5. Chungking Express (1994)

One thing is definite: Wong Kar-Wai has got his own, distinctive cinematic character. From the use of light to the use of music, and from his characters’ icon to the predominant loneliness of his thematic landscapes, you always know that you watch a Kar-Wai’s bewildering motion picture. No other filmmaker has ever delivered the same ideas in his prompt, quite artistic and sweeping manner. However, there’s no such thing as parthenogenesis in art, and a thin surface of the French New Wave seems to happen in Kar-Wai’s world.

His 1994 “Chungking Express” showcases a freewheeling use of both camera and script. Its contextual movement describes mental states, instead of following linearly evolving events of time and reality. The great Chinese director serves a deferential verity to the pure ideas of an archetypical uncorrupted spirit, instead of the serving the requisitions of a type of immediate narration.

The start-line of the ablative narrative structure in cinema is firmly located in the French New Wave’s visual foundation, as is the unspoken exasperation that captures every corner of a silent room. In its colorful filters and stunning reflections, “Chungking Express” has a lot more in common with “Breathless,” with “Jules and Jim,” or with “Pierrot le Fou,” than you sense after a first watch.

4. Frances Ha (2012)

The recent, much-acclaimed and discussed “Frances Ha” by young American director Noah Baumbach gloriously achieves an insertion of an ordinary American girl of our present in the both dark and shiny portrait of the French New Wave. Frances lives in New York, crawling after her middlebrow issues. Her black-and-white microcosm, though, is found in a frozen drop of France’s 60s.

In a European style of filmmaking, and perhaps in a Jim Jarmusch’s way of telling an every-day story, Baumbach doesn’t rely too much on the plot’s complexity to expose his observations, as following the life of Frances. She’s a twenty-something New Yorker who happens to have ambitious dreams, despite she satisfies every possible mistake while watching the lives of her friends evolving and adopting stereotypical textures.

The topics developed in “Frances Ha” have few in common with the wide topical background of the French New Wave. Frances has not the mysterious glamour of Brigitte Bardot or Anna Karina. She’s much more conventional than them. But the way she stroll in the city, the way she inhabits rooms full of books and tapes, the way she occupies white beds, and even the way she deals with romance reminds of Godard’s Parisian adventures.

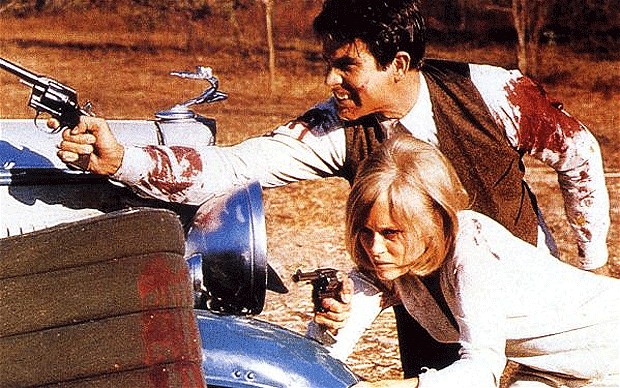

3. Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

Emerging in the very same era of the French New Wave’s occurrence, “Bonnie and Clyde” has established its own throne somewhere in between the timelessly iconic films. The story’s miserable and self-destructive criminal duo has lost none of its power in every viewer’s memory as yet. Nevertheless, their vain chase of dreams in a labyrinth of twisted morals had already happened in France’s cinema.

Warren Beatty could have been America’s Jean-Paul Belmondo, and you can’t deny it: they both glared on a similar portrait of male beauty. Faye Dunaway embodies that woman who means to accompany, get satisfaction, offer love, and still unbalance her tragic mate until a final devastation of his sentimental dysfunctions. Well, you can’t deny it either: she used to have the beauty and style of a European actress of the 60s.

Arthur Penn’s 1967 masterpiece “Bonnie and Clyde”, despite its obvious influence from the French New Wave, sustains its own visual beauty, substantial fullness, dramatic honesty and unique artistic character. Even in our days, it remains one of the best pieces of the American crime cinema, exposing an incomparably deep study of criminal behaviors and emotional complexes.

2. Eden and After (1970)

Alain Robbe-Grillet was an artist directly associated with the French New Wave. His most famous work is the script of Alain Resnais’s divisive and debated 1961 reverie of “Last Year at Marienbad.” In an even more unsettling and unbound trip in the labyrinthine castle of subconscious, he drew the free directions of his 1970 grotesque cinematic masterpiece “L’éden et après.”

It’s quite known that Jean-Luc Godard didn’t use to work on a specific and complete script. Sometimes, he used to give small pieces of paper with notes to his actors and let them improvise on them. Watching films as “Pierrot le fou” or as “2 ou 3 choses que je sais d’elle” perhaps you can sense that fact. In this fashion, in “Eden and After” Robbe-Grillet synthesizes a collage of spiritual images, a collage of ideas that resurface from the deepest layers of sentience, concerning various topics, as sexual terror and socio-political dysfunction.

Apart from its “Nouvelle Vague-ish” exposition, the film fluidly moves on a Godard’s color pallet: spots of mere red and blue float on a vast, steady canvas of white. This is the typical and distinctive color synthesis of “Pierrot le fou,” “Le mépris” and other colored works by the French legendary filmmaker. Adopting his visual style, Robbe-Grillet creates a substantial cinematic nightmare which occupies a sphere of unfailing visual beauty.

1. The Dreamers (2003)

Bernardo Bertolucci’s controversial negotiation of moral and political revolution of “The Dreamers” is in a way dedicated to the French New Wave, as it is dedicated to the essential ideas and innovating efforts of the entire movement all the same. Set at France’s fateful year 1968, the film follows young cinephiles who seek the real and hard core of art, effectually capturing the era’s atmosphere in a nostalgic environment of pure and honest beauty.

The story’s two French siblings and their American friend aren’t tragic heroes of a real-life drama. They are the heroes of the films they adore. The three of them experience a period of sexual and idealistic awakening. In both their world and mind, sexual freedom, art and rebellion are three threads indissolubly interwoven with each other. A new liberated land which is reflected on the films of the French New Wave and on a restless picture of a revolt holds the beat of their hearts.

They imitate the iconic scene of Jun-Luc Godard’s “Bande à part”, where Anna Karina and her two friends run through Louvre museum, and they break their time record. They abolish every sexual limit. They join a riot. Their acts and opinions are sometimes shocking, even nowadays. But isn’t rebellion shocking in every level when it really takes place?

“The Dreamers” is a complex masterpiece that still remains underrated. In order to appreciate its value, its truthfulness and its determinant innovation, one needs to know the French New Wave, the incidents of May ’68 in Paris, and the free spirit of Bertolucci. This film is in a way dedicated to us that love all of those values, as well.