At this stage in his prolific and subversive filmmaking career, confrontational provocateur Lars von Trier’s brand is essentially one of polarization. Antichrist (2009) and Nymphomaniac (2013) are two of the Dane’s most recent examples of artful, dark, and indulgent films that managed to cut crowds right down the middle, and with von Trier’s latest detour into the abyss, The House That Jack Built makes those earlier films feel like appetizers for a banquet hosted by the Marquis de Sade.

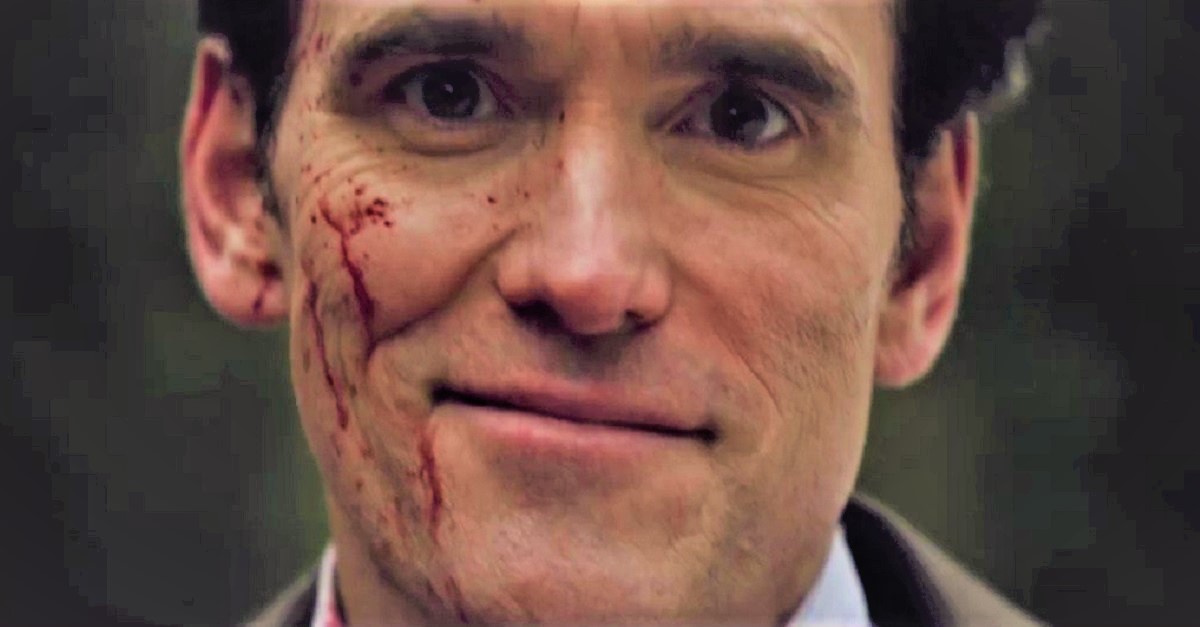

In my many years attending the Vancouver International Film Festival I’ve never seen a film provoke such inverse reactions. The majority of attendees seated around me got up and left in outrage around the time Jack (Matt Dillon, excellent) performed his macabre mastectomy on a fraught and weeping young woman named Simple (Riley Keough) –– itself a sordid leaf torn from Jack the Ripper’s libretto. Granted the audience, like the scandalous one at Cannes, were a mixed bag of nescient festival goers and genre fans.

Equal parts foolish and fearless, von Trier’s serial killer comic-thriller is also undoubtedly one of the most personal films in the director’s oeuvre, and it’s a strange, deeply unsettling rush of viscera, verisimilitude, and dark invention.

Occupying a 12 year span during the 70s and 80s in the Pacific Northwestern United States––an area traditionally thought to be a hotbed for serial killer activities––The House That Jack Built follows the career of our titular murderer, sometimes referred to as “Mr. Sophistication” and in Dillon’s cruelly capable hands, he makes for a hellborn villain to rival such contemporaries as Henry (played by Michael Rooker in 1986’s Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer), Buffalo Bill (played by Ted Levine in 1991’s The Silence of the Lambs) and Patrick Bateman (played by Christian Bale in 2000’s American Psycho).

As Jack leads the viewer down an ever-swirling quagmire of obscenity and slaughter, he shares a back and forth with an almost unworldly figure named Verge (Bruno Ganz)––a perhaps too obvious sobriquet that bluntly suggests he’s Virgil to Jack’s Dante on a tour through Hell and Purgatory.

It’s fascinating to view von Trier reworking slasher genre tropes (an isolated psychotic male killer, a pseudo-explanation of the killer’s motives, many of the victims are viewed as sexually transgressive, many of the violent assaults are intimate and all the more brutal for it, the authorities are utterly incapable of eliminating the killer, and a twist ending that’s both shocking and shrewd), as well as overturning narrative conventions. Unblinking and unflinching focus is given to psychosexual deviance, homicidal mania, and Glenn Gould’s precision as a pianist.

Von Trier rewards those who stayed for the film’s final reel with a dazzling, druggy, seriatim vision of Hell that owes much to the deeply detailed “Il Purgatorio ed il Paradiso” engravings and illustrations by Gustave Doré. This formal elegance (with props to von Trier’s semi-regular cinematographer Manuel Alberto Claro, in their fourth collaboration after Melancholia and Nymphomaniac) atones for much of the film’s earlier transgressions.

The film’s detractors aren’t unjustified in finding this to be a film of violent pornography, and the low culture status regularly dished out to movies of this sort will not escape it, but nonetheless it’s a self-consciously reflexive, self-defeating, convention-crushing, neo-slasher that will reward the right kind of viewer with its masterful mesh of allusions, pitch-dark designs and dismayed poetry.

Taste of Cinema Rating: 4.5 stars (out of 5)

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.