8. Stalker (1979)

Perhaps deceptively derived from Arkady and Boris Strugatsky great 1972 sci-fi novel of big ideas, “Roadside Picnic”, Stalker is an intuitive and uncanny masterpiece from Andrei Tarkovsky. Teeming with dense visual detail, Stalker unfolds some time after aliens have visited and left the Earth, as the novel details: “…leaving behind a number of artefacts of their incomprehensibly advanced technology. The places where such artefacts were left behind are areas of great danger, known as ‘Zones.’’

The film follows three men––the Writer (Anatoliy Solonitsyn), the Scientist (Nikolai Grinko), and the Stalker (Alexander Kaidanovsky)––as they journey through the Zones. It’s understood that somewhere within the Zones exists the Room, where wishes are granted, and where each man, dissidents, have a calling to enter. Is it self-discovery that awaits them in this offbeat and bizarro reworking of the Wizard of Oz via a Kafkaesque winnow?

“As always, Tarkovsky conjures images like you’ve never seen before,” raved Time Out’s Derek Adams, “and as a journey to the heart of darkness, it’s a good deal more persuasive than Coppola’s.”

There’s no denying Stalker’s complex and tilted narrative, and its deeply penetrating philosophical musings do, to a large extent, distance it from populist SF like Star Wars, but for the courageous cinéaste Tarkovsky presents deep, detailed, and far-reaching rewards. As allegory, fantasy, and treatise on art, science, and faith, nothing comes close to the daring ideas and insights Stalker limns. If Stalker isn’t thought of as a masterpiece then the word holds no meaning. Essential cinema.

7. The Grand Illusion (1937)

Pauline Kael rightly asserted that Jean Renoir’s La Grande Illusion is “one of the true masterpieces of the screen” as it represents not just one of film’s finest pacifist works, it also makes for a perceptive and penetrating inquiry into class loyalty and relations.

Set during the First World War, Renoir details for us three French POWs — an aristocratic officer (Pierre Fresnay), a Parisian mechanic (Jean Gabin), and a Jewish banker (Marcel Dalio) — all of whom are held in a prison camp under the command of an aristocratic Prussian, Captain von Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim).

The French officer and his German counterpart bond as they find a natural social affinity, but their friendship cannot take precedence over wartime duties and patriotism. Like Renoir’s later film Rules of the Game 91939), Grand Illusion is an exemplar of his much-admired humanism and, with its complicated ahead-of-its-time sequence shots, remarkably fluid camera movement, and impressive composition-in-depth (still staggering all these decades later), Renoir’s mastery of mise-en-scène aesthetics secures his title as a legendary filmmaker of incredible influence.

6. Seven Samurai (1954)

Akira Kurosawa (Rashōmon [1950]), who Steven Spielberg has described as “the pictorial Shakespeare of our time” made his most enduring samurai epic, Seven Samurai, in 1954, and it functions not unlike a classic John Ford Western — indeed it would be the basis for the gunslinging classic The Magnificent Seven (1960) — that has also stood the test of time as a ribald cultural crossover.

Sam Peckinpah (The Wild Bunch [1969]) once famously quipped: “I’d like to be able to make a Western like Kurosawa makes Westerns.”

Kurosawa’s classic concerns seven disgraced, and masterless samurai hired by an impoverished village to defend them against an evil band of outlaws who have been plaguing them for some time, ravaging their crops and instilling terror and panic as the severity of their crimes grow.

Amongst the eponymous seven samurai is their ronin master, Kambei Shimada, played magnificently by Takashi Shimura (Ikiru) and lion-hearted hanger-on Kikuchiyo, played by the legendary Toshiro Mifune (Yojimbo), who each redefine heroism on their own astonishing and unexpected terms. Also engaging is the rain-soaked final siege sequence, an energized miracle of black-and-white cinematography, breathtaking boldness and jaw-dropping action that even today, some sixty years on, remains unrivaled. An epic in every sense of the word.

5. L’Atalante (1934)

As beloved and cherished a film as you’re ever likely to find, Jean Vigo’s only feature is one of cinema’s most intoxicating, succinct and suggestive of masterpieces. A disarmingly simple and achingly sweet tale of loss and love, imbued with astonishing and artful poetry.

Juliette (Dita Parlo) is a hopeful young bride who joins Jean (Jean Dasté), her new husband, aboard his river-faring canal barge, the titular “L’Atalante.” The exciting adventures Juliette’s dreamed of prove to be ever elusive, and she must contend with a curmudgeonly first mate named Père Jules (Michel Simon), a dimwitted cabin boy (Louis Lefebvre), not to mention a herd of mangy cats.

Vigo’s wonderfully ethereal film evocatively weds realism and surrealism as it attains an infectious anarchic spirit. L’Atalante was famously (or rather infamously) mutilated by its distributors and was a commercial shipwreck upon initial release; it would be many years before the film received its due or could be viewed in a version matching Vigo’s original vision. But it did, and has been cause for celebration ever since.

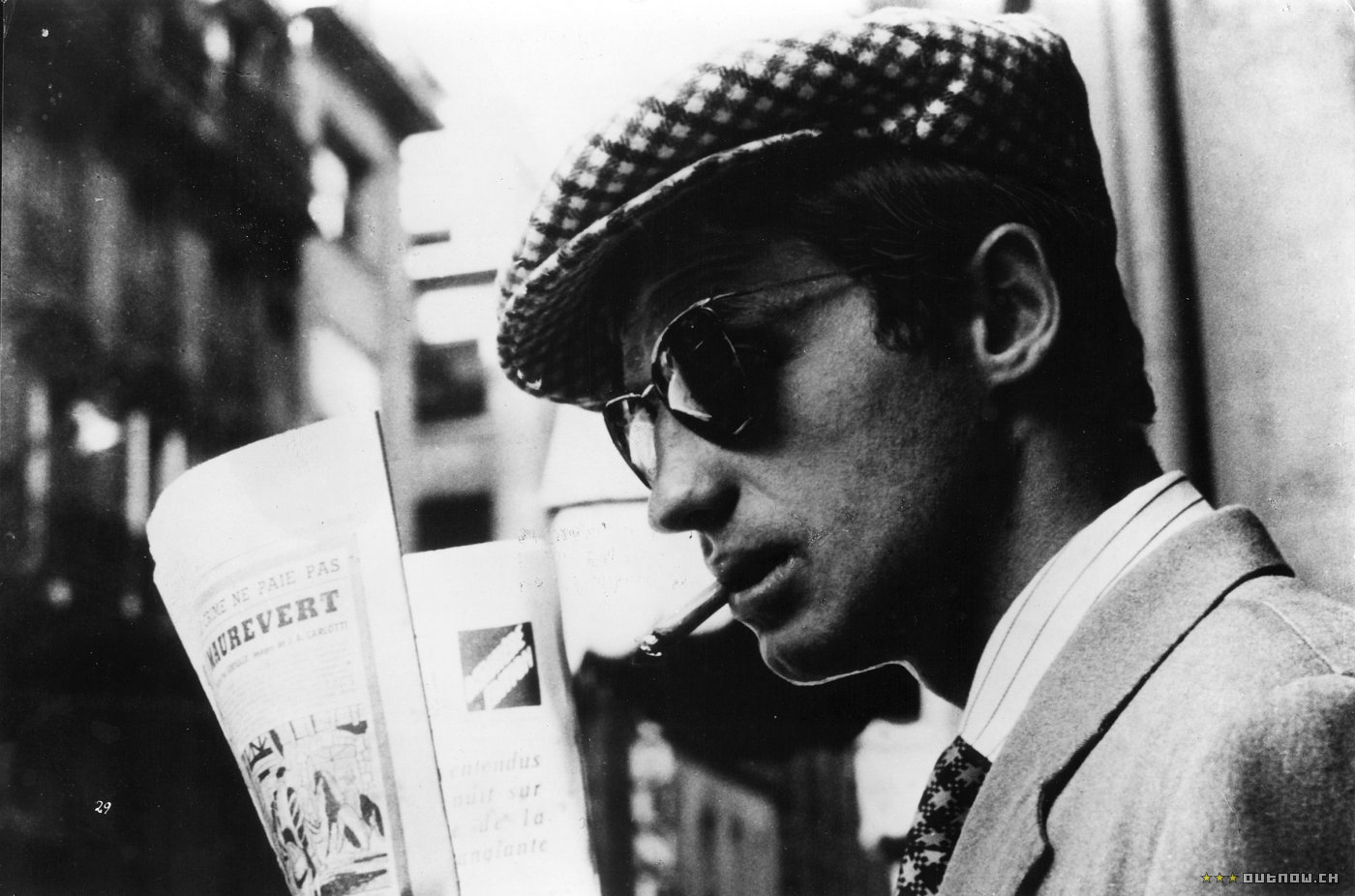

4. Breathless (1959)

“Modern movies begin here, with Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless in 1960,” raved an enraptured Roger Ebert, adding in his proximation that “no debut film since Citizen Kane in 1942 has been as influential.”

One of cinema’s watershed works, Godard, who is easily one of the most influential filmmakers of all time, gave the world Breathless, and in so doing simultaneously gave the French New Wave its most influential, imitated and well-valued movie of the 1960s.

At once a playful parody of and loving homage to the American gangster film, Breathless stars Jean-Paul Belmondo (in his breakout role) as Michel, a lovable small-time crook on the lam from the fuzz in Paris, and Jean Seberg as Patricia, his ambivalent American girlfriend in a role that would make Seberg a fashion icon.

Breathless’s slick use of handheld 35mm cameras, and location shooting would soon define New Wave aesthetics, as did much of its most radical technical innovation, the attention-snaring use of elliptical editing and the startlingly effective jump cut.

Overflowing with pop culture references, in-jokes aplenty, nods to other films both past and present, abrupt tonal shifts, and Brechtian asides (later to be known as Godardian asides, let’s face it), all that would be deemed New Wave hallmarks. As Sight and Sound put it, it was the movement’s “manifesto.”

In the decades since it debut Breathless has remained as engaging as ever, and as vital as ever, too, having revolutionized so much that followed after. Breathless is one of those films that makes it impossible to imagine the history of cinema without it.

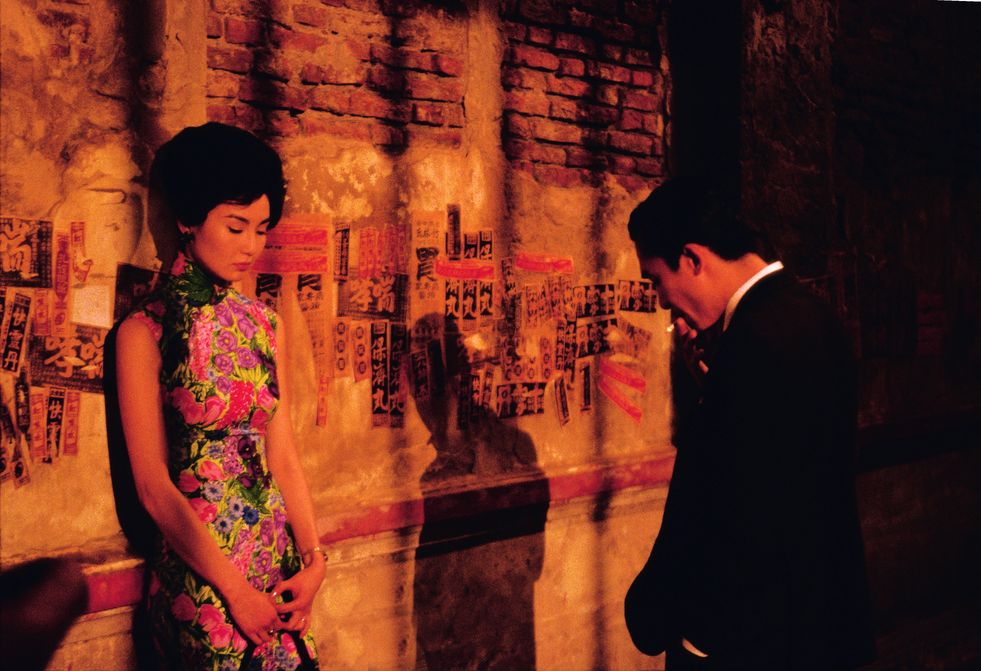

3. In the Mood For Love (2000)

The ashen ache of stolen moments, and the often painful passage of time hangs heavy upon Hong Kong filmmaker Wong Kar-Wai’s 2000 masterpiece, In the Mood for Love. As anthem to the agony and ecstasy of close-lipped affection, this film more than any other in Wong’s considerable oeuvre, is a Proust-like conjuration of memory and misgiving.

The second installment of a rather loose trilogy that began with Days of Being Wild (1990) and concluded with 2046 (2004), In the Mood for Love unravels in Hong Kong, 1962, centering on two neighbors living in a close quarters tenement house. Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung shimmer as Su Li-zhen and Chow Mo-wan, the neighbors in question, who rightly suspect their respective spouses are having an affair.

A painful poetry and sad resignation haunt the pair of potential sweethearts, elegantly framed by superstar cinematographer Christopher Doyle, Wong’s frequent collaborator. Numerous times the camera seems to pry, eavesdropping almost, on the star-crossed couple and their resisted romance.

The period details are perfect and never perfunctory — the cheong-san dresses adorned by Su Li-zhen are heart-stirring in detail and design — the color saturation and play of light is heavenly and mnemonic as is the use of music which conveys and captures an unfeigned nostalgia. The bright colors and unconventional compositions that Wong’s name became synonymous with in the 1990s is here faultlessly fulfilled, even when hemmed in.

As close to perfection as possible, In the Mood for Love renders on an intimate scale the intersection of misery and euphoria, of romance in retrospect, and makes it into cinema’s saddest song of love lost to history.

2. L’Avventura (1960)

Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura is an aloof and artful masterpiece of existential dread, ennui, alienation, and a missing woman who is never recovered.

The film opens with Anna (Lea Massari) and her friend, Claudia (Monica Vitti) in a villa outside of Rome. They are soon joined by a circle of friends including Anna’s beau, Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti), and soon en masse they all board a yacht bound for Lisca Bianca. Antonioni, an artist of great breadth, quickly shatters the expected three-part story structure when, at the close of the first act, Anna disappears without a trace.

Claudia and Sandro embark on a half-hearted search for Anna, more a grand gesture really, as neither seem capable of solving the mystery. Not only do they have little to go on, their jaded tendencies seem to stymie their advances (except perhaps their advances on one another). Their search becomes an impotent one, though one that unfolds with grace and understanding.

L’Avventura won Antonioni the Jury Prize at Cannes that year, and established Vitti as an icon of Italian cinema. So explicit and painterly was Antonioni’s canvas-like frames that he elevated pop art to high art.

The final image of the film is unforgettable; Sandro seated on a bench, leaning against Claudia, who stands over him, with the Stromboli volcano imposing itself upon them in the distance, cold and cruel. So profound is this end scene that it has struck a resonating chord with audiences the world over and Martin Scorsese famously said it was “one of the most haunting passages in all of cinema, Antonioni realized something extraordinary: the pain of simply being alive. And the mystery.”

1. Tokyo Story (1953)

Yasujirō Ozu’s Tokyo Story is a masterpiece of Japanese cinema, and one that regularly finds itself topping best of lists such as this the world over. And while the very relatable tale of the aging married couple Shūkichi (Chishu Ryu) and Tomi (Chieko Higashiyama), and their trip to visit their adult children in Tokyo is one of bittersweet aspirations, adult pain, and profound beauty, often the mastery of the film’s black-and-white photography is ignored.

Tokyo Story exemplifies Ozu’s distinctive camera style perfectly. His “tatami shot” is used to great effect—this is his signature shot wherein the camera is positioned lower than usual, as if the viewer were kneeling in prayer—often lending a subtle yet heroic perspective to the most average and mundane of genuflections.

It’s also been noted by critics and scholars that there is almost no camera movement whatsoever in Tokyo Story, and in keeping with Ozu’s stubborn aesthetic to rarely shoot masters, here the film frequently breaks the 180-degree rule of screen direction, deliberately crossing the axis and making continuity questionable to motivate a stronger, and subtler dramatic impact (the opening scene with Shūkichi and Tomi does this very effectively, setting a tone that reoccurs throughout the film).

A film that asks the viewer to accept a certain sadness and serenity to the human condition, that is not only enormously moving but deeply resonant.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.