5. The Young and The Damned (1950) – A soul flies like a bird

Quite before his orgasmic creation of surrealist cinema and during his long-lasting period of life in exile, Luis Buñuel made a stunning piece of post-war neorealism that showcases a small yet unforgettable grain of surrealism.

This is “Los Olvidados.” Shot in an original environment of Mexico City, this early gem in Buñuel’s career shares the thematic completeness of the European film movements of the era, as it glows on an evasive reflection of the auteur’s forthcoming surreal illustrations.

Born in the impoverished neighborhoods of Mexico that precariously survived the destructions of World War II, Pedro is just another kid steeped in the dirt of a land abandoned in criminality and corruption. After El Jaibo, a young and completely immoral criminal, returns in the neighborhood so as to take revenge for his denouncing, Pedro is doomed to co-opt his master’s fate, rooted in a soil of lost chances.

In this swamp of ethical sediments, there is a sunbeam of hope. There’s a Buñuel’s escapist cerebral channel. All of the story’s corrupted adolescents used to be like Pedro and perhaps Pedro will soon be like them. But before his heart is filled with mud, his dreamy thoughts are afraid of violence. His still innocent soul flies like a bird, asking for his mother’s tender embrace. This moment of clarity and pureness washes out the film’s gloomy context, surviving in memory forever.

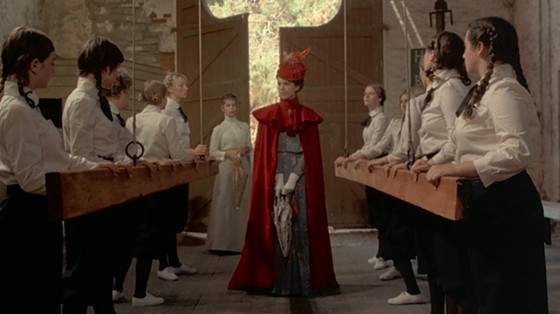

4. Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) – Why does she wear a red dress?

Portrayed on a visually meticulous canvas of symbolic imagery, the mind-controlling masterpiece “Picnic at Hanging Rock” by Australian director Peter Weir comprises an artistic, even poetic exculpation of the sexual awakening.

If one attempts to follow the story’s happenings, as they lead toward the signs of an unsolved mystery, then the film’s thematic core is hardly touched. But if you let yourself free in this poem’s allegoric maelstrom, then the tangle unfolds all at once.

Superficially, the plot describes the missing of four girls after a school trip at a volcanic rock. We see the adolescents, accompanied by their sexless teacher, moving forward to the hill’s top, as if controlled by the primal force that expelled it from the earth’s deepest level. Fascinated and unstoppable, the young women dispose of their clothes until they’re lost forever. After days, one of them is back.

Irma experienced a sexual awakening and then returns to her casual environment‒ a place of conservatory superstitions and repressing incitements. She stands in her red dress of femininity surrounded by numerous white-dressed girls that doesn’t comprehend her situation. They are angry and aggressive while she’s standing still in her glowing appearance. This is a stunning interpretation of the first coming-of-age processes.

3. I Am Cuba (1964) – The funeral

Famous about its extremely demanding and effective camerawork, “Soy Cuba” by Soviet director Mikhail Kalatozov is an on the prerevolutionary Cuba, depicted on an almost unbearable beauty that creates a sad echo in its grim content. From Havana’s nightclubs to the countryside’s labor, the film’s exposes all of Cuba’s bleeding wounds before Fidel Castro’s prevalence.

A young woman who lives in a hut surrounded by mud and barefoot children works as a prostitute in the bars of Havana, where frequent rich foreigners. An old peasant is forced to abandon his only fortune ‒comprised by bluffs of sugarcanes‒ when the landholder sells his property.

The house of a poor family with many children is bombarded. A leftist university student is cold-bloodedly assassinated by the corrupted government. “Soy Cuba,” a narrator insists to say each of the times.

Even though “Soy Cuba” includes numerous breathtaking scenes, in relation to camera movement and frame, there’s one that seems like a miracle: After the student’s assassination, a procession accompanies his body in the city’s streets. The camera moves vertically and after passing through few parallel balconies, it observes the parade from up above. This scene doesn’t engage the perspective of those who grieve but hovers over them and grieves for their pain as well.

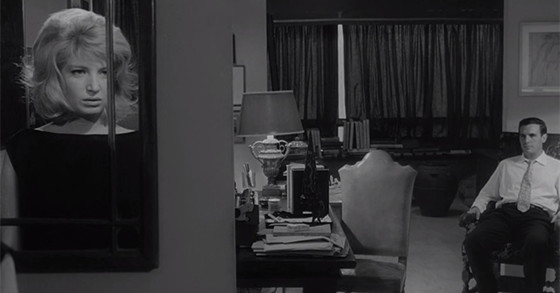

2. L’eclisse (1962) – Vanity will break the silence

Arguably, Michelangelo Antonioni’s cinema comprises a demanding task. His subtle interpretations of a multilayered yet ordinary object that is planted in a gentle humane backdrop can be decoded after close observations. Various existential concerns are obvious in several Antonioni’s works. Nevertheless, our beingness never felt as vain as in his 1962 enigma of “L’eclisse.”

Monica Vitti as Vittoria is found in the epicenter of the film. She has just decided to break free form a long-lasting relationship that seemed to vegetate, in order to continue seeking a scope in her life. In her materialistically regulated environment, everyone longs for a daily satisfaction which could render a meaning in the totality of days that we call “life, “always in a much different way than Vittoria.

Although she eventually came together on one level with another man, their moments appear as feathers in the wind. In the streets where they used to meet, other people shared moments. Other women followed Vittoria’s steps. Would any of those moments and people last forever? One’s occurrence in this world is slightly longer that an eclipse, if you dare to consider eternity.

“L’eclisse” is a deeply existential cinematic piece by Antonioni, adequately synthesized in terms of cinematography. Even since the first shot sequence, when Vittoria is ready to leave her boyfriend once and for all, their insecure positioning, their inner hesitation, even their bottomless existential voids effortlessly emerge. Carefully choreographed in a frame of space, time and ideas, this sequence deliver’s the picture’s substance without needing the layering of words.

1. 8½ (1963) – Back to childhood’s games

Reflecting one of his own periods of inspirational crisis on Marcello Mastroianni’s troubled eyes, Federico Fellini’s “8½” is something more than a personal work. During the course of one of his film’s shootings, Guido Alsemli is a director who seeks a satisfying destination for his film. Constantly carrying the loads of his present’s terrors and under the shadow of childhood’s memory, he essentially strives to find the deeper meaning of filmmaking.

Guido Alsemli, gracefully embodied by Mastroianni, represents Fellini’s alter ego. Experiencing a mature age that has offered a full conscience and has costed a formed sense of unconcern, Guido constantly searches an inner self through his relationships and professional activity, while he can’t avoid a strong ingredient of the free child he once used to be and still lives somewhere inside his heart.

Throughout the stunning amalgamation of memories and nightmares that it is ““8½,” we are a lot of times allowed to visit Guido’s past through his spontaneous retrospections. The most striking throwback, perhaps, takes place during a party: a clown reads two words in the mind of Guido.

These words practically mean nothing, but for Guido, they incite a mental push to his childhood’s games. Such a direct reaction to a personal code is a transcendental act that concerns every human being. Fellini, as one of the greatest artists of moving image in history, made it real.