6. Some Came Running (1959)

Vincente Minnelli’s star-studded adaption of James Jones’s mammoth novel of the same is arguably the best melodrama of classic Hollywood (that wasn’t directed by Douglas Sirk, of course).

The film stars Frank Sinatra who plays an alcoholic writer who has just returned from the war. He comes back to his small hometown in the Midwest, where his brother (Arthur Kennedy) owns an extremely successful jewelry store.

And that’s essentially the set-up for the movie. Though it doesn’t sound exciting, Minnelli somehow manages to tell this story in such an epic, dramatic scale that it ends up feeling more like an actual epic than any Douglas Sirk film.

It’s fairly long at around 2 hr and 20 min, but the characters are so compelling and the plot is so enthralling that it feels perfectly concise. Minelli will most likely always be known for his timeless musicals like An American in Paris and Gigi, but he truly excelled in the genre of melodrama.

7. Underworld U.S.A. (1961)

With what is arguably the best post 1930s/pre Godfather gangster film, Sam Fuller peaked as a director. Underworld U.S.A. tells the story of a man, Griff, in his mid-30s, recently released from prison, who sets out to avenge his father’s death. In the first half of the film, Griff almost plays the part of a private detective, desperately tracking down the four remaining gangsters who murdered his father some 20 years before.

Once he tracks them, though, he doesn’t simply kill them. Instead, he gradually infiltrates their crime syndicate, working his way up through the ranks until he is working closely with his father’s killers.

The rest of the film from that point on is an awe-inspiring series of violence, somewhat reminiscent of the “Layla” montage at the end of Scorsese’s Goodfellas. Fuller’s Underworld USA serves as the perfect bridge between the classic pre-code gangster films and the New-Hollywood revival of the genre led by Coppola and Scorsese.

Yes, Underworld USA, was director Samuel Fuller’s peak, but that doesn’t mean his later films weren’t of equal quality. In particular, Shock Corridor is by far one of the greatest portrayals of mental illness in film history. The Naked Kiss is also a great post-noir, though not nearly as good as the other two.

8. La Collectionneuse (1967)

The third entry and first feature length film in Eric Rohmer’s Six Moral Tales serves as a perfect example of its author’s great talent at writing dialogue. It’s easy for a film centered around conversation to bore most viewers, but that’s never the case with Rohmer. Part of what makes his dialogue so fascinating and enjoyable is his rich characters and the relationships they have with each other.

La Collectionneuse follows an art dealer and an artist, forced to share a vacation home in the Riviera with an eccentric young woman. There aren’t any major plot twists (not that there is much of a plot to begin with) but instead it is a study on the way relationships transform and is a classic use of the “love triangle” story.

The beautiful warmth in the coloration of the film makes it all the more enjoyable, along with the breathtaking scenery of the French Riviera. Though not quite his first feature film, Collectionneuse is without a doubt Rohmer’s breakthrough, the film that paved the way for the rest of his consistent career.

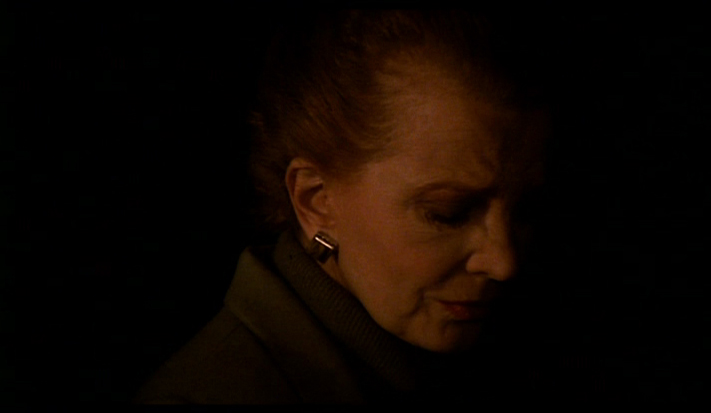

9. Another Woman (1988)

Some of Woody Allen’s best films are his colder, Bergman-influenced dramas like Interiors (1978), September (1987), and Match Point (2005). But among the best of this category is also the most underseen: Another Woman.

The film stars Gena Rowlands (known mainly for her films with her late husband John Cassavetes) as a writer who slowly becomes addicting to eavesdropping on her psychiatrist neighbor’s appointments with a patient, played by Mia Farrow.

Another Woman is Allen at his psychological best. This is a very minor film, and that seems intentional. It lacks the darkness of Interiors, instead replacing it with an analytical look into the mind of an aging, divorced woman.

Film critic Roger Ebert stated, “This is a film almost entirely composed of moments that should be private.” Essentially what Ebert meant was that this doesn’t quite feel like a film that was written and directed by a person, but rather that it’s almost as though you are spying on someone through a security camera.

10. Paper Moon (1973)

Paper Moon is perhaps the modern movie with the most authentic Golden Age of Hollywood influence. If seen without any context, one might assume it was made in the mid-1940s and directed by someone like John Ford or Frank Capra. This resemblance isn’t strictly visual, though; the story feels like one that could have only been told during that era.

At the time the film was made, director Peter Bogdanovich was surrounded by people who couldn’t have been more different. He may as well been a member of Classic Hollywood: he was best friends with Orson Welles (they even lived together for a while), had his first script rewritten by his friend Sam Fuller, directed the fantastic documentary Directed by John Ford, and spent much of his time interviewing heroes like Fritz Lang, Howard Hawks, and Allan Dwan.

Whereas his contemporaries sought to defy the Hollywood system and the conventions of American film, Bogdanovich’s goal seemed to be to perfect those conventions, to pick up where the old masters had left off. And somehow, in the early 70s, he actually succeeded.

Paper Moon is a lighthearted, playful portrait of a man’s (Ryan O’Neal) relationship with a little girl whom he suspects is actually his daughter (Tatum O’Neal). Again, the film’s beautiful cinematography is heavily reminiscent of a mid-period Ford film like Stagecoach or Young Mr. Lincoln, but Bogdanovich absolutely maintains his own style, despite his strong influences.