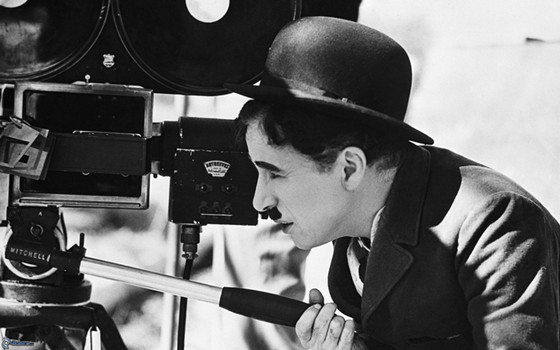

6. Charlie Chaplin (The Gold Rush, The Circus, City Lights, Modern Times, The Great Dictator)

Charlie Chaplin’s iconic stretch from The Gold Rush to The Great Dictator, spanning fifteen years from the sound era to the silent era, is a great example of why it’s better to take things slowly. Every film is near perfect, a combination of comedy and pathos unequalled in action-oriented cinema.

The Gold Rush is a fine portrayal of the craziness that descended upon the American West at the end of the 19th century. From there The Circus is a riotous display of madcap antics that never loses heart, while City Lights is the quintessential romantic comedy of the 1930s.

Even as the rest of the industry moved to sound, Charlie Chaplin refused to change, releasing Modern Times in 1935. Here topic and form complimented each other very well, its exploration of an increasingly modernised society well reflected by his classic interpretation of silent film tropes. Then with his first sound film The Great Dictator, he took aim at none other than Adolf Hitler himself, creating one of the most rousing anti-fascist films ever made.

7. Krzysztof Kieślowski (Dekalog, The Double Life of Veronica, Three Colours Blue, White and Red)

Perhaps we are cheating a little here considering that Kieślowski’s Dekalog is a TV series. Nonetheless, you could take any film in that ten episode anthology and declare it as great.

Based upon the ten biblical commandments, it shows the Polish director’s unique use of empathy and narrative to create difficult moral quandaries. A Short Film About Love and A Short Film About Killing, feature length adaptations of two of the stories, make fine features in themselves, and are definitely worth watching.

He followed Dekalog with The Double Life Of Veronica, which starred the stunning Irène Jacob as two identical women who don’t know each other yet whose lives are inextricably linked. After that was one of his most ambitious projects yet, the Three Colours Trilogy, each colour representing a part of the French Flag. The eventual result is a stunning statement on shared European values and the human condition.

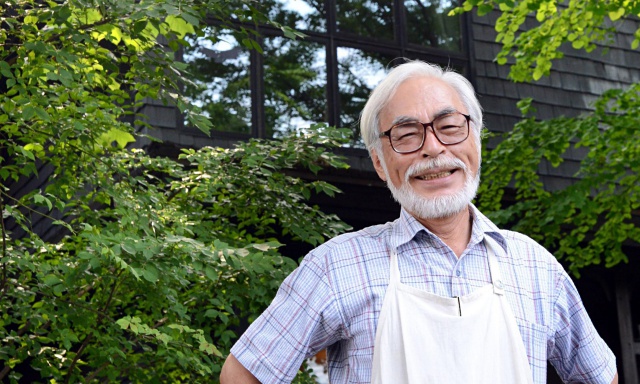

8. Hayao Miyazaki (Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Castle in The Sky, My Neighbor Totoro, Kiki’s Delivery Service, Porco Rosso)

Miyazaki’s early work represents the pinnacle of what animated film can do. Nausicaä of The Valley of the Wind used it to address environmental issues while Castle in The Sky combined wonder and awe with action adventure tropes. Then came his finest two films, and two of the finest depictions of youth, My Neighbor Totoro and Kiki’s Delivery Service.

The former is a strong contender for the best animated film ever made while the second turned witch stereotypes on their head to create a stirring tale of self-belief. For Porco Rosso, he continued with one of his key obsessions, the love of flight, to tell the story of a pig airplane pilot who never stops fighting for what he believes in. These films put Miyazaki on the map as the one of the best ever animators, second only to Walt Disney himself in his epic yet humanist vision.

9. Denis Villeneuve (Prisoners, Enemy, Sicario, Arrival, Blade Runner 2049)

Since pivoting from films in his native French language to the world of Hollywood, Villeneuve has created one of the best bodies of work in the current decade. Prisoners, aided by gorgeous cinematography by Roger Deakins, was a dark and mysterious crime thriller that was as much about the characters pursuing the case than the case being pursued. The dirty follow-up Enemy saw Jake Gyllenhaal play against himself in a strange doppelgänger thriller, while Sicario plunged into the intense darkness of the war on drugs.

Since then he has injected new life into big budget sci-fi with Arrival and Blade Runner 2049. With an upcoming remake of Dune coming up, easily his most difficult task considering how poor David Lynch’s attempt was, it’s hard to say whether Villeneuve can maintain his form. I wouldn’t bet against him!

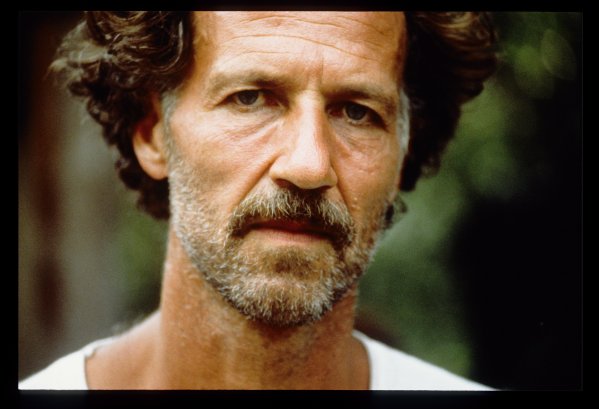

10. Werner Herzog (Aguirre: The Wrath of God, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, Heart of Glass, Stroszek, Nosferatu The Vampyre)

There has been no director like Werner Herzog. His work stands apart from the rest of cinema, eternally interested in questions of the human condition. Aguirre: The Wrath of God made a star out of Klaus Kinski in depicting the hubris of man’s desire to dominate others, while The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser was a character study simply unlike anything else. For Heart of Glass, he took a brave risk by actually hypnotising the inhabitants of the village he was filming, while Stroszek gleefully inverted the concept of the American dream.

The final film in this stretch confirmed him as one of German’s finest filmmakers with a remake of F.W Murnau’s Nosferatu, an icy take on vampire tropes that is renowned for its glacial beauty and mesmerising, strange performances. Taken together, these five films saw Herzog constantly constantly push himself with each film — perhaps preparing him for his greatest masterpiece (not on this list), the sensational Fitzcarraldo.