17. Hard to Be a God (2013)

The long-gestating final film from Russian cinema heavyweight Alexei Gherman (1985’s My Friend Ivan Lapshin) spent decades in pre-production, was begun in 2000, filmed over a six year period, spent years after that in post-production, and was finally finished posthumously by Gherman’s son, and released theatrically in 2013.

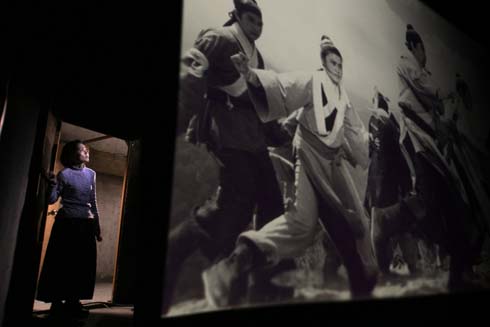

Hard To Be a God is that rare reward of visceral cinema, and an epic in every sense of the word. Adapted from the underground sci-fi cult novel by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky––the sibling duo who penned Tarkovsky’s Stalker––Gherman’s crowning achievement takes place on an alien planet Arkanar, eerily like our own only here the Renaissance never happened, resulting in a never-ending Middle Ages nightmare.

Shortly after I’d seen a wondrous 35mm print of Hard to Be a God at the Cinematheque in Vancouver, Canada, I had the good fortune to visit the Getty Museum in Los Angeles during an exhibit of Hieronymus Bosch’s work.

The medieval master’s unexpected imagery, dripping with macabre detail of hellish landscapes, fantastical and freakish figures, and startling religious narratives with cruel men and demonic beasts often adorned with halos or the twisted maws of damnation; here did I see with bracing clarity what Gherman and his gifted dual cinematographers Vladimir Ilyin and Yuri Klimenko were going for with Hard to Be a God.

Their richly detailed black-and-white cinematography recreates Bosch-like tableau and Brueghelian details of barbarity, beauty and grotesque human contest. If a more immersive, ingrained and extravagant film than this exists, I’ve yet to see it. Essential viewing for cinema lovers.

16. Far From Heaven (2002)

Todd Haynes’s first mainstream breakthrough came with this revisionist Douglas Sirk-style weepie from 2002, Far From Heaven. Once more his cinematic muse, Julianne Moore (who starred in Haynes’s astonishing 1995 drama, Safe) is wonderful as Cathy Whitaker, a 1957 Hartford, Connecticut housewife whose closeted gay husband Frank (Dennis Quaid), propels her into a taboo-shattering secret affair with Raymond Deagan (Dennis Haysbert), a black gardener.

The surface tensions quietly roar in Far From Heaven, resulting in a smashing simulacrum of not just Technicolor melodrama but also of the classic women’s pictures of yore. Sexual repression, forbidden love, collective fears, bigotry, and the vivisection of social mores are given new and unexpected élan as cinematographer Edward Lachman’s skillful lensing and Haynes’s subtle palette of deep colors sharply spotlight Moore’s delicate portrayal of demure, restless middle-class American femineity.

Cruelly honest and quite brilliant, Far From Heaven is one of the most immaculately accomplished melodramas around. Not to be missed.

15. Melancholia (2011)

There’s a certain je ne sais quoi about Lars von Trier’s hypnagogic and deeply pensive apocalyptic powerplay Melancholia that cinches it as one of the director’s very finest motion pictures. For one, it’s so rare a thing that a film capture with such startling insight and due diligence the emotional state that depression casts upon the individual, and for anyone who’s wrestled with that black dog they can easily see the naked truth in Kirsten Dunst’s chef-d’oeuvre central performance as Justine.

Von Trier, with Melancholia, playfully and profoundly upends sci-fi convention in a tense and dangerous spring-loaded narrative that pivots around newlyweds Justine and Michael (Alexander Skarsgård). These ill-fated lovers tie the proverbial knot just as the world at large learns of the presence of a rogue planet, “Melancholia”, which is believed to be on a near-collision course with Earth and will most certainly be an extinction level cataclysm.

And while that synopsis sounds like another dirge from the oft-gloomy von Trier, a fair share of gallows humor inhabits the film –– look no further than Udo Kier as the wedding planner of the apocalypse and try not to chuckle at the drollery of it all.

Led by Dunst’s luminous performance, ably backed by Charlotte Gainsbourg as her sister, Claire, both hanging on the speculations and suspicious that the End of Days might not be so dour for everyone. The film also presents a formal elegance –– perhaps best displayed by the slo-mo grand-scale eradication gracefully captured by the Phantom HD Gold cameras –– resulting in a lushly unforgettable bookend of astonishing and shocking visuals. An absolutely unforgettable showpiece.

14. Inside Llewyn Davis (2013)

The 21st century has seen brothers Joel and Ethan Coen continue to make some of the most exciting, innovative, and thrilling films of their careers, and any number of their films from this era could make this list, but we opted for their out-of-nowhere left turn into the New York folk scene of the early 1960s, and the listless eponymous folk singer, Llewyn Davis (Oscar Isaac, superb).

Bolstered by French cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel (whose superb lensing history includes 2001’s Amélie, and 2009’s Across the Universe), Jess Gonchor’s faultless production design, and the Coen’s own impeccable editing prowess, Inside Llewyn Davis is all overcast skies, doleful folk, soured relationships, escaped cats, troubled troubadours, and all with no discernable direction home.

Of course the T Bone Burnett produced soundtrack helps make the bygone Greenwich Village vibe all the more embodied, fictional or not, and rarely has the New York winter looked so chill, while simultaneously being so eccentric. Astonishingly, the Coen’s have tapped into the deep well of clever and complex comedy à la Ernst Lubitsch, with compositions as eye-poppingly gorgeous as their greatest work, of which Inside Llewyn Davis ranks amongst.

13. Under the Skin (2013)

A deeply thoughtful and profoundly shocking exploration of civilization and humanity, Jonathan Glazer spent nearly a decade on this dark hearted epic. Comparisons to Stanley Kubrick and Andrei Tarkovsky are appropriate and easily supported, as are the carefully constructed visual sensibilities and quasi-documentary leanings of Claire Denis and Lynne Ramsay. Loosely using Dutch author Michel Faber’s satirical 2000 sci-fi novel Under the Skin as the alpha of this deep, metaphysical and mercurial treatise on, well, us, Glazer has surpassed expectation.

Scarlett Johansson is outstanding, she shines in a controlled and calculating process as she moves from childlike cherub to rouge-lipped iconoclast, all while saying very little. Seducing working-class blokes at random, she lures them into her alien lair with terrifying and deeply troubling results. Her motives remain unclear in what amounts to an unaffected nightmare.

Mica Levi’s score adds heft to Glazer’s artfully arranged visual compositions, culminating in a third act extravaganza of upset and intrigue.

An elaborate subterfuge of a film, ethereal and arty all the way, it’s an unnerving, unpredictable, and sense-rattling experience that will alternately haunt and reward the patient viewer for days afterwards. Under the Skin does just what its provocative title promises, make no mistake. It’s also something of a masterpiece.

12. The Master (2012)

A polarizing but prominent director, Paul Thomas Anderson is, as Rolling Stone’s Peter Travers suggests, “…a rock star, the artist who knows no limits.” Travers goes on to say rather astutely that “ [The Master is] written, directed, acted, shot, edited and scored with a bracing vibrancy that restores your faith in film as an art form, The Master is nirvana for movie lovers. Anderson mixes sounds and images into a dark, dazzling music that is all his own.”

Anderson’s The Master presents a powerful and precise portrait of a troubled, violent, and often soused drifter named Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix), suffering from shellshock after WWII he eventually, in 1950, runs into the charismatic cult leader Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman). Mentoring Freddie, Dodd brings him into his religious movement, the Cause –– a simulacrum for Scientology, and Dodd of L. Ron Hubbard.

A compelling, challenging, maddening and invigorating film, cinematographer Mihai Mălaimare Jr. (who deservedly won many awards for his fine work here), presents a fluid and unbroken chain of high contrasting imagery. This is one haunting and lamentable honey of a picture.

11. I’m Not There (2007)

One might be tempted to apply the oft-used term “biopic” to describe Haynes’s I’m Not There, a film “inspired by the music and the many lives of Bob Dylan”, but it’s more accurately a ravishing extended in Dylanology. Featuring no less than six actors as aspects of Dylan’s multifaceted self (among them Cate Blanchett, Marcus Carl Franklin, Richard Gere, and Heath Ledger), the resulting film is an unconventional, inventive, high-flown, and absolutely beaming musical rollick that spans the five intoxicating decades of Dylan’s entertainment career.

Displaying a gobsmacking supply of contrasting visual styles, unique and varied editing techniques, and lionhearted performances from a virtuoso cast (Blanchett’s brilliant performance deserved all the acclaim and awards it mustered but also outstanding is Charlotte Gainsbourg’s heartbreaking turn as Claire Clark) make certain that I’m Not There is an absolutely singular cinematic experience.

Not once in the film’s dense and dulcet 135 minutes are the words “Bob Dylan” even uttered, and none of the cast who portray him go by such nomenclature, and yet the transience and inscrutableness of identity is given truly golden confidence and poetry. To call I’m Not There a tour de force is matter-of-fact, that it’s ambitious, challenging, surreal, and occasionally beautifully byzantine is likewise a foregone conclusion.

Haynes’s films, and I’m Not There in particular, often contend the blur of passion and pretension in the protagonist. This obsessive and persistent Dylan film displays all of Haynes’s preoccupations in one form or another, making it the ultimate and most authentic compendium of his tremendous work. It provokes laughter, tears, elation, and endless revelation.

10. Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003)

From one of the major players in New Taiwanese Cinema (next to Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang), Tsai Ming-liang details urban alienation with the deft eye of a master. Goodbye, Dragon Inn, set inside a doomed movie temple on the eve of its closure, demonstrates Tsai’s signature slow cinema approach of long fixed shots and abrupt eruptions of surreal humor –– often courtesy of the expressive and paradoxically impassive actor and muse, Lee Kang-sheng.

In this film the Fu-Ho movie palace is populated by forlorn souls, both living and dead, wandering and wondering within the faded, once embellishing interior, ravenous for connection. Outside the Fu-Ho a torrential downpour drenches the streets of Taipei, establishing and underscoring a tangible yet allusive sense of ghostly melancholy that torments and troubles the picture in what is widely and rightly regarded as Tsai’s masterpiece.

9. Children of Men (2006)

Alfonso Cuarón has directed many wonderful films so far this century that would be worthy of this list (2001’s Y Tu Mamá También or 2013’s Gravity amongst them), but his 2006 dystopian drama Children of Men is the real deal genuine article.

Sharply adapted from P.D. James’s 1992 novel, Children of Men is a bleak, brutal, technically dazzling marvel of misgiving, mental stress, and intense action. Clive Owen leads a champion cast (Clare-Hope Ashitey, Michael Caine, Chiwetel Ejiofor, and Julianne Moore are also on the scene) through the final, fragile days of dying out humanity in the year 2027. With the human race rendered infertile and all of society crumbling around them, Owen’s derisive civil servant Theo Faron must escort a pregnant refugee (Ashitey) through the chaotic and crumbling remnants of the UK.

The human drama is profound and Emmanuel Lubezki’s award-winning cinematography inundates and overwhelms the viewer constantly. Many innovative and ingeniously clever choreographed single-shot sequences catapults the film into the stratosphere, making it an exemplar of visual storytelling and easily ranks it here, high amongst the new century’s very best. Wow.