5. Voyage to Cythera (1984, Theo Angelopoulos)

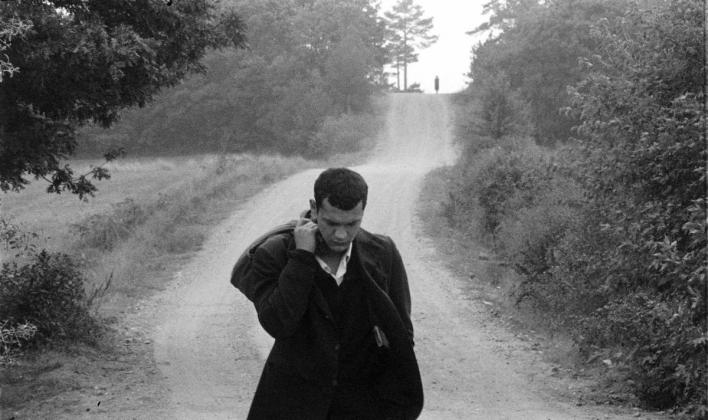

Theo Angelopoulos is one of the most recognized and acclaimed Greek filmmakers abroad, but this 1984 feature film is not among the best known of the director of “Landscape in the Mist” (1988) and “Eternity and a Day” (1998). Known for making poetic and melancholy films, here he repeats the dose in a film that can achieve a very particular kind of beauty that, although permeated with sadness, can point to a chill of hope in the course of life.

In “Voyage to Cythera,” we follow Spyros’ long and erratic wanderings in an attempt to reach the Greek island of Cythera. The man spent 32 years in exile in the Soviet Union, away from all his family and friends, and is now back in his native country. Now older, filled with frustration and doubt, Spyros prefers not to talk about his past and now tries to face a very different reality from the utopia he had dreamed of and fought with when he was younger.

“Voyage to Cythera” is a film that profoundly addresses the question of the absence of nationality, or even the lack of a homeland in which one can completely identify. Spyros spends much of the movie on an erratic journey where at one point we wonder if he really knows where he is going, or if it is the pilgrimage itself that will be his final destination. More than that, it is interesting to note how the collective imagination and the very idea of a nation are gradually being transformed from Spyros’ perspective, generating a new idea about identity and belonging.

4. Buddha Collapsed Out of Shame (2007, Hana Makhmalbaf)

This is a film that can portray with remarkable delicacy a subject of extreme difficulty and controversy. Located in Afghanistan, we accompany a five-year-old girl who dreams of studying at the city’s newly-opened school to learn to read and write, but everything around her works against it.

Obsessed with the idea of studying, she insists on the attempt, but the configuration of the society in which she is inserted always works against her goals. The little girl eventually finds a boy who decides to help her, but he is discovered and punished for it. Later, she and other girls are taken prisoner by boys who are pretending to be war soldiers.

Hana Makhmalbaf’s film emerges as a beautiful and, at the same time, harsh metaphor about the conditions of women’s lives in a totalitarian and warring society. The religious dogmas, anachronistic traditions, and day-to-day instrumental violence of a warring country relentlessly affects the lives of its characters, causing adult civilians to be overwhelmed with apathy and powerlessness, while children have only to mimic the imaginary around them, in a rehearsal form for what awaits them in the future.

The way in which Makhmalbaf’s film builds it all, using non-actors and the whole of children’s imagery, is quite potent in elaborating on a very serious critique represented in an almost unpretentious and delicate manner.

3. The Small Town (1997, Nuri Bilge Ceylan)

Nuri Bilge Ceylan is perhaps one of the filmmakers who can best deal with a recurring theme, but not always well-addressed by many films: the issue of living in small and isolated cities, as well as the psychology of the characters inserted in this environment in front of countless possibilities and opportunities that the world away from where they were born can offer them.

“The Small Town,” Ceylan’s first feature film, not only deals well with this issue, but also shows how beautiful it is to discover and choose the fate of these characters, who face the dilemma of leaving or not leaving the place where they live, whether or not to flee to the big city, whether or not to try to follow their dreams when it is not known for sure if they can come true.

The film follows the daily life of Saffet’s family, a young man somewhat tired and bored of the monotonous life he leads there. The boy thinks of leaving the small town, but the first part of the movie is focused on slowly revealing to us the lives of members of Saffet’s family and the other ordinary characters in the small town: Barber, a crazy beggar, school children, and merchants, among others.

The sense of community is very important for the film, which will often touch this point as one of the issues in Saffet’s dilemma: is it worth giving up the community in which you grew up to venture into an unknown world? But on the other hand, we will also see that community life is not exactly perfect, and that conflicts are also present.

Much of the film is devoted to a long dialogue around a bonfire, in which Saffet’s family discusses various subjects, recapturing stories from the oral tradition. There is the figure of the engineer, someone with the experience of having already left, achieved his goals and returned with a certain glory, but there are also examples of failure that frighten Saffet, which during the dialogue will lead a small ideological clash about leaving.

2. Portrait of a Young Girl at the End of the ’60s in Brussels (1994, Chantal Akerman)

In 1994, a French television channel called some well-known names from the Belgian and French cinematography scene to each make a medium-length narrative – about 50 to 60 minutes – that would be part of a series called “Tous les garçons et les filles de leur âge” (name in reference to the famous song by Françoise Hardy) and each episode should deal with the childhood/adolescence of a certain period in a certain place.

Chantal Akerman, a well-known Belgian filmmaker at the time, was one of those chosen (along with names like Claire Denis and Olivier Assayas) and if in choosing her episode title she was quite assertive and simple, it is with the young girl’s personality that she had chosen to portray that we will see a greater degree of complexity.

Michele, the protagonist, is a 15-year-old girl who spends most of her days skipping school to go to the movies. On one of these escapades she meets Paul, a 20-year-old who decides to desert the army. The two fugitives end up having a quick and evolving affair, and from there, they take to the streets of Brussels to discuss their futures, anxieties, frustrations, and insecurities.

It’s remarkable how soon the film can build such a complex personality as its protagonist, and that’s exactly where we’ll find one of the film’s greatest beauties: Michele has often shown herself to be self-confident and purposeful, but little by little, we will note the typical hesitations and insecurities of the late teens.

Paul, for his part, will present the doubts and fears encountered in early adulthood, and in one of the most beautiful scenes in the movie, when they both dance together in a dark room to the music of Leonard Cohen’s “Suzanne,” we may feel like their own destinies are intertwined with life’s difficulties and insecurities, and how the film can see beauty in this situation.

1. My God, My God, Why Hast Thou Forsaken Me? (2005, Shinji Aoyama)

This obscure feature film by Shinji Aoyama, released in 2005, featured a plot as unconventional as its title, which refers to what would have been one of Jesus’ seven phrases uttered at the time of the crucifixion, according to the Bible. In the not-too-distant future (the narrative takes place in 2015), a virus spreads around the world and puts society in danger.

The disease is named “The Lemming Syndrome” and causes those infected by it to commit suicide after moments of deep sadness. The hopelessness of finding a cure for the disease begins to despair everyone, until an unlikely solution eventually arises: music, particularly the noise genre, quite popular among some Japanese artists, emerges as a possibility of healing and hope for society.

Starring Japanese noise artist Masaya Nakahara (aka his stage names, Violent Onsen Geisha and Hair Stylistics) alongside well-known actor Tadanobu Asano (who in the movie is physically very similar to the well-known Japanese noise artist Merzbow), the film bets on long scenes and minimal dialogue to accentuate the melancholy tone of the world it tries to represent, but at the same time elaborates a very beautiful picture about the resilience needed for those facing psychological problems like depression, as well as touching on empathy and solidarity.

There is a certain tension subtly explored in the movie, which concerns the well-known number of suicides in Japan, some of the highest in the world: how do they differentiate those infected by the suicide virus from those who simply want to end their own lives?

Amid the chaos brought on by the disease, the concert scene is undoubtedly a beautiful piece of cinematic art that deserves to be seen by more people. “My God, My God”. is a film that can find beauty in a dystopian future through its argument, which seems to tell us that it is only by overdosing on the things and people we love that we can make sense of our lives and move on.