5. Funny Games (1997)

A well-to-do family visiting their lakeside cottage are unknowingly balanced on a precipice of disaster in Michael Haneke’s vicious home invasion film, Funny Games. And if you think about the broad strokes and the home-under-siege angle, Funny Games’ DNA runs throughout Us, at least initially.

Matriarch Anna (Susanne Lothar) has barely settled into her vacay with husband Georg (Ulrich Mühe), and young son, Schorschi (Stefan Clapczynski) when there’s an unexpected knock at the door. Two young men (Frank Goering and Arno Frisch), clean-cut and refined in appearance, with pleasant manners and inflection, claim to be friends of their neighbors and wish to borrow an egg. Trusting Anna allows the young men to enter her home where they quickly commence terrorizing and brutalizing the family.

This early film from Haneke — which he would later remake in English in 2008, shot-for-shot with a mainstream cast including Tim Roth and Naomi Watts — is borne from his more confrontational and provocative period. Senselessly deprived violence in polemical attire is paired with a feeling of hostility towards the viewer.

The sadistic tormentors frequently speak to the camera, addressing and implicating the audience in their violent behavior — which includes torture and murder, amounting to not-so-funny games for the victims. It’s an interesting tack, and one that generates troubling discourse, alternating almost unwatchable acts of savagery with jolts of jet-black comedy and dwindling hope.

4. Enemy (2013)

Enemy is Denis Villeneuve’s inscrutable adaptation of José Saramago’s 2002 novel “The Double”. It’s a chilling, indulgent, yet always audacious affair with an affection for dual identities, making it thematically not too distant from Peele’s Us.

Jake Gyllenhaal, in an understated yet riveting dual performance, is Adam, a history professor in a passionless relationship with Mary (Mélanie Laurent) who soon discovers, after renting a DVD, that an actor in a small role appears to be his doppelgänger. After a little legwork, Adam finds the actor’s talent agency, intercepts some mail and learns his name, Anthony Clair.

As the puzzle-like film unravels, the viewer is treated, amongst other existential horror high-jinx, to troubling imagery of spiders, gossamer (a web-like appearance of a cracked windshield is especially chilling), stifled femininity, a tough, washed-out looking Toronto landscape, and increasing dreamlike delusions building to an arresting conclusion and a final shot that is totally terrifying.

Enemy is a resonating work that not only does the Saramago source material a great deal of justice (which is no small feat), but presents itself as seductive cinema, sensational at times, and quick, guaranteed to pervade the viewer while offering up nightmare fuel and dark fantasy. While it may not wrap up all of its mysteries in the satisfying manner that Us does, it does dare the viewer to entertain their own dark ideas about identity and delusion.

3. Persona (1966)

Persona, rightly earmarked as one of Ingmar Bergman’s greatest films, plays passionately with the idea of the double. Here, Bergman has two actors, Liv Ullmann (in her dazzling debut) and Bibi Andersson, gradually becoming more and more similar to one another over the course of the film, their identities attaching and blurring into one another in a seemingly vampiric vein (pun intended).

Ullman is Elisabet Vogler, an overworked and exhausted actress in the charge of Nurse Alma (Andersson), who are spending time together in a secluded coastal summer cottage. It’s a beach setting distantly related to Peele’s Us.

Slowly a symbiotic relationship manifests amongst the two women. Bergman has admitted he wrote these roles specifically for them, noting their physical resemblance and chemistry. As Alma and Elisabet grow closer it becomes progressively less clear whether the two women have joined as one person.

Noted filmmaker and writer Susan Sontag has famously described Bergman’s film as a “desperate duel of identities,” suggesting that the discord between Elisabet and Alma is the classical “duel between two mythical parts of a single self” which adds much meaning and magnitude to an already influential and outright exhilarating picture.

Persona is pure cinema, a challenge to observe and give order to, to be sure, but one where the rewards are untold and absolute.

2. Mulholland Drive (2001)

For all its dark detours, and there are many, David Lynch manages to break chains of anguish and upset with odd ecstatic glee, capturing so often a world of ravaged sensitivity with Mulholland Drive. That and the use of doubles makes it a strange but oddly accommodating bedfellow to Peele’s Us.

Notably with this film Lynch handed Naomi Watts her first major role — which she knocks out of the park — one she embraces with an operatic élan of emotional extremes, not unlike Lupita Nyong’o’s stunning turn in Us.

A neo-noir mystery which, at times feels like a subversive Nancy Drew-style yarn, the wholesome Betty Elms (Watts) newly arrives in L.A., plans to breakout into acting, despite her almost comical naiveté. Betty soon meets Rita (Laura Harring), with whom she becomes fast friends and roomies, oh, and there’s Diane (Watts), a waitress, who looks just like Betty, amongst others in a Lynchian chorus of late-night and sun-soaked chimera-like characters.

An often upsetting film, anxieties and fears accumulate in staccato sequences rendered in punishing tableaux, begging the question: is what we’re seeing Betty/Diane’s death dream? Perhaps a better question is who’s-dreaming-who?

Mulholland Drive offers up sublimated desires, dual identities and Hollywood satire in a package that may well be Lynch’s finest work, or his most irksome, depending who you ask. Regardless of this, the dreamlike wanderings, intense imagery, comic sidesteps, and eerie instances certainly add up to an rememberable puzzle with alternate realities, danger, provocation, and strange shadows. It’s something of a pièce de résistance, whether the viewer wants it to be or not.

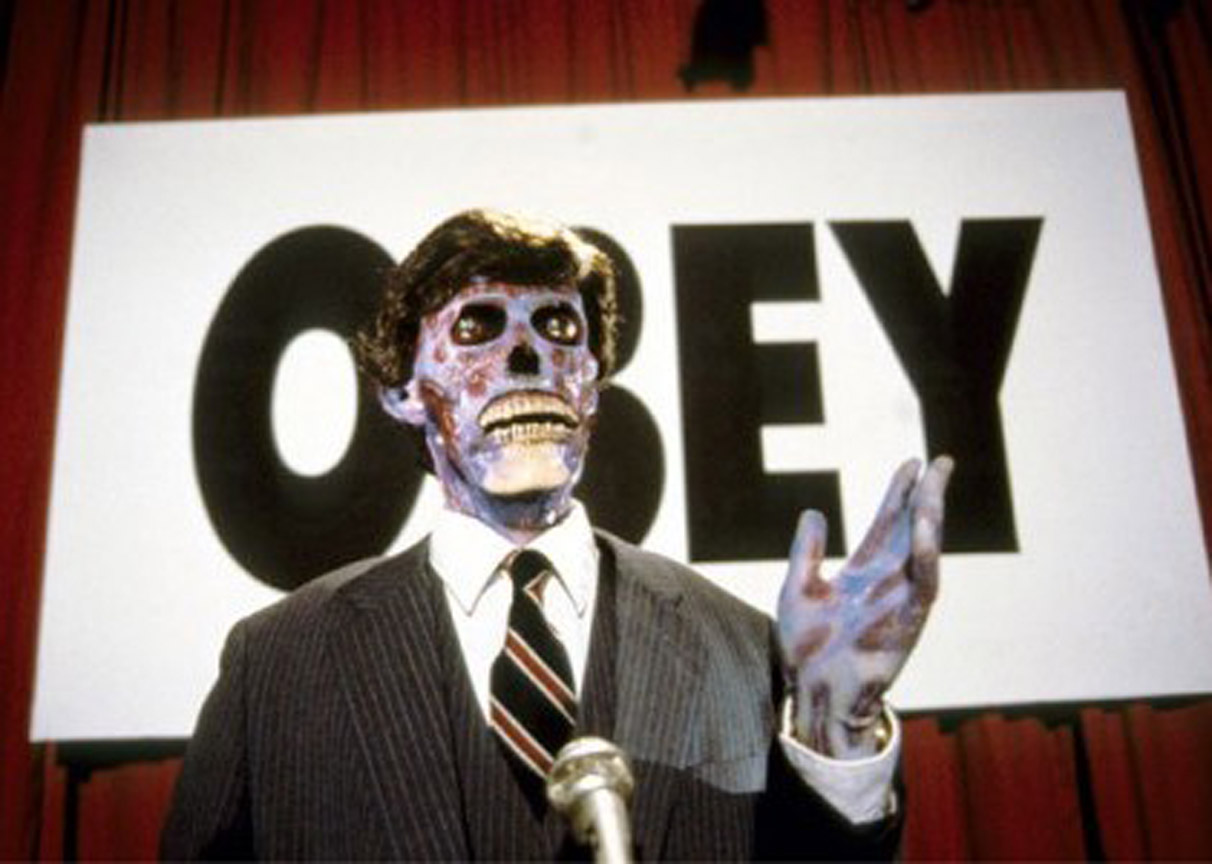

1. They Live (1988)

Perhaps at just a cursory glance very little seems to connect Peele’s Us to John Carpenter’s 1988 cult classic They Live, but as both films challenge the viewer to look closer and dig a little deeper, a throughline does tether the two in a number of significant ways. Again, without making too big a spoiler, let’s just say that both films unearth a larger conspiracy that goes much deeper than originally suspected and similarly both films strive to and succeed in making a social and political statement in the dress of a genre film.

In Martin Scorsese’s summation, “They Live is one of the best films of a fine American director,” and who are we to disagree with so knowledgeable a cineaste? And as Peele’s CV continues to grow, surely Us will be looked back upon as high water mark as well.

Like a frenzied crash course in semiotics and media manipulation, They Live is a politically subversive B-movie combining horror and sci-fi with hair-raising results. Adapting Ray Nelson’s short story “Eight O’Clock in the Morning”, about mass alien hypnosis duping humanity via TV commercials, radio, and print media, Carpenter also steeps the proceedings in satire and casts WWF wrestler “Rowdy” Roddy Piper as John Nada, our two-fisted hero.

Nada is sympathetic and relatable as a blue-collar drifter trying to get by when he stumbles upon a pair of sunglasses that breaks the alien signal allowing their hidden messages to be visible –– dollars bills suddenly read “THIS IS YOUR GOD”–– along with their hidden-in-plain-sight swarms, secretly integrated amongst us. “You know, you look like your head fell in the cheese dip back in 1957,” quips Nada to an alien, giving up his element of surprise before he even knows the stakes.

Critical of the Reagan era from which it came, They Live chronicles the early stages of humanity’s uprising against alien forces, not unlike the Tethered’s uprising in Us, for a lifetime of mistreatment and torture.

Sure, They Live requires a little forgiveness from the audience as its plot holes are gaping, but the film’s a shit ton of fun if you surrender to it, and Piper’s back-alley brawl with Keith David is a highlight, and certainly one of the longest and most mirthful fisticuffs in movie history, too.

A can’t miss cult classic that becomes more relevant with each passing year.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.