5. The Adventures of Baron Munchausen

As established, the cinema of Wes Anderson is a cinema of escapism. It’s a cinema that thrusts its audience into worlds detached from reality to tell stories inherently rooted in reality. But can this elusive sense of fantasy be exaggerated to the point of sheer lunacy? Enter the cinema of Terry Gilliam.

Though the two filmmakers have entirely different approaches to the craft of cinema, with one focusing more on unique characters while the other uses characters as mere plot devices in service of monumentally ambitious narratives, there do exist some fundamental similarities between both auteurs. The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, one of Gilliam’s lesser known works, is perhaps the film that best blurs the lines between the distinctive crafts of the two masters.

Similar to the narratives of both The Fall and Big Fish, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen explores the questionable tales and antics as recounted by the titular Baron Munchausen, an aged adventurer. Where Gilliam’s vision differs from Burton’s and Singh’s, and concurs with Anderson’s, is in the underlying element that drives his unique vision- his insanity.

Gilliam’s insanity is what breathes life to the film, it removes distinction between that which is objectively real and that which isn’t, creating a truly surreal cinematic experience that not only remains an absolute joy to watch unfold, but one that remains surprisingly consistent from a tonal standpoint.

Films like Twelve Monkeys and Brazil may be too ostentatious in scope to serve as companion pieces to the cinema of Wes Anderson, but the fairy-tale like atmosphere built by The Adventures of Baron Munchausen certainly does break through the impregnable wall that is Gilliam’s madness, making the overall experience of the film one that captures the spirit of an Anderson picture, albeit just a few degrees on the insane side.

4. Paddington

Paddington is the epitome of children’s cinema as an art form. Aside from bringing to screen a beloved childhood character in a wholesome manner that cinematically embodies all the little intricacies of his being, Paddington is a film that embraces the often shunned yet classic formula of storytelling with little deviation. Yet instead of feeling remotely clichéd or dull, the formulaic nature of Paddington’s narrative exists in perfect harmony to the whimsical endeavors of everyone’s favorite marmalade-loving mammal.

Though the messages perpetuated by the film aren’t particularly groundbreaking or thought-provoking, Paddington’s brilliance shines not in the script, but in the presentation of it. The impression of childlike wonder and blissful playfulness leaves a prominent mark in almost every setpiece of the film’s colorful rendition of contemporary London, featuring an outlandish array of vibrant aesthetics that simply couldn’t have been a more perfect complement to the inherent nature of the film.

Paddington is a film that never remotely ever pretends to be anything it isn’t. The film remains fundamentally, a film for kids, by kids. And who would’ve ever thought that a bonafide kids’ movie would find its way past the ranks of its other forgettable genre contemporaries?

3. Mon Oncle

To experience a film made by the genius that is Jacques Tati, is to watch through the eyes of the child you once were, a cartoon on a lazy Sunday afternoon. Because regardless of your age, the timeless cinema of Tati is bound to resonate in a manner similar to Anderson’s quirkiness, albeit channeled into the understated brilliance of physical comedy.

Tati’s Academy Award-winning Mon Oncle is perhaps the best possible example of Tati’s brilliance. On the surface, Mon Oncle is a film existing without a plot. There are characters, there are minor conflicts, but none of these elements truly constitute a narrative. As a matter of fact, the entirety of Mon Oncle’s plot can be summarized in a single sentence – A bumbling uncle who’s loved by his nephew.

Though a bonafide example of comedy may seem drastically different from Anderson’s more restrained and heartfelt style of humor, there do exist similarities in the crafts of both masters. Tati’s quirky, exaggerated portrayal of his characters mirrors that of Anderson’s and the same can be said with regards to both filmmakers’ command of space and color.

While the cinema of Anderson oftentimes concerns itself with the intimate struggles of a family dynamic, Mon Oncle takes a far more distant perspective towards the matter, examining the antics-ridden circumstances as opposed to the individuals affected by said circumstances. Which, oddly enough, transforms this marvelous French comedy into an experience that runs parallel to Wes Anderson’s films.

One that examines similar subject matter, features similar stylistic trademarks, yet achieves something entirely new and refreshing.

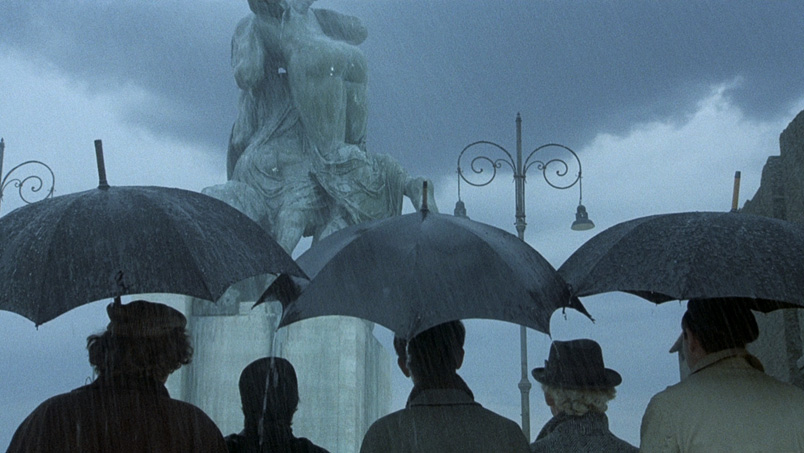

2. Amarcord

The name Federico Fellini is one that’s held with much reverence by many a film historian. Fellini is man regarded as a cinematic giant comparable with likes of Tarkovsky and Bergman. He’s an artist who, with every film, create a revolutionary piece of art that transcend all notions of criticism and pushing the art form further to what we know it to be today. One can call a Fellini film many things, but to compare it with the cinema of a contemporary filmmaker such as Wes Anderson would most certainly be unheard of. Except perhaps, when discussing Fellini’s cinematic love letter to his childhood, Amarcord.

In the same vein as Tati’s Mon Oncle, there is no concrete plot in Amarcord. What there is in place of a cohesive narrative is instead, a collection of memories stitched together by the idea of experience. Visually, Amarcord is as stunning as any of Fellini’s other works, exhibiting pure poetry in visual storytelling. Fellini uses this command of the camera to explore intimately, the cinematic landscape of 1930s rural Italy.

Though Amarcord certainly differs in tone from the cinema of Wes Anderson, there do exist numerous similarities in theme shared by both schools of cinema. The strong overarching element of nostalgia, the idea that youth, in all its chaos and mistakes, is but a fleeting moment that should be cherished is a universally profound message. One that’s paraded not only by Amarcord, but by close to the entirety of Anderson’s oeuvre.

1. Amelie

The term “style over substance” is oftentimes used as a label to condemn the cinema of Wes Anderson. Though it does ring true that Anderson’s craft is, at its core, a product of self-indulgence, is this label really to be regarded as a criticism? Or perhaps should one simply deem it as just an observation?

Diverting our attention to the cinema of Jean-Pierre Jeunet, the answer to this question becomes abundantly clear. Jeunet’s magnum opus, Amelie, is essentially the most Wes Anderson-esque a film can ever get without being actually made by Wes Anderson. There is virtually no distinction between style and substance, and Jeunet certainly makes no effort in making an attempt at that distinction.

Amelie is the quintessential definition of cinema as a form of escapism. It explores the life of the titular Amelie, a woman whose life is shaped by tragedy, death and loneliness. But it isn’t a character study. The film doesn’t depress over her circumstances like how cinema depresses over its plethora of melancholic protagonists, the titular Amelie instead embodies optimism in the face of none, seeking to spread joy and love as she herself finds joy and love.

The film is the embodiment of “style over substance” in the best way possible. It presents a world not quite of the designs of a filmmaker, but one viewed through the impressionistic eyes of its protagonist. A world that ignores all possible conflicts that can be ignored. A world that embraces the beauty of living by placing value over every little idiosyncrasy of daily life.

A world that delivers a powerful message of hopeless idealism very much in the same vein as Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom – To enjoy life while it lasts.