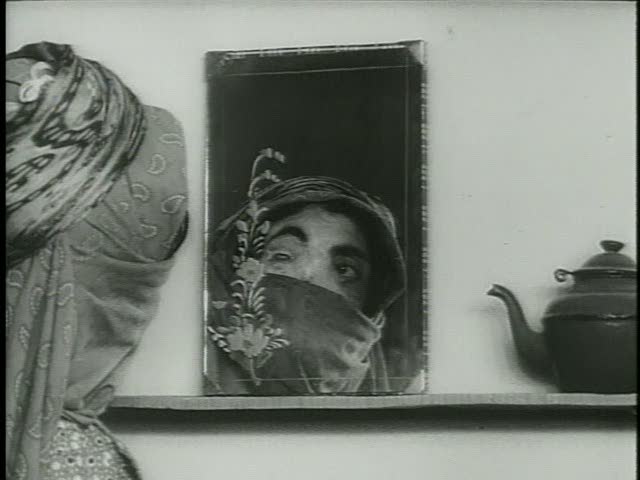

4. The House is Black – Forough Farrokhzad (1963)

Iran, Iranian New Wave

Though Iranian Cinema is perhaps best known for the work of Abbas Kiarostami, The Makhmalbafs, Jafar Panahi, and other significant figures of Iranian Cinema’s Second and Third Waves, all of it can be traced back to Forough Farrokhzad’s landmark documentary “The House is Black.”

Commissioned by Iran’s Society for Assisting Lepers, Farrokhzad spends twenty minutes introducing us to the gracious neglected population of the Bababaghi Hospice leper colony, or, as she calls it “The Land of Infinite Darkness.”

Footage of people attending class, touching the trees and buildings, and being cared for by doctors are narrated by passaged from the Old Testament, the Koran, statistics about leprosy, and Farrokhzad’s own aching empathetic poetry: “Oh overrunning river driven by the reigning force of love. Flow to us, flow to us.” Farrokhzad stages an implicit critique of normative society’s cruel tendencies towards the disadvantaged.

Early in the film, a young boy gives his thanks for being given “ears to enjoy the beautiful songs.” Later, a group of people sit around playing a board game with rocks and shells, laughing and sharing with each other non-verbally. The lyrical rather than logistical narration serves a great purpose, passages call out to religious figures for divine salvation when it is clear that the government is the only thing that can bring justice to these people.

Despite, or perhaps due to, its political undertones, is as much a celebration of those living in Bababaghi as it is a condemnation. It is a shame that Farrokhzad died at 32, because this film and her poetry in it offer us the purest method of relating to others: seeing them experience joy.

Available on Youtube.

5. Ganga Zumba – Carlos Diegues (made in ’63, released in ’72)

Brazil, Cinema Novo

Filmmaker Glauber Rocha, in his 1965 Cinema Novo manifesto The Aesthetics of Hunger, wrote “wherever there is a filmmaker prepared to film the truth… there is to be found the living spirit of Cinema Novo.” Following the bankruptcy of Hollywood lookalike film company Vera Cruz in 1949, Brazilian cinema was in need of a disruption.

The popular images of Brazil in the media at the time were filtered through the United States’ lens, erasing all but Brazil’s tropical elements in order to sell vacations. This was colonial trail left by the Good Neighbor policy passed by FDR after World War II. When France employed guerrilla filmmaking techniques in the Nouvelle Vague, one could say that it was the system fighting the system, a product of nostalgia for simpler times.

In Brazil, the low budget verité aesthetics of contemporary class-struggle films and period epics alike were of an essential revolutionary character. Nowhere is this more obvious than in one of the First Phase of Cinema Novo’s most important films: Carlos Diegues’ Ganga Zumba.

After it premiered in Rio de Janeiro, international critics demanded for it to be added (way past deadline) to Cannes’ Critics Week, where it was the lone film on the week’s eighth day (no word on whether or not The Beatles were inspired by this).

Set in the seventeenth century, Ganga Zumba tells the story of a group of former slaves and their struggle with Portuguese colonial authorities. Like successive New Wave movements, Cinema Novo had to fight colonial structures while simultaneously using their language (in this case, Portuguese) and a visual language indigenous to the cinematic movement.

Opening with stills of violent colonial art, Diegues quickly guides us away from violence to the site of the first democratic revolution on the American Continent. In Palmares, the people have freedom to make love in the mud and engage in personal acts of revolution.

There is a privacy in the film’s aesthetics; many moments, including the aforementioned mud-laden romance, are filmed from bird’s eye view, or like conversations throughout about the authorities’ pending oppressive strikes: in complete darkness.

Beyond telling one of the most important stories in American History, Ganga Zumba is also notable for being one of the premiere historical epics to be filmed in a vérité style, paving the way for films including The Gospel According to St. Matthew, one year later.

Unfortunately, Ganga Zumba and many films from the Cinema Novo movement, in a way recalling the Good Neighbor policy, remain extremely hard to find in The United States. Films this radically political that actively work to rewrite the historical canon are essential viewing, and hopefully Ganga Zumba finds a proper release Stateside soon.

Available to purchase, or in Portuguese without subtitles on Youtube.

6. Daisies by Věra Chytilová (1966)

Czechoslovakia, Nová Vlna

There are conventions and techniques that some of the essential films of the Czechoslovak New Wave share: a penchant for biting satire, mixes of professional and non-professional actors, and sequences that bristle with a sense of spontaneity that is easy to conflate with improvisation.

However, the movement, led by students of the Film and Television School of the Academy of the Performing Arts in Prague, is truly unified by it being a reaction to censorship and oppression at the hands of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. From surreal collages to decadent one-setting dramas, there is great stylistic variety in the movement.

Though the most famous export of the Nová Vlna in the United States is certainly One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest director Miloš Forman, who like many of his contemporaries, fled to the United States following the Soviet Invasion of 1968, the film cited here is from the woman who stayed home: Věra Chytilová.

Daisies, Chytilová’s third film, is a work of both rich color and deep existential dread. Even with its frenzied sequencing and randomly connected insert shots, one thing comes up over and over: Marie (Jitka Cerhová) and Marie (Ivana Karbanová) are looking to do something great, and on their own terms.

One of their favorite squad-activities is taking an old man out on a date, convincing him they both want to run away with him, and then jumping off the train out of town at the last second.

Though it is never boring for us to watch, with a variety of tinted film stocks and the different joyously tricky behaviors the Maries adopt on each dates, they quickly tire of this. Through spontaneous vaudeville routines, dinners made of magazines, and other pop fantasies, the women keep being beaten down by greatness anxiety. That is one of the great pleasures of the film and presumably one of its traits that caused the government to ban Chytilová from making films until 1975.

Patriarchal societies harvest cultures where one has to amount to “something.” Wartime makes fun a thing of disrespect, rather than of release. Upon its release, Daisies was banned from theaters, and 50 years later, its final dedication is still resonant: “to those who get upset over a stomped-upon bed of lettuce, instead of the true injustices happening in the country.” A mind-montage and a celebration, to watch Daisies is to see a diverse garden come into bloom in a fraction of the time.

Available to purchase from Second Run

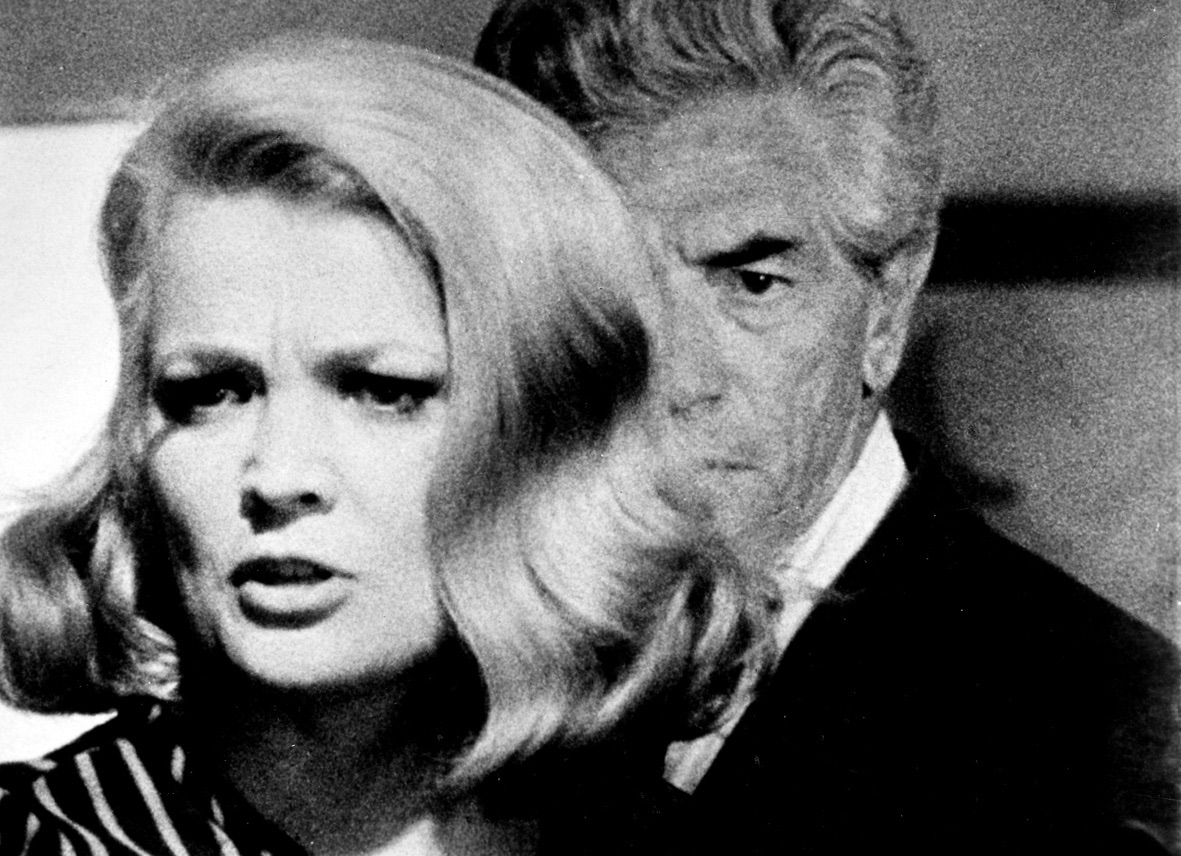

7. Faces by John Cassavetes (1968)

United States of America, New Hollywood

Following the breakdown of the Production Code and a decade of welcome foreign influence from the likes of Sergio Leone, Blow Up, and the stateside popularity of the Nouvelle Vague and Japanese Cinema, directors were put back in charge of the movie business. Traditionally, Bonnie & Clyde, characterized by glamorous violence, Romeo & Juliet stakes, and a resistance to conform to any one genre, is viewed as the beginning of New Hollywood.

Arthur Penn’s film and its plethora of international art house influences (the script was even sent to Godard and Truffaut for doctoring) set the stage for the Spielbergs, Lucas’, and Coppolas of the movement to follow; the directors with a thirst for action and the rhythm of the radio. For the others, the Altmans and the Scorseses, those obsessed with their actors and clapping on the 1 and the 4 just because they can, there was John Cassavetes.

Starting with Shadows in 1959, Cassavetes dedicated himself to doing anything he could (the most notable mythology: maxing out his and several others’ credit cards) to stay out of Hollywood’s grasp. Because of his independence, Cassavetes was allowed to present deeply woven webs of social dynamics and neuroses that played out like the Eric Dolphy to Hollywood’s Glenn Miller.

By the time Faces was released in 1968, at the dawn of the New Hollywood movement, Cassavetes had three films under his belt. Built around character and a stubborn refusal to offer up almost any expository information, Faces is stark and immersive experience that, 50 years after release, leaves viewers as revealed as the characters they are watching.

With its high contrast verité camerawork, symphonic conversations, and claustrophobic blocking, Faces is a kitchen sink drama of an alien degree. The film is centered, as many films of England’s “Angry Young Man” era are, on John Marley’s Richard, a man who has condemned himself to joke his way through life. It is easy to see the influence of Faces and Cassavetes on films from the commercial peak of New Hollywood, such as Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, as well as the later mumblecore movement and the Romanian New Wave.

“Nobody has the time to be vulnerable,” Cassavetes regular Seymour Cassel says to first-timer Lynn Carlin’s Maria during the scene a director other than Cassavetes might have structured as a climax. Indeed, nobody has too much time to be vulnerable, but Faces’ two hour runtime is sure to leave anyone questioning how they communicate.

Available to rent on Amazon.