The following films are of amazing narrative and aesthetic quality. Most of them have been Oscar-nominated, or at the very least, swept the National Awards of the respective countries of their production.

For one reason or another, they have been unjustly semi-forgotten or relegated to a kind of second-tier of cinematic achievement by many critics and film historians.

1. Bye-Bye (1995, Karim Dridi)

The 25-year-old Ismael and 14-year-old Mouloud move from Paris to their benevolent uncle’s crowded house, in a working-class neighborhood of Marseille. Ismael and Mouloud don’t just leave Paris behind, but they also try to escape their past, as a tiny bit of subtle dialogue alludes to a tragedy that occurred while in they lived in France’s capital.

The parents – immigrants from Tunisia, Northern Africa – return for good to the old country, while they instruct Ismael to send over Mouloud after some time in Marseille. While Ismael scores a job on the docks of Marseille and befriends Jacky, the owner’s son, major complications throw both brothers’ lives into turmoil. Ismael falls for his new buddy’s girlfriend, precipitating Jacky’s older brother’s blatant racism into violence; while Mouloud, unwilling to return to Tunisia, ends up being recruited by Renard, a paranoid crackpot and sociopathic heroin dealer.

The film captures an extremely atmospheric Marseille, while also offering an entertaining exploration of relevant contemporary social issues in France (racism toward the North African community, the difficulty of social integration and coping with accidental tragedy) all presented in a fresh and intoxicating manner. However, the storytelling is somewhat fragile.

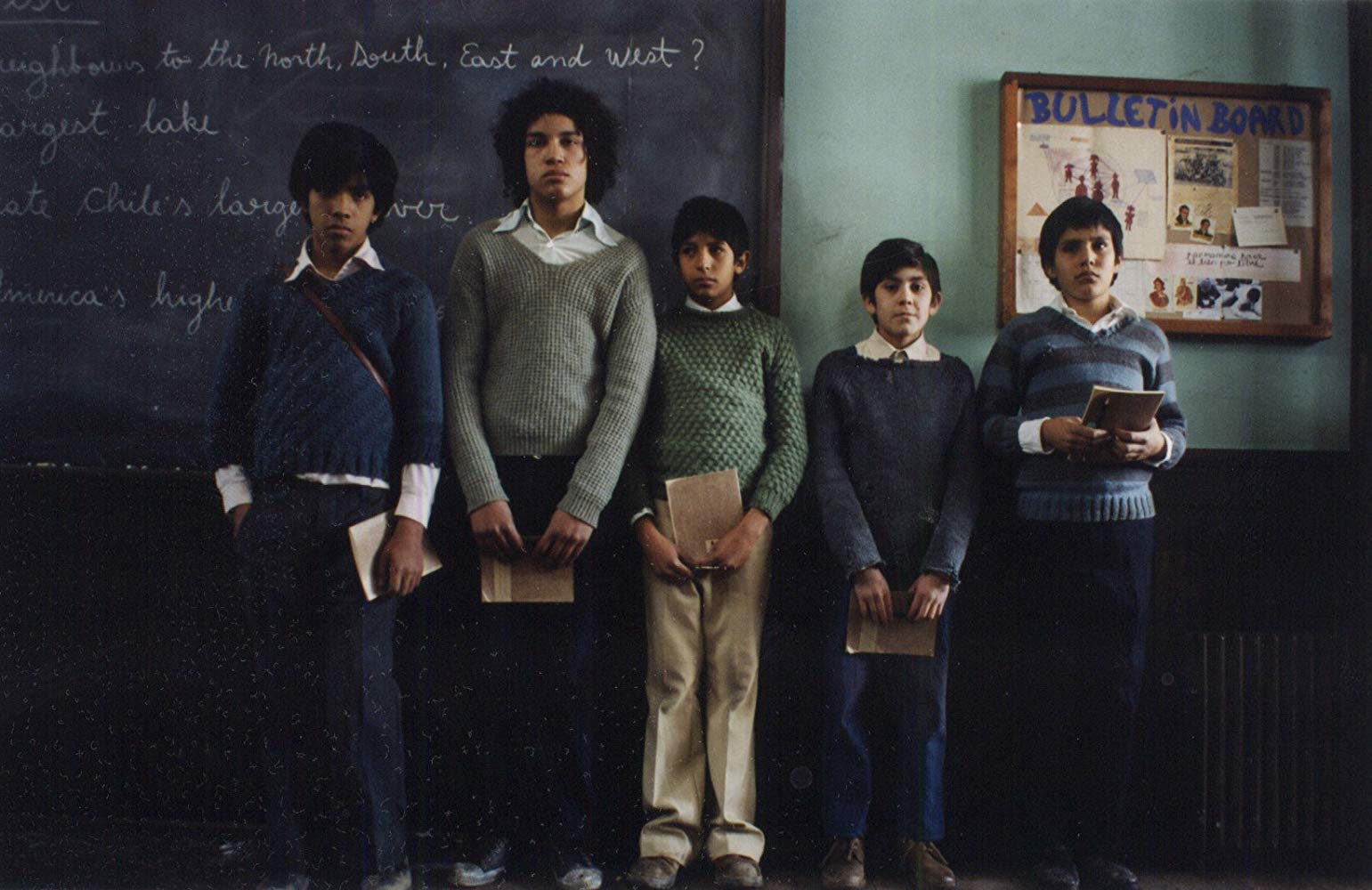

2. Machuca (2004, Andres Wood)

An elite all-boys school in Santiago, Chile during a time of great political volatility, the early 1970s. The 11-year-old Gonzalo, belonging to an upper-class Santiago family, forges a genuine friendship with Pedro, a courageous and determined shantytown kid, who was brought to the elite school by the integrative vision and no-nonsense character of Father McEnroe, the school Master.

Gonzalo is an intelligent kid on the verge of adolescence with an affectionate but snobbish mother, who despises the poor, and a cool and permissive Dad (who is mostly absent.) Gonzalo doesn’t buy into his classmates’ hostility for the recently integrated peers, who come from extremely poor families. Also, Gonzalo instinctively can’t stand his sister’s violent zombie crypto-fascist boyfriend.

Gonzalo’s innocence and benevolent nature don’t disintegrate despite being subject to bullying on the school patio, and even after accompanying his mother to an embarrassing rendezvous with an older rich guy who tries to both keep Gonzalo entertained and buy his complicity by offering him Lone Ranger comics. The friendship with the new school peer, Pedro, somehow transcends all the rigid caste beliefs of the Chilean upper class, as the new classmate goes to play at Gonzalo’s house and is finally accepted as a friend.

The director Andres Wood allows the historical facts to speak for themselves, yet manages to keep the friendship at the forefront of the story and the rising political temperatures in the background. The cinematography and the period details are extremely realistic, while the weather, mostly overcast and somber, succeeds in suggesting a bleak “all is falling apart” mood.

The brutality unleashed by Pinochet and the junta completely destroys the slums where Pedro and his family live, under the pretext of “reinstalling order” and “hunting down communists.”All of the kids from the slums are thrown out of the school by the soldiers, while Father John declares that the place has been desecrated and is arrested. Shortly after, Gonzalo is reciprocating Pedro visits by playing at Pedro’s parents’ house, during another intervention of the army.

Not only does Gonzalo witness firsthand the army’s arbitrary dragging out of people from their homes, but he barely saves himself with his wits and a piece of brilliant improvisation, asking a soldier to look at his face and at his fancy sport shoes, in order to signify his belonging to a very different socio-economic class.

The soldier, who is no doubt familiar with Chilean society’s extreme “classism,” has a moment of utter perplexity and then releases Gonzalo. The official propaganda claims the next day, with a mix of typical right-wing ludicrous euphemisms and mindless junta triumphalism, “that order is restored and everything is perfectly normal.”

The children’s performances are extremely convincing and almost flawless. The film holds extremely well, while the portrayals are nuanced and well balanced. Gonzalo’s father, a member of the upper class, is a laid-back, hedonistic guy and a sincere believer in “equality of opportunities” while Pedro’s father is a cynical alcoholic.

The children’s limited comprehension of the darkest hour in Chilean history is compensated by virulent emotions and a lack of adherence to adult dominant values (ambition, hypocrisy, and opportunism). Also remarkable is the fact that the children never fall into Hollywood black-and-white heroism.

3. Four Days in September (1997, Bruno Baretto)

The true story of a group of idealistic middle-class students in Sao Paulo that, in July 1969, kidnap the American ambassador in order to circumnavigate the severe censorship of the press and call attention worldwide to the brutality of the Brazilian military dictatorship.

Three college students discuss their views on the dictatorship in Brazil and possible involvement with MR 8, an underground organization fighting the military dictatorship.

Fernando is a talented speechwriter but certainly no ”guerilla warfare material” as he’s hopelessly uncomfortable and inept with guns, while his chubby buddy Cesar is a naive seminar student completely unaware that he will be soon in something well over the top of his head.

After an anonymous bank expropriation that no one finds out about, Fernando, now rebaptized “Paolo” inside the communist guerilla group, has a “brilliant” idea – to kidnap the U.S. ambassador in order to force the military junta into ”collaboration” and pass all the revolutionaries’ messages on national TV, in order to avoid the killing of the American diplomat.

A smart, nuanced and well-written political thriller, Bruno Barreto’s “Four Days in September” was a well deserved Brazilian entry for the Oscars and certainly carries the “gravitas” of a real story.

4. Lovers of the Arctic Circle (1998, Julio Medem)

A lush, mesmerizing, and ravishingly beautifully shot love story. A complex poetic vision encompassing Basque director’s Julio Medem’s vision of destiny.

Anna and Otto meet at the age of eight as they attend the same school. Later, as teenagers, they become siblings as their single parents fall in love and move together. Finally, they are reunited in their mid-20s in a hut in Finland, precisely the mythical and geographic place crossed by the imaginary line of the Arctic Circle.

Medem nonchalantly plays with the unfolding of the story, as time flashes forward and then we go back in time to experience the same scene through the eyes of a different character. Both Anna and Otto have comprehensive voice-over narration that border on excessive at times. Even so, these film passages are rendered intoxicating by the very fluid mise en scene and Medem’s particular brand of delirious melancholy.

5. Exiled (2006, Johnnie To)

Two mob squads arrive in Macau before the island will be returned by the Portuguese to China, in the very late 1990s. Wo is a former hitman who retired from the mob and live a quiet existence with his wife and infant child (at least, before the arrival of mob former buddies). While one squad comes to claim Wo’s head for having retired without the blessing of mob’s boss Fay, there is another squad, composed of old buddies, that come to warn and protect Wo.

After an initial fight, all of the participants clean up the place and sit down to a feast as Wo apparently agrees to the last hit of his career, in order to generate enough income for his family.

The plot doesn’t have any great depth or any mind-boggling twists. However, what catapulted Johnnie To’s film to the Venice and Toronto Film Festivals, as well as the hearts of scores of fans worldwide, is the wild, extravagant, and extremely polished mise en scene. Style over substance? Yes, unfortunately, up to a certain degree!

While the characterization might have had more depth and the plot might have been elevated by a bit of either black humor or absurd detail, the cinematic experience is still absolutely phenomenal. The wind blows through open windows during the Antonioni-esque shootout while wide-angle highly stylized spaces give the arena, where extremely choreographed confrontations occur, a spectacular feeling.

A really amazing tour de force in the crime genre with superbly crafted camera work, highly suggestive framing, and a consistent hard-boiled mood that suits the tough and violent lives of the hitmen. Johnie To’s film is in tune with the subtle and complex codes of the Hong Kong crime genre. Yet “Exiled” is not a cold and virtuoso masterpiece in terms of mise en scene, but also really engages the audience emotionally. Another fascinating aspect is that the characters’ emotional bonds and childhood friendship still somehow at times transcends loyalty to the mob.