6. Matador (1986, Pedro Almodovar)

The first collaboration between Pedro Almodovar and Antonio Banderas, two years before “Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown,” Almodovar takes a darker turn from his early pulpy John Waters and black comedy melodrama-inspired films, and creates a film that would define many films in his career.

From the opening of this film, you enter the world of Almodovar with the bright colors, mix of genres to be considered unclassifiable, erotic sex scenes, and murder. The narrative keeps you on the edge as you truly never know what is around the corner, but who cares when these images and emotions flow over you.

Since it was a departure from his early works and before his return to a new height of zany comedy, it wasn’t one of Almodovar’s favorite films as he talked openly about it. However, with a stellar cast playing it so straightlaced no matter the level of sensuality or sexuality, Almodovar clearly shows he’s a director of many talents in this great film right before his commercial breakout.

7. Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench (2008, Damien Chazelle)

This was originally the thesis film for Damien Chazelle while he was at Harvard, and he decided to finish the film for $60,000. The film received its fair share of recognition at festivals, but it’s the true beginning for this director and it shows in this great musical indie.

The influences and style are clear in this film; Jacques Demy and Hollywood Golden Age of Musicals is clear on screen, but it’s Chazelle’s intense and personal storytelling that resonates. First off, it’s a love story in the jazz world that would define his massive breakout hit “La La Land” and even “Whiplash.” For example, at a dorm-like jazz party, the camera whip pans between the band and several people dancing, a motif that he used in his two latter films as well.

Chazelle knew what he was doing, but was on a micro -budget with non-professional actors and performers. Despite more elaborate productions, the film stands out right before the digital revolution and narrows down this filmmaker’s choice of style, content, and emotion, all here in this film, no matter how small or recognizable.

8. Blind Chance (1981, Krzysztof Kieślowski)

Upon entering the 1980s, Krzysztof Kieślowski would reach new stature as he moved from his documentary roots to being a true poetic, cinematic director. The first film of the decade for him was a film told in three different outcomes regarding whether our protagonist Witek catches the train to Warsaw.

The film is told in three diverse stories: the first where Witek catches the train and becomes a loyal communist, the second where misses the train and becomes an anti-communist protestor, and the third where he misses it but resumes his original path of being a doctor and falling back in love.

It wasn’t until 1988 with his masterpiece “Dekalog” that he received worldwide attention for his poetic realism films. However, with this film, Kieślowski makes each part exciting because they different in overall mood and atmosphere despite being rooted in what was still communist Poland in the 1980s.

With each story where he runs after the train, it becomes a thrill ride that Kieślowski truly makes it entertaining as a chase film. But it isn’t until the third story, where the first two were polar opposites, where we see where it might be heading, and appreciate the true artistic prowess of this film and filmmaker.

Kieślowski’s work would continue to garner attention and acclaim, but beginning in the 1980s with this film, we realized he was great.

9. Blackmail (1929, Alfred Hitchcock)

The first official sound film for himself (and for Britain) after nearly a dozen silent pictures, Hitchcock blasted onto the scene, showing that he was a director with visual and sound elegance that the world would come to know and love.

Hitchcock would gather more critical and commercial attention in the 1930s with “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” “The 39 Steps” and “The Lady Vanishes” before his entrance to Hollywood royalty would begin in the 1940s and reach a climax in the 1950s. But with his first talkie film, he was able to express more with sound.

The film is fairly straightforward as a young woman is blackmailed into being a witness for a murder, which is familiar territory for old Hitch. But it’s the use of sound and pure visuals that we see he would use for his entire career. Take the scene of climbing down a rope in a museum, or pan to a knife being held behind someone’s back – all these motifs would explode later on. Hitchcock was doing it in 1929.

It was well received upon release, but failed to continue esteem as Hitchcock would get bigger and better. However, if one looks at this film, the suspense method, visual storytelling, and the use of sound is all there to make this a great film, way before Hitchcock became world famous.

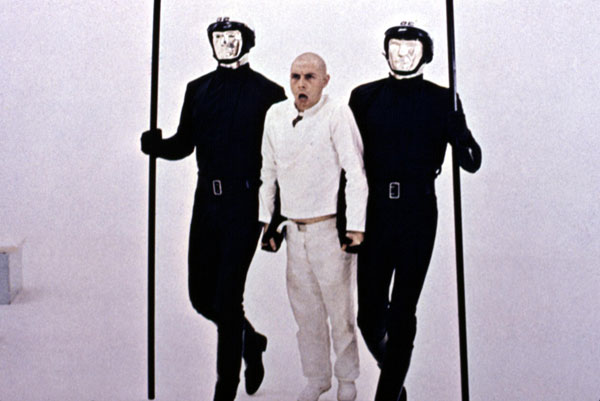

10. THX-1138 (1971, George Lucas)

Probably the most experimental and art house film George Lucas ever made, the film stars Robert Duvall and Maggie McOmie as rebels against society in a dystopian future. Expanding from his student film, “Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1138 4EB” from 1967, Lucas went all out with what he wanted to do.

With Lalo Schifrin as the DP and Walter Munch and Francis Ford Coppola on the production team, Lucas made one hell of a debut for its time. With off-kilter framing and sound design to constantly keep you on the edge, it’s a hard film to ignore, even if you don’t fully comprehend all the elements. But Duvall’s character of “THX 1138” doesn’t either, so we follow along with his journey.

Though two years before “American Graffiti” and six before “Star Wars,” Lucas showed he was an extremely meticulous and obsessed film director. It’s only been after the galaxy far, far away that audiences truly started to appreciate this film. And one definitely should, at it stands for a critique on the times in 1971, the beginning of the movie brats of the Hollywood New Wave, and an intense arthouse film that leaves no cinematic elements to waste and allows the audience to make their own interpretation.