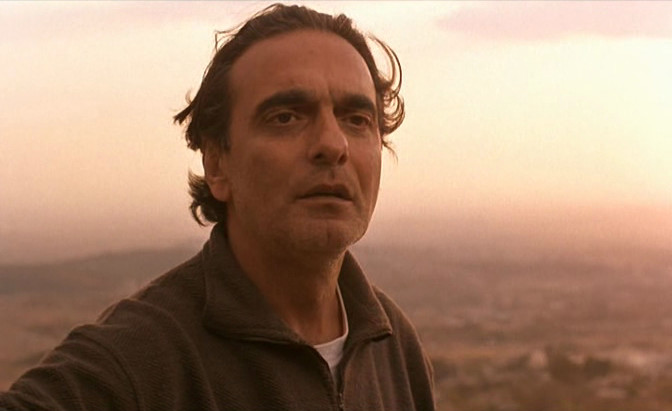

5. Taste of Cherry (1997, Abbas Kiarostami)

In “Taste of Cherry,” we follow the saga of Mr. Badhi, a 50-year-old Iranian who tirelessly roams the streets of an Iranian city in search of something rather unusual: a person who will help him commit suicide by pledging to bury his body after he commits the ultimate act. Mr. Badhi will address a number of characters and the three who agree to get in his car are quite different from each other. One is a young man in the military, another is a middle-aged religious man, and there is also an old taxidermist.

It is not by chance the age and social variety of each of these passengers: each of them emerges as a representation of an aspect of life that the embittered Mr. Badhi will be leaving behind in ending his life. Inside the car, each of them will present countless arguments for Mr. Badhi to give up his plan; he remains convinced, promptly countering each of these arguments and exposing his negative view of existence, as if the film had a constant dialogue between hope and despair.

There is an interesting mix of misanthropy and loneliness in Mr Badhi’s character, something that is evident in his lines, and helps the viewer feel sorry for the protagonist, who seems both firm and sure of his decision, but not less desolate and distressed inside.

4. Werckmeister Harmonies (2000, Béla Tarr)

Bela Tarr is a filmmaker who has always tried to distance himself from the various comparisons that were made of his works to those of another great Eastern European filmmaker, Andrey Tarkovsky.

Of course, there are many differences and specificities in each one’s work, but it seems hard not to see in “Werckmeister Harmonies” a series of elements that show a strong influence of the work of the Russian filmmaker, especially in relation to camera work and the dilation of the film time. What is striking about the film is that Tarr is able, like no one else, to articulate such elements to reflect on the meaning of life in the midst of a world permeated with violence and cruelty.

The plot of the film is relatively simple: in a small Eastern European city, constantly surrounded by fog and plagued by intense cold, the arrival of a kind of circus catches everyone’s attention. This circus has as its main attraction a huge whale, which is loaded into a truck, and the animal causes many people from other places to start appearing.

This event causes the whole routine of the city to change: strange and unfamiliar people start to arrive, and others try to take advantage of the situation. Soon an escalation of violence and revolt begins to unfold, revealing the darker side of the inhabitants of that small town.

3. Guns of the Trees (1961, Jonas Mekas)

“Guns of the Trees” is a film that shows a slightly different side to the best-known Lithuanian-born American filmmaker Jonas Mekas, both in cinematic style and in the tone of his plot. Although his most recognizable works always carry with him a melancholy feeling, “Guns of the Trees” stands out for giving a much more pessimistic view of human existence, especially the vision of the young idealist artists of the 1960s who, like Mekas himself, seemed to foresee a dark future for themselves in the face of the failure of their wills for a social, political, and cultural revolution.

The film follows four young characters who from the beginning try to understand the reason behind a friend’s suicide. Perplexed by the sudden and tragic event, we see how the state of affairs of that historical moment presented an unfavorable horizon for those young people who dreamed of a different society from the one in which they lived.

It’s interesting how the narrator at the beginning of the movie directly throws the question: “Why would a person commit suicide these days?” and throughout the narrative, the film itself responded by returning another question: how can anyone not commit suicide these days?

2. An Elephant Sitting Still (2018, Hu Bo)

“An Elephant Sitting Still” is one of those films that brings with it a great difficulty of evaluation, related to the context of its realization. It is almost impossible not to watch the movie already knowing the tragic story of its young director, Hu Bo, which makes the experience even more intense and even more meaningful.

However, it is hard not to recognize that “An Elephant Sitting Still” is one of the most distressing films of recent years, and it achieves this through an impressive articulation between its script, which portrays the bitterness of the difficult lives of the Chinese characters, and their language, which relentlessly accentuates the film’s morbid and nihilistic mood.

The script of the film uses a multiplot model in which we follow the lives of four main characters for a whole day in the same city. Their lives are linked not only by their stories, but also by the sadness in which they are immersed: each one lives in a more complicated context than the other, having problems with their family, at school or work and also in their love life. In addition, the presence of an elephant sitting around all the time in a city nearby seems to fascinate each of the protagonists.

The stories are told through long moving sequential shots, and during the nearly four hours we see the sad unfolding they end up taking. Each of the main characters will experience a climax of violence, but it is as if the film treated it with marked indifference: even after these heavy climaxes, the characters’ moods remained impassive, as if none of it, however violent and astonishing as it may be, will make any difference in “this disgusting world,” as one of the protagonists often says.

1. The Fifth Seal (1976, Zoltán Fábri)

At a bar in Budapest, just before the end of World War II, five characters are gathered: aside from the bar owner, there is a watchmaker, a photographer, a carpenter, and a book seller. The five friends drink and talk about trivial matters, until one of them raises a complicated moral issue in which one essentially has to choose between being the oppressed or the oppressor. After rambling on for a few minutes, the five characters return to their homes, but the issue will remain with them and relentlessly affect their immediate destinies.

Filled with references to the horrors of war, authoritarianism, and selfishness, “The Fifth Seal” contains a brilliant script that can take your breath away without following virtually any of the script’s famous rules. A seemingly simple question thrown in the first scene results in an impressive narrative unfolding, in which we witness the different choices of each of the protagonists.

Like “Guns of the Trees,” “The Fifth Seal” also throws a question and seems to answer it throughout the narrative: no matter which side you are on, whether as the oppressed or as the oppressive, human destiny will be the scene of suffering and despair.