are full of fragmentary memories,” said Hou Hsiao-hsien of his films, in a recent interview. “We can’t give them names, we can’t classify them, and they have no great significance. But they lodge in the mind, somehow unshakeable.”

Unspooling in 1884, Flowers of Shanghai takes place in four elegant brothels (called “flower houses”), this innovative and incredibly beautiful film, is often considered to be Hou’s most visually sumptuous picture. Glacially-paced, often hard to follow, but always easy-on-the-eyes, Flowers of Shanghai recounts interweaving stories of love, loyalty, and deceit.

A film for lovers of the slow cinema movement, great patience is required. Many takes run upwards of seven to ten minutes without a cut, the cinematography is painstakingly precise, even breathtaking. The tableaus often read like lushly detailed murals, seducing the viewer, pulling them slowly downstream as if in a drug-induced daydream. Rich rewards await those with the attention span to appreciate them, and that’s not a dig. Hou’s films aren’t for everyone but they may be for you. Give him a try, you might like what you find.

12. Dreams (1990)

This artfully imaginative Japanese production, written and directed by the legendary Akira Kurosawa, presents a series of eight vignettes steeped in magical realism and inspired by the reoccurring dreams of its creator.

Made somewhat at the behest and with the assistance of Kurosawa super fans George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, and Martin Scorsese (who appears in one of the segments as Vincent van Gogh), Dreams is an inventive experience with powerful environmental themes.

“At 80, Kurosawa […] is impatient with artifice; He has long been a master of complex narrative,” wrote Richard Schickel in a 1990 piece for Time Magazine entitled “Night Tales, Magically Told”. Schickel continues: “Now [Kurosawa] wants to tell what he does. There are no wild juxtapositions of the creatures of his sleeping world with the images of his waking world. They are, after all, products of the same sensibility. The rhythms of his editing and his staging are serene – hypnotically so. To be able to do so, we need to know what is going on. And this is one of the most lucid dreamworks ever placed on film.”

11. Sátántangó (1994)

Filmed and artfully framed in gorgeous black-and-white, Bela Tarr’s overlong opus, Sátántangó is, as Susan Sontag suggested, “devastating, and enthralling for every minute of its seven hours.” Though putting the daunting runtime aside, Sontag did famously conclude that she’d be happy “to see it every year for the rest of my life.”

An epic runtime is always a hardsell, to be sure, but Tarr’s episodic study of the denizens of a small Hungarian village grappling with the effects of the fall of Communism is a course in artistic vision and license. Long takes, and shots that frequently last around the 10 minute mark (including a great number of elegantly framed dance sequences with a completely static camera), it’s certainly the type of film to both test and reward the most patient amongst us.

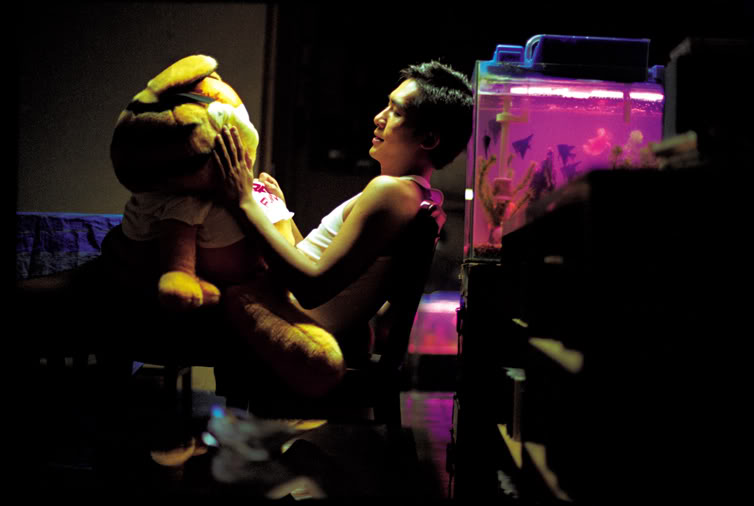

10. Chungking Express (1994)

Wong Kar-Wai’s ecstatic romantic comedy drama casts C-pop superstar Faye Wong in one of two impossibly energetic, color-saturated, and highly stylized stories. With a music video aesthetic, this vibrant, visceral film is also buoyed by its use of music (will Mamas and the Papas smash “California Dreamin’” ever be used to such glorious effect ever again?), adding the occasional clandestine dip into almost surreal reverie.

Chungking Express is hard to forget — romantic yearning and sacrifice both poignant and impassioned frisk with the facile uncertainties of youth and acquired wisdom — amounting to Wong’s first real masterpiece.

9. Dead Man (1995)

According to author and film critic J. Hoberman, “[Dead Man] is the Western Andrei Tarkovsky always wanted to make”, and considering the existential, post-modernist, and apocalyptic statements issued in Jim Jarmusch’s film, Hoberman speaks unadulterated truth.

Using his signature minimalist and informed style, Jarmusch cast Johnny Depp in the title role as William Blake, a visitor to the Western frontier, who also, cruelly, isn’t long for this earth. Depp’s Blake is a deliberate literary allusion to the 18th century poet — a repeated reference is that Blake’s poetry exists in the bullets of his gun — and Dead Man cascades such suggestion.

Reluctantly partnered up with a Native American named Nobody (Gary Farmer), a Virgil to Depp’s Dante, they embark on a funerary dirge that won’t end in their favor. Dead Man offers an inspired list of crazy cameos (including Billy Bob Thornton, Robert Mitchum, and Iggy Pop), a riveting score by Neil Young, and more perversely, an unconventionally damnable treatment of capitalism, racism, and cinematic violence. The darkest, most shocking film in Jarmusch’s oeuvre, it’s also his most far-reaching.

8. Safe (1995)

An existential art house horror movie, writer-director Todd Haynes’s Safe coolly details the catastrophe that awaits a Los Angeles woman, Carol White (Julianne Moore, brilliant), who’s allergic to her own environment. A masterpiece of detached uncertainty and creeping dread, Safe is also one of the best American films of the nineties.

Carol is a So Cal housewife in the year 1987, where she leads a humdrum life in a sober suburban façade that slowly starts to languish around her. She has lifeless sex with her addled husband (Xander Berkeley), she shops, and gossips, and has hair appointments, and her comfortable existence crashes down bit by bit.

The horror of Haynes’s film rests amidst the anxiety in Carol’s day-to-day life, her disconnect with her family, and her inability to function. Haynes shows an at times Kubrickian sense of spacial dynamics, occasionally throwing back to 1970s paranoia thrillers (think the Conversation [1974], Marathon Man [1976], and the Parallax View [1974]), and evidence of an Antonioni-like woman in distress vibe (Il Deserto Rosso [1964] specifically), yet still retaining his own inventive modes and manipulations.

As an exercise in visual style, Haynes proves his mastery with Safe, a film that demands a clear-sighted measure from the viewer. It hints at slow cinema with its persistent use of master shots, and it makes for a prime example of chic postmodernist cool. He allows his carefully composed shots to linger, to escalate, to alienate, resulting in a captivating and controlled patchwork that wavers to the diligent viewer’s whim.

Ultimately with Safe, Haynes presents a somnambulant nightmare of consumerist decay, of a woman’s life leeched of vitality, secure only in the knowledge that something is terribly, terribly wrong.