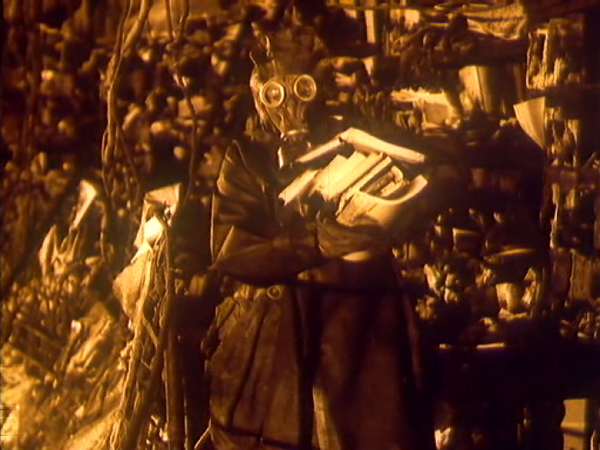

6. Dead Man’s Letters (Soviet Union, 1986, budget unknown)

This post-apocalyptic feature shows people trying to survive after the Bomb has finally exploded and ravaged the world. It was a mixture of human and computer errors what launched the horror, and now people pass most of their time underground, to avoid being affected by radiation.

A group of non- or little-polluted people live in the basement of the former history museum. A man who used to work in the museum doesn’t know where is his son, and writes letters that probably never will reach him.

The story deals not only with the struggle to survive physically, but also with the concern about continuity of culture and civilization. Thus, the location under the museum becomes symbolical and significative. The man who writes letters is appalled at the authorities’ cruelty, that only cares about healthy people and wants to get rid of those affected by radiation. He tries to give hope and purpose to children who have lost any sense of orientation. In the end, he leaves the bunker where he is safe to help those struggling in the surface.

A film not so well known as it undoubtfully deserves, it was the first feature by Soviet director Konstantin Lopushansky. It tackles nuclear disaster in a more radical fashion than most movies about the same topic. In artistic terms, only two other films compare with it in this field: Sacrifice, by Andrei Tarkovsky, and La Jettée, by Chris Marker.

7. Stalker (Soviet Union, 1979, budget Soviet rubles 1 million)

Not a science-fiction practitioner (not even lover), Russian mystic filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky made nevertheless two great pictures that could be labelled as metaphysical science fiction: Solaris and Stalker, both based on great genre novels. Stalker is based on the Strugatsky brothers book Roadside Picnic, but adds to it a spiritual, existentialist dimension.

The “Zone” is a restricted area in an unclear location where spacetime laws have been radically altered after the visit of an alien civilization. It is strictly forbidden to enter it, and the army is in charge of preventing any trespass, if necessary by the use of force. “Stalkers” are guides to the Zone, people who help others to go inside. It is said that in the center of the Zone there is a “Room” where one can express his or her deepest desires and see them fulfilled. To arrive to this room, intruders have to cross mysterious spaces full of unknown dangers, invisible traps that are the consequence of alien presence in the Zone.

A Stalker has arranged to guide a writer and a scientist to the Room: they want to know what it is, experience the fact of being there. During their journey across this cryptic area they discuss many matters, both philosophical and private, and reveal their personalities, but not all their motives to go there. Only in front of the Room will surface all their hidden thoughts.

The film is clearly an existential parable, but the concrete import of the parable is left to the viewer to decide. In this sense, is like a story by Kafka. The best of the film are its haunting images, that remain in memory many years after viewing the film, a cinematography made of long takes with slow camera movements.

The contrast between the Zone and the outside world is expressed through the quality of images: scenes from outside are in sepia, or similar brown monochrome. The music, by Eduard Artemiev (who also composed that of Tarkovsky’s previous films Mirror and Solaris) is superb as atmospheric soundtrack.

No other feature has explored so deeply the existentialist possibilities of science fiction. This literary and cinematic genre lends itself optimally, maybe more than any other one, to philosophical reflection and abstraction, and some films (like most of the included in this post) have gone very far in this path. But the deepening of Stalker into human consciousness hasn’t arguably been reached in any other film.

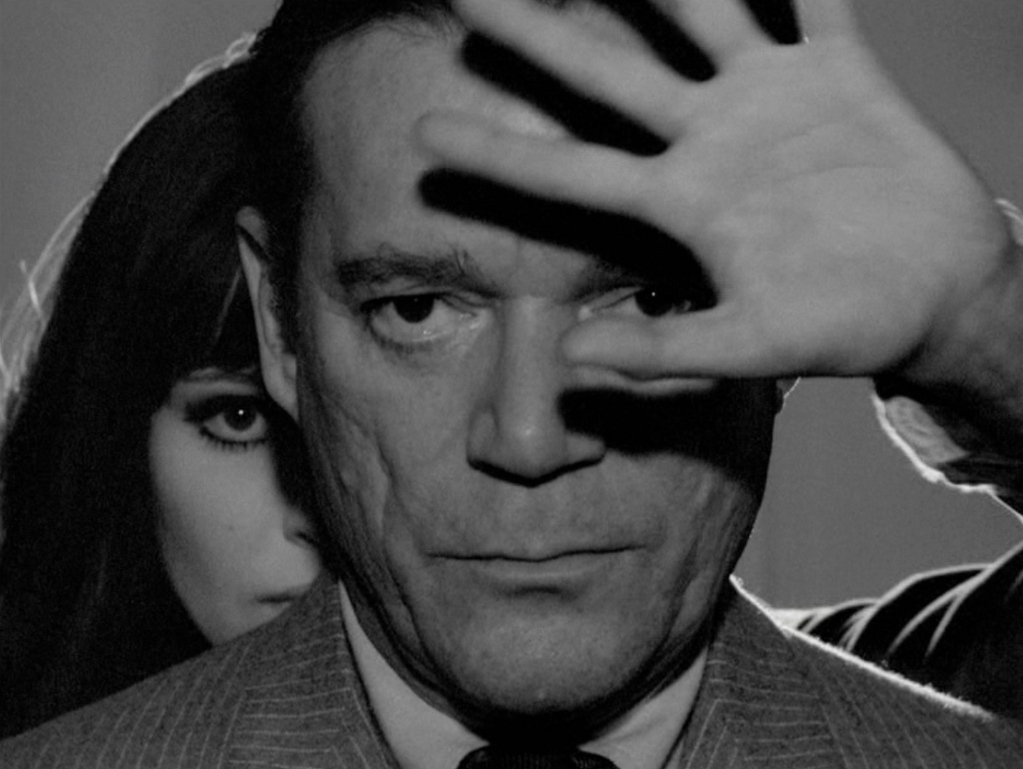

8. Alphaville (France, 1965, budget unknown)

This philosophical dystopia by French New Wave master J.-L. Godard refers, as all the good works from this subgenre, to the present. With no futuristic devices or sets, shot in the contemporary streets of Paris (at night), it shows Alphaville, a nightmarish city absolutely controlled by an authoritarian computer called Alpha 60.

The computer aims to create a machine-like society from which all emotion, love, sense of individual being and art have been suppressed through repression and punishment. A detective arriving to Alphaville from the outside is commissioned to destroy the computer and liberate all the spiritual forces persecuted.

With this scarce, even somewhat childish elements, Godard made a black and white film rich in philosophical suggestions and aesthetic options, all in a tone of avant-garde experimentalism. Nineteen Eighty-Four by Orwell, is clearly in the background, but the cultural references (cinematic and literary) are manifold in this artwork aimed to reintroduce feeling and poetry in a materialistic society that wants to do without them.

9. La Jetée (France, 1962, budget unknown)

Chris Marker, the free radical of French cinema, shot what many regard as the best documentary (or film ) of all time, Sunless (Sans Soleil). Before, he shot many films, among them this black and white post-nuclear time travel featurette (28 minutes), made of still photos: an experimental movie that managed to be not only a rarity appealing to critics and historians, but a story one wants to view once and again, even when the surprise effect of the plot (we won’t spoil it!) has disappeared.

Nuclear holocaust has finally ravaged the human world, and the few survivors of World War III live underground, under Paris buildings. There is a project to send one of the survivors on a time travel to the past and future, in order to find resources to protect present and prevent the utter destruction. The chosen man enters a maze of time paradoxes, revelations about human nature and himself and hopeless conclusions about violence and terror.

Chris Marker, who was a filmmaker, poet, novelist, photographer, videographer and digital multimedia artist, never ceased to experiment in all the forms he practiced, and he even reinvented the form of this forms.

La Jetée exemplifies this permanent search for a language that is new and true and meaningful. Probably only this director could shoot a film almost completely made of still images, with a voice over that tells a story of time travel packed with philosophical musings, and survive. This is, by any standard, a masterwork.

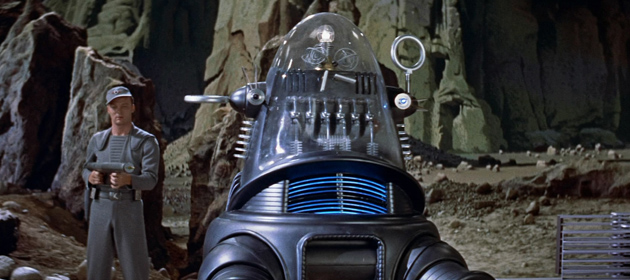

10. Forbidden Planet (USA, 1956, budget $ 1,968,000)

This is a modest B movie shot in Eastmancolor and CinemaScope that started many trends in sci-fi genre. It was one of the first films -if not the first one- to be set on an other planet, in interstellar space, and thus to make human beings travel faster than light speed.

But apart from this adventure aspects, what sticks in mind is a psychological issue. Astronauts arrive to a planet where a scientist (the only survivor with his daughter from a former mission) has been studying a longtime extinguished race of beings of far superior intelligence, whose powers he has been able to preserve and adapt through a device.

Many mysteries from the planet’s recent history -including the disappearance of the other members of the mission in which the scientist was embarked- become explained when the newcomers find out that in the mental faculties of the extinguished race were included subconscious drives and violent passions that Dr. Morbius can activate through his device and transform into cruel forces…