There is something complicated about the concept of beauty. In addition to not being able to define or direct it exactly, due to its subjective character, it seems difficult to identify something as purely beautiful, since throughout our lives we have become accustomed to cataloging everything that pleases us aesthetically as beautiful.

However, as we bring this issue into the field of art, it can become even more complex. What would be, after all, a beautiful movie? Throughout the various centuries of art history we can follow how this concept has changed and expanded. What was once considered not beautiful could be considered wonderful shortly thereafter.

Starting from the etymology of the word, we find something curious that helps us understand a little of why this happens: the Greek term for the adjective of beautiful is koine, originating from the same term that originated the word ‘hour’, hōraios. Thus, from its origins, beauty was directly associated with being in agreement with its moment, in tune with its time, or even at its best moment.

Anyway, we can think that there is also something beautiful about the complexity of this term, and think that many films may have been considered beautiful at some point in history and later forgotten, or even not having their beauty understood at the moment of realization.

The choice of the films listed below had as their main criterion, in addition to selecting films that are probably not well known even to the cinephile audience, films that have a beauty that is more than simply aesthetic or narrative; films that somehow managed to find beauty in unconventional situations and images.

10. Shower (1999, Zhang Yang)

Master Liu is an elderly man who, with the help of his younger son Er Ming, maintains a thriving traditional bathhouse in a small town in China, which has had a loyal clientele for many years. He prides himself on working hard every day and keeping his establishment running for so many years, and always skeptically positioning himself for any kind of innovation his clients propose. Master Liu, however, has a great frustration in his life, which is that his eldest son, Da Ming, did not choose to work in the bathhouse and decided to move to the large city of Shenzhen.

Er Ming has mental problems and one day decides to send a letter to Da Ming saying he misses him, with a drawing that made his brother think that Master Liu had died. Da Ming rushes back to his hometown and discovers the misunderstanding, yet decides to stay for a while. From then on, the inevitable generational conflict and an emotional reckoning with his father and his past began to take place.

“Shower” is a comedy with dramatic tones that deals with a very recurring theme in contemporary Chinese cinema, which is the dichotomy between tradition and modernity, permeated by the great and rapid economic and social transformations that the country has been going through in the last decades, and both fraternal and father-son relations are treated with great tenderness and grace. It is remarkable how the film seems to build from this approach a very mature view of reality, valuing traditions at the right point but not sounding reactionary.

9. The Amorous Ones (1968, Walter Hugo Khouri)

Walter Hugo Khouri is known in his country for (at a time when the cinematic movement that would later become known as Cinema Novo, where filmmakers like Glauber Rocha made politically and aesthetically engaged cinema, preferred to make films outside this scope, addressing more intimate and psychological themes) being sometimes compared to the Italian Michlangelo Antonionni, or even the Swedish Ingmar Bergman.

“The Amorous Ones,” made in 1968, already set in the midst of the toughest years of Brazil’s military dictatorship, may be one of Khouri’s most political films but nonetheless doing so in a very particular and different way than what Glauber Rocha, Leon Hirzman, and other Brazilian filmmakers were doing.

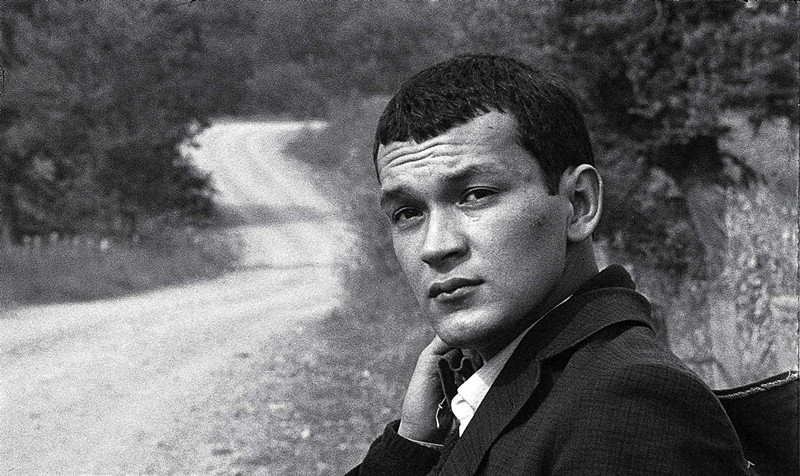

The film follows the life of Marcelo, a young college student plagued by indecision about his future, regrets about the past, and anxiety about his present. He is almost always broke and lives on hard terms with his friends. All of Marcelo’s frustrations are gradually more pessimistic about life in general, and what once seemed to be a kind of existentialism is gradually becoming increasingly strong nihilism.

Marcelo is always looking for a meaning for life, and this search will lead him to the most diverse experiences with different love affairs and relationships with other exotic characters. What is most beautiful about the film, aside from this search for the meaning of life in the blasé attitude toward the meaning of life, is this new vision that the film engenders about the existential crisis of a young university student, permeated by the context of psychedelia and tropicalism of Brazil from the 1960s, with emphasis on the participation of the band Os Mutantes, a very influential psychedelic rock group in the Brazilian music scene of the time.

8. Woodpeckers Don’t Get Headaches (1974, Dinara Asanova)

Dinara Asanova is perhaps one of the most talented and at the same time unknown filmmakers of the 1970s. Born in Kyrgyzstan, part of the Soviet Union at the time, she directed about eight films; the most well-known of them – yet somewhat obscure to the greater audience – is this coming-of-age film that delicately portrays the protagonist’s childhood dilemmas.

Mukha is a boy who dreams of becoming famous as a drummer in a rock-and-roll band. However, it annoys him that few call him by name, only reminding him that his brother Mukhin is a successful basketball player, the true pride of his family and local community. Such frustration facing the boy is also shared with his school friends, each with their own problems and dilemmas.

At one point, Mukha falls in love with Ira, a girl he knows at school, and the film’s narrative focuses on these three main aspects: the way Mukha faces the fact that he is always in the shadow of his famous brother; his attraction and attempt at conquering Ira; and his dream of becoming a great rock drummer.

Although rock is the protagonist’s dream, it is free jazz that permeates the soundtrack of the film, making in many sequences an efficient relationship with the montage and creating scenes of remarkable rhythm and musicality that helps set the tone of mess and the confusion of the youth of Mukha and his friends, and even of building the boys’ own identity.

7. Kauwboy (2012, Boudewijn Koole)

There are a huge number of films about childhood that portray it beautifully, but few films can do so by addressing a less prosperous or troubled context. This seems to be the case with “Kauwboy,” a film that accompanies the childhood of Jojo, a 10-year-old boy living with his father, a middle-aged man with alcohol problems and depressed by his wife’s departure.

Jojo’s relationship with his father is not very easy, but everything gets even more complicated when the boy finds an abandoned bird and decides to bring him home. Jojo knows that his father will never allow an animal to be present inside the house, and tries to keep it hidden until his mother’s birthday, as he still believes she will return to their lives.

“Kauwboy” is a film that deals mainly with relationships and the beauty that coexists, not always harmoniously, between the different personalities of Jojo and his father. We see all the early maturity necessary for the boy to deal with his volatile and unstable father, as well as all the love he has for his distant mother being directed to the fragile bird he decides to take care of, and his relationship with the jackdaw that somewhat resembles Ken Loach’s classic movie “Kes.”

6. Kamome Diner (2006, Naoko Ogigami)

Failure is more commonly portrayed negatively in film, and it does not seem difficult to imagine why. In “Kamome Diner,” however, Naoko Ogigami seems to reverse this logic a bit by finding beauty in the resignation and willpower of a Japanese woman who decides to open a small restaurant in Helsinki’s city center.

The film tells the story of Sachie, a young Japanese woman who travels alone to Finland, where she decides to live and try her luck by opening Kamome Diner, a small restaurant whose main attraction is its famous rice balls. The start of business is complicated, and Sachie has trouble getting regulars. His first customer is Tommi, a friendly young Finnish man who earns free coffee for being the first customer in Sachie’s short restaurant history. Shortly thereafter she meets Midori, who will help her at the restaurant, and further on Masako, a middle-aged Japanese woman who has lost her luggage, and they decide to help.

Despite all the diligence and whim of Sachi and Midori, it will not be easy to win the clientele, which will start to frustrate the expectations of the two young women, but it is precisely in this daily life of resilience and empathy that we will find the most beautiful elements in the film. At one point, a mysterious man reveals a simple technique that will help Sachie make almost perfect coffee, some old women will be conquered by the taste of the rice balls, and little by little, life will go on with its ups and downs.