17. Bicycle Thieves (1948)

Deceptively simple and emotionally powerful, Vittorio De Sica’s beloved masterpiece is perhaps the most famous Italian film ever made and is the definitive work of Italian neorealism.

Receiving a special 1949 Oscar as “Most Outstanding Foreign Film”, Bicycle Thieves has been called “surely the most universally praised movie produced anywhere on planet earth during the first decade after WWII” by Village Voice critic J. Hoberman.

Antonio Ricci (Lamberto Maggiorani, superb) is a long-unemployed worker who finally lands a much-needed job as a municipal bill poster, only to have the bicycle he needs for the position stolen from under him. Setting out with young son Bruno (Enzo Staiola, a revelation) to look for the missing bike, their desperate searching amidst Rome’s poverty-stricken streets is a modern-day Odyssey wherein the best and worst aspects of human nature are harshly revealed.

The neorealism movement’s founder and chief theorist Cesare Zavattini (who wrote Umberto D. amongst other films for De Sica) provides the script, and the film was effectively and famously shot on location using an impressive cast of non-professional performers.

A massive international hit and an important film by any measure, Bicycle Thieves has, a stunning 70 years on, lost none of its power or its ability to move audiences.

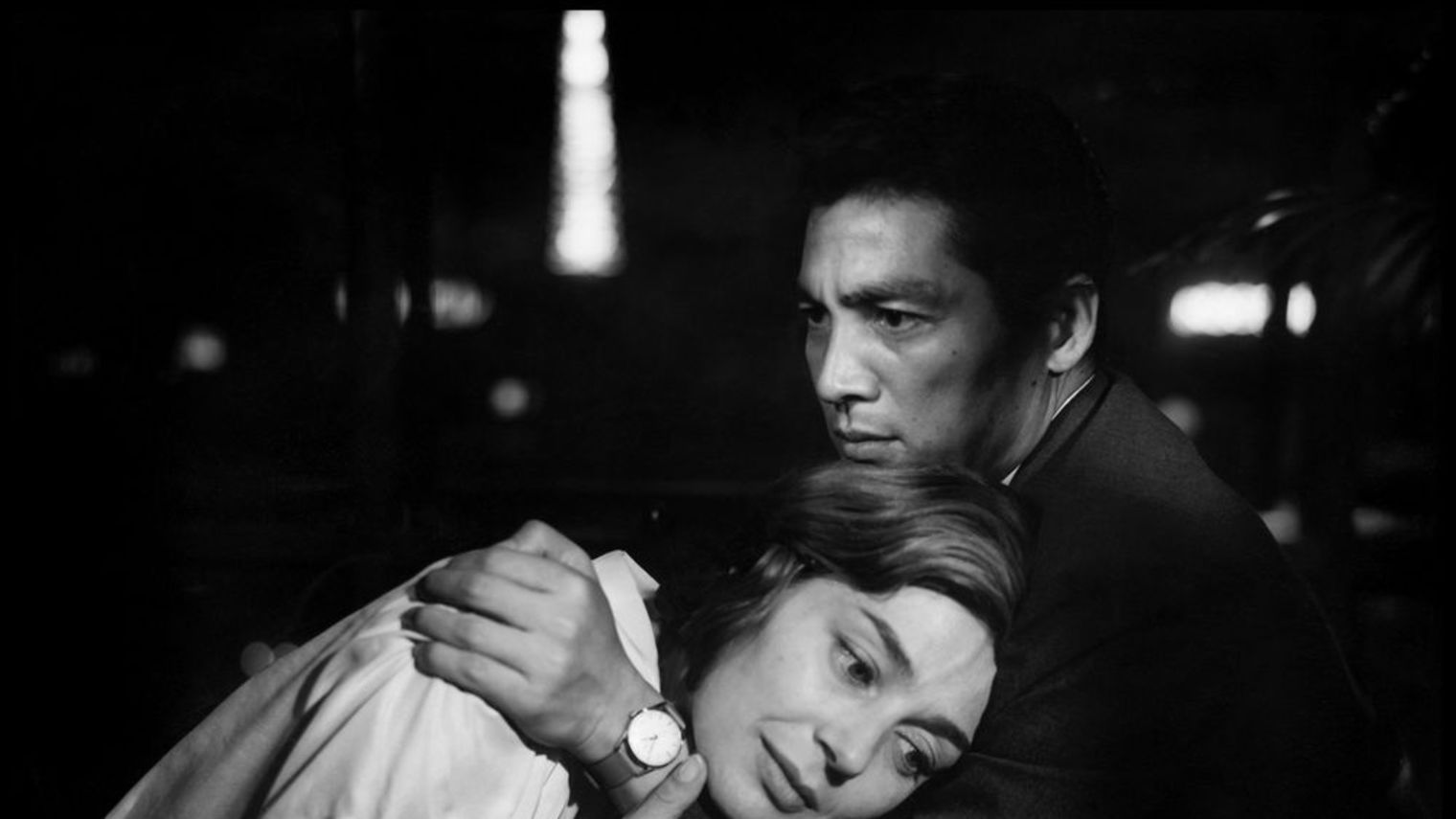

16. Hiroshima, Mon Amour (1959)

“The most beautiful film I’ve ever seen” raved French New Wave icon Claude Chabrol (Le Beau Serge, La Cérémonie) of Alain Resnais’s 1959 arthouse hit and feature length non-documentary debut.

How enticing it is to consider and suppose that the cinema of the subconsciousness and of memory barely held breath before Resnais intimately accepted the subject matter with fascinating affection in his monumental Hiroshima, Mon Amour. As a restoration of romance and surrealism on screen Resnais’s debut stands nonpareil with the ability to shock and impair audiences with its innovations, its repentance, and its tenderness.

Resnais’s film begins in the summer of 1957, in Hiroshima. Here we meet a French actress from Paris, we never learn her name, but Emmanuelle Riva’s performance is one for the ages. In the city of Hiroshima, Riva’s actress is making a film and it is here that she meets a Japanese man, an architect, also nameless, played with sentiment and ascendancy by Eiji Okada.

The two come together and drift through Japan in an elliptical, time-twisting miasma of memory and yearning, with a burning in their marrow. Their affair is tiny and delicate, like a pink baby bird, too small to soar. Ad interim the desolation and post-apocalyptic shadow of 1945’s nuclear bombing and the spectre of a lover lost in German occupied France, making for them a death shroud.

The doomed cross-cultural romance of the leads – both have families far away, spouses, kids – made fireworks for late 1950’s audiences. That the film took such a strong anti-nuclear stance and juxtaposed images of intimacy with bodies of burn victims, did much to court controversy in its day and the images still shock and shake audiences to this day.

To love cinema, it is fair to say, is to love Resnais’s magnanimous entrée, an authentic dissertation on tenderness, cruelty, and forgetting.

15. Pather Panchali (1955)

“[Pather Panchali is] a masterpiece, inarguably…” wrote Village Voice scribe J. Hoberman, adding that the film is “the last masterpiece of neorealism.”

An absolutely unforgettable debut, Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali burst upon the scene as a revelatory bombshell introducing audiences to a previously unknown national cinema. Adapting a renowned autobiographical 1929 novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, Pather Panchali is the first in the Apu trilogy, the coming-of-age tale of brother (Apu [Subir Banerjee]) and sister (Durga [Uma Das Gupta]), two children growing up in a poverty-stricken Brahmin family in rural Bengal.

Recounting with nuanced eyes their formative encounters with the heartbreaking sorrows, ecstatic joys, and the humbling mysteries of life, Ray invests ordinary life events with extraordinary poeticism and greatly compassionate power. Pather Panchali is a stunning work of sublime simplicity, beauty, and lyricism, and underscoring Ray’s two key influences: the stylistic directness of Italian neorealism and the humanism of Jean Renoir. The film’s score by Ravi Shankar is also something of a revelation.

14. Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972)

Roger Ebert called Werner Herzog’s towering 1972 film Aguirre, the Wrath of God “…one of the great haunting visions of the cinema,” and in a retrospective review of the film The Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw dubbed it as “one of the great folies de grandeur of 1970s cinema, an expeditionary Conradian nightmare like Coppola’s Apocalypse Now.”

A grand achievement from Herzog, and his first film with muse Klaus Kinski, Aguirre, the Wrath of God is a fever dream journey into the inky void of humanity’s core, the fabled “Heart of Darkness.” Gorgeously lensed by Thomas Mauch in the Peruvian jungle, the film unspools during Pizarro’s 1560 exploration of the Amazon as a small reconnaissance party, utterly doomed, sets off in search of the legendary Inca city of gold, El Dorado.

Already a mutinous madman, Aguirre (Kinski, brilliant) swiftly proclaims himself the titular “Wrath of God” and resolves to breed a new, purer, more perfect race of man.

As an allegory of both Nazism and Vietnam while thumbing his nose at the arrogance of “civilized” society and the capitalistic greed of the conquistadors, every frame of this film is custom fit to astonish and often overwhelm the viewer. Miss it at your own peril.

13. La Dolce Vita (1960)

Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita is not only one of the key films in his considerable canon, it marked a new phase in his career, kicking off a cycle of ambitious, autobiographical, episodic, self-conscious and visually rich works that elevated his stature as a cinematic artist while coining the term “Felliniesque” at the same time.

Starring Marcello Mastroianni in his most recognizable role, La Dolce Vita paints a vivid panoramic portrait of Rome in all her contemporary decadence; a place of pushy paparazzi, promiscuous sex, and endless partying.

Co-starring Anita Ekberg in an iconic turn as Sylvia, the latest Hollywood sex goddess, removed from Tinseltown to Italy to star in a Biblical epic.

La Dolce Vita’s vision of Rome is a phantasmagoria of contradictions: the sacred and the profane, the material frisking with the spiritual, the Christian and the pagan. The film was a great succès de scandale in the early 1960s; the Vatican denounced it as disgusting and immoral, and famously even Fellini’s mother was reported to ask her prodigal son, “Why did you make such a picture?”

One of the film’s many champions, Pier Paolo Pasolini was so stuck by the audacity and daring of the film, saying that it was “[Fellini’s] and his alone… The camera moves and fixes the image in such a way as to create a sort of diaphragm around each object, thus making the object’s relationship to the world appear as irrational and magical.”

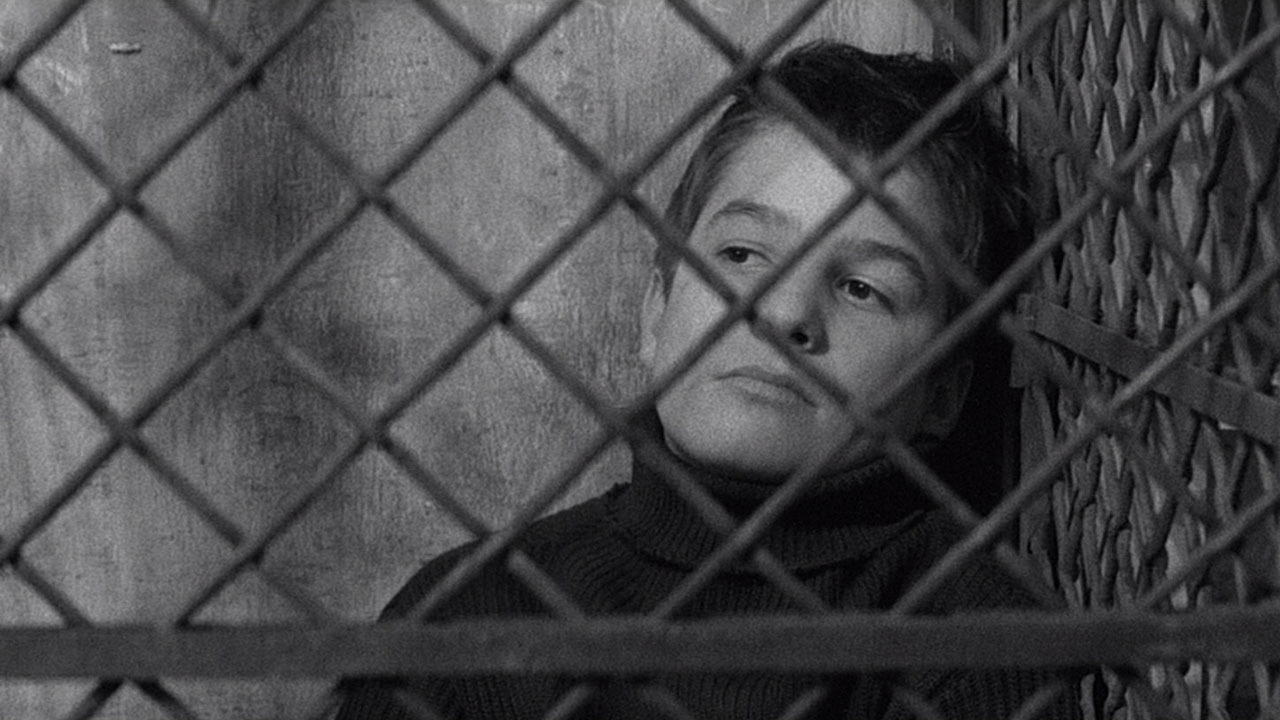

12. The 400 Blows (1959)

A very warm and very personal film and certainly one of cinema’s most celebrated debut films, as well as an early breakthrough of the French nouvelle vague, François Truffaut’s semi-autobiographical triumph, The 400 Blows offers one of the best portraits of adolescence ever filmed.

For Truffaut not only was the film a triumphant winner of Best Director honors at Cannes in 1959 (owing to his occasional notoriety as a film critic, he had been barred from Cannes the previous year for the ferocity of his Cahiers du Cinéma pieces), it was also something of a vindication.

Starring a very young Jean-Pierre Léaud — soon to be Truffaut’s go-to on-screen alter ego and muse — in a marvelous acting debut as Antoine Doinel, a troubled 12-year-old whose revolt against parents, school, and society at large will ultimately land him in a reformatory.

The first instalment in the director’s celebrated “Antoine Doinel Cycle,” which grew to include five films (each starring Léaud), The 400 Blows is still the yardstick in which all films of neglected youth in revolt and societal disarray must be measured, this is an unforgettable film and a remarkable snapshot of Paris during the 1950s.

11. Ran (1985)

“The physical scale of Ran is overwhelming,” wrote Gene Siskel in his original Chicago Tribune review, adding: “It’s almost as if [Akira Kurosawa] is saying to all the cassette buyers of America, in a play on Clint Eastwood’s phrase, ‘Go ahead, ruin your night’ — wait to see my film on a small screen and cheat yourself out of what a movie can be.”

A long-gestating passion project from a legendary Japanese filmmaker, Akira Kurosawa directed, edited, and co-wrote (along with screenwriters Masato Ide and Hideo Oguni) this powerful period tragedy, derived from both Shakespeare’s King Lear as well as incorporating legends of the daimyō Mōri Motonari (a 16th century Japanese ruler). Hailed by Kurosawa as “a series of human events viewed from Heaven”, Ran has also been praised ever since its release for the power and scope of its poetic imagery as well as its incredible use of color.

Starring Tatsuya Nakadai as Great Lord Hidetora Ichimonji, a seventy year-old Sengoku-period warlord who decides to abdicate and divide his domain amongst his three sons; the eldest, Taro (Akira Terao), will rule; his second son, Jiro (Jinpachi Nezu), and his third, Saburo (Daisuke Ryu) will take command of the Second and Third Castles but are expected to unquestioningly obey and support Taro. Soon Saburo defies the pledge of obedience and is banished, and despair and destruction will soon follow.

There’s so much to appreciate and marvel over during Ran’s two hour and forty minute run time (and it breezes by effortlessly), least of all being the gobsmackingly grand period detail and production design from Shinobu and Yoshirō Muraki; the gorgeous costume design from

Emi Wada (who deservedly won an Academy Award for Best Costume Design for her amazing efforts); and the thrilling trifecta of talented cinematographers (Asakazu Nakai, Takao Saito, and Masaharu Ueda).

10. Yi Yi (2000)

Edward Yang’s poignant family portrait, Yi Yi (A One and a Two) is a rich, rewarding, and unforgettable cinematic experience that spans three generations of a Taipei family. While the film certainly takes its time to unfold, it doesn’t waste a moment of its three hours run time, in what may be Yang’s most accessible and engaging film.

In contemporary Taiwan the lives of the Jian family are examined via the alternating perspectives of three family members; the father N.J. (Nien-Jen Wu), the teenage daughter Ting-Ting (Kelly Lee) and the photography-obsessed eight-year-old son Yang-Yang (a wonderful Jonathan Chang).

Unsatisfied with the direction of his current job at a failing computer company, N.J. attempts change as well as reacquainting with a woman (Ko Su-yun), a lost cause love interest from his distant past. Meanwhile Ting-Ting and Yang-Yang contend with the various trials of youth, all while tending to N.J.’s mother-in-law (Tang Ru-yun), who lies in a coma.

As in his previous work, Yang’s cast is populated almost entirely with non-actors, and the performances he elicits have an honesty and an impact lacking in this sort of moving melodrama. Yi Yi is in a class all by itself.

9. Jules et Jim (1961)

A bittersweet experience of lasting intensity, François Truffaut’s regret tinged showpiece, Jules et Jim, is anything but atypical in its telling of boy meets girl meets boy. A period romance rich in sweet, stinging sadness as Catherine (Jeanne Moreau) romances and ravages Jules (Oskar Werner) and Jim (Henri Serre), Jules et Jim was met with a 15-minute standing ovation at its premiere, this is Truffaut’s best-loved film for a reason, and perhaps no other film best captures the spirit of the French New Wave.

Adapted from Henri-Pierre Roché beloved semi-autobiographical novel from 1953, Jules et Jim, this lightning-paced foray into doomed love and exquisite sadness is a charming and influential film of giddy romance run amok. The spirited and extensive narration, which inspired Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990), amongst other modern works, was light years ahead of its time, as were the stylish freeze frames, jump cuts, and taboo-smashing ménage à trois/love triangle scenario.

Sure, certain aspects of the film may not have aged perfectly well, some of what made Jules et Jim such a groundbreaking pièce de résistance may not be readily apparent to modern audiences, but the film still carries a fresh and sunny élan, a buoyancy and fire as infectious today as it ever was. And the performances hold strong in this delicious and gratifying tour de force.