Being a great director is a little bit like being a great sportsman. It’s all about maintaining form. And just like a soccer player such as Messi or Ronaldo might have a run of five perfect years in a row, some of the very best filmmakers have strong periods where they keep knocking out hit after hit.

These great stretches of filmmaking are crucial when it comes to discussing the best directors of all time, as it shows that they can maintain a high level of quality over a sustained period of time. No director can keep making classic after classic, with even the best of them faltering now and then. Still, this list celebrates the times when it felt like they could never get it wrong.

In this article we will list the ten best five film stretches in cinema. Spanning from USA to Germany to Japan, these auteurs have proven themselves to be some of the very best in the business. Additionally, almost all of them have worked with the same crews from film to film, maintaining an artistic consistency across all aspects of production.

Whether they were courting madness, simply trying new things or constantly refining their personal craft, these five films are the best place to start with each director. Think we missed any important filmmakers on this list? Please let us know your opinions below.

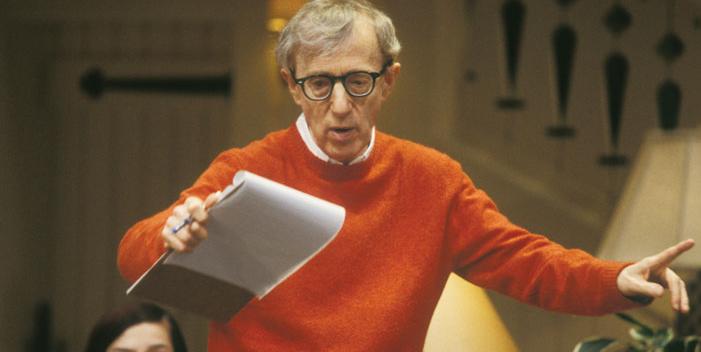

1. Woody Allen (Zelig, Broadway Danny Rose, Purple Rose of Cairo, Hannah and her Sisters, Radio Days)

After the critically mixed reaction to Stardust Memories, Woody Allen went back to the drawing board with Zelig. Predating Forrest Gump by eleven years, it cleverly inserted the central character into historical footage. The result is perhaps his most unusual movie, a study in chameleon-ism that doubles up as a fascinating portrait of the banality of evil. The film took so long to make, he wrote, directed and released the poor A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy in the meanwhile.

This proved the career comeback he needed, going on to create one of his best characters in Broadway Danny Rose, which saw him as a talent manager taking care of Mia Farrow as a gangster’s moll. Next up was Purple Rose of Cairo, which beautifully depicted an actor in a film walking out of the cinema into the real and tragic world of 1930s New Jersey. This was followed by Hannah and Her Sisters, a deeply human drama about relationships and the meaning of life, and Radio Days, a nostalgia fest with shades of Altman’s best work.

As the director is so prolific, you could argue that this was his second great five-film stretch. His earlier, funnier work, leading from Bananas to Annie Hall, is also incredibly strong. I chose the second stretch as the diversity of work is clearer and the risks bolder.

2. Federico Fellini (Nights of Cabiria, La Dolce Vita, 8 1/2, Juliet of The Spirits, Satyricon)

If Fellini only made these five films, he would still be one of the ten greatest directors of all time. This span also serves as a great way to see how neorealism gave way to personal surrealism, spanning from the tragic yet essentially simple tale of Nights of Cabiria to the scathing Ancient Roman portrait of Satyricon. He seems to gain something new, brave and vital with each film, making this one of the most satisfying movie marathons you could ever partake in.

Perhaps most startling is how Fellini managed to follow up his masterpiece, La Dolce Vita, with 8 1/2, a film that is very much its equal. Fellini was so burnt out by La Dolce Vita that he used this artistic confusion to inspire his next highly metafictional film, exploring the role between art and artist in contemporary society.

Additionally, comparing the black-and-white and relatively pure vision of Nights of Cabiria with the fantasy comedy drama Juliet and the Spirits shows two different approaches to womanhood that nonetheless complement each other brilliantly. He would never achieve quite the same level of artistry again.

3. Alfred Hitchcock (Vertigo, North by Northwest, Psycho, The Birds, Marnie)

The late 50s and early 60s represent an extraordinary period of innovation and creativity for Alfred Hitchcock, basically inventing four different genres in the process. Vertigo changed the film noir forever, a haunting film that functioned like a puzzle.

North By Northwest basically predicted the James Bond films with its combination of action and adventure — including massive spectacle — all tied up in a spy conspiracy bow. Finally, Psycho changed the horror movie forever, using misdirection and mood to create a deeply unsettling work – inspiring everyone from Brian DePalma to John Carpenter.

The Birds may not have been so influential, but its essential conceit, and terrifying use of mood, predated Jaws in its use of scary creatures haunting locals in a rain-stricken town. Marnie, which paid respect to German expressionism, is perhaps not as important, yet it still remains a deeply effective psychological thriller. It’s harder to name a more influential stretch in the history of popular cinema.

4. Steven Spielberg (Raiders of the Lost Ark, E.T. the Extra Terrestrial, Indiana Jones and The Temple Of Doom, The Colour Purple, Empire of the Sun)

Coming after the deeply personal yet deeply flawed 1941, Steven Spielberg needed a hit, and boy did he get one! George Lucas approached him saying he wanted to develop a new version of James Bond, but with whips and hats instead of guns and vodka martinis.

With the help of screenwriter Lawrence Kasdan, Indiana Jones was born. Raiders of the Lost Ark was an amazing hit, a nostalgia-filled homage to old-time serials that kept the thrills coming right until the final scene.

He followed the first Indiana Jones instalment with E.T. the Extra Terrestrial, one of the most iconic family films ever made. Another Indiana Jones film followed, The Temple of Doom, which doubled down on the horror to provide a particularly dark kids film.

Most directors would be content working in this simple wheelhouse, yet his follow-up The Colour Purple — one of the few great films of the 80s with an all-black cast — is a devastating experience, while Empire of the Sun is a fantastic adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s autobiographical novel which expertly portrayed the loss of innocence.

5. Martin Scorsese (The Last Temptation of Christ, Goodfellas, Cape Fear, The Age of Innocence, Casino)

Martin Scorsese tried forever to get The Last Temptation of Christ made. In the meantime, he made After Hours, which was a fantastic satire of yuppie entitlement, while The Colour of Money didn’t have quite the same energy as his best films.

Once he was finally successful with his Jesus Christ film, it seemed to rejuvenate the director to make some of his finest work. Goodfellas really speaks for itself as a brilliant portrayal of the allure of mob life, which along with the editing work of Thelma Schoonmaker, created a highly exciting way to develop narrative.

While Cape Fear was seen at the time as a genre exercise — a mere remake of the 50s noir — it deserves reconsideration as one of Scorsese’s most essential films due to the terrifying performance by Robert DeNiro.

On the other hand, The Age of Innocence is the ultimate lesson in how to adapt a period drama and make it feel vital, featuring possibly Daniel Day-Lewis’ best performance. Casino went back to the same stomping ground as Goodfellas, but was invigorated by its incredible camerawork and editing, as well as Joe Pesci’s electric performance.