6. Master of Zen (1994) – Brandy Yuen

This film from Hong Kong relates the story of the important Buddhist figure Bodhidharma, who was born in India in the 5th or 6th century. After the death of his father, young Bodhidharma learned Buddhism under the master Prajnatara before undertaking an important mission of his own. He traveled to China for the purpose of spreading Zen Buddhism and finding a successor to carry on his teachings.

Legend has it that, after struggling to find acceptance of his message, he traveled to the Shaolin monastery where he faced the wall of a cave and meditated for nine straight years. After his period of isolation, Bodhidharma taught the Shaolin monks defensive martial arts before returning to India to live out his remaining years. Bodhidharma is a crucial figure in the history of Buddhism, and this film is an outstanding visualization of the events of his life.

The nine-year meditation which Bodhidharma undertook is a primary practice of Zen Buddhism called Zazen. The word Zazen literally means “seated meditation,” and it is the means by which Zen Buddhists realize the liberating insight into the nature of existence which constitutes Enlightenment.

There are no elaborate prescribed techniques involved; rather, one sits quietly and allows thoughts and feeling to pass before the mind as one would watch watch birds fly past against the sky. The ultimate aim of Zazen is, of course, nirvana, which literally means “blowing out” – as of a candle. Nirvana marks the release from the cycle of rebirths for the one whose desire and ignorance has been consumed by the extinguished flame. This is what Bodhidharma sought and taught, and this remains the goal of Buddhist practitioners.

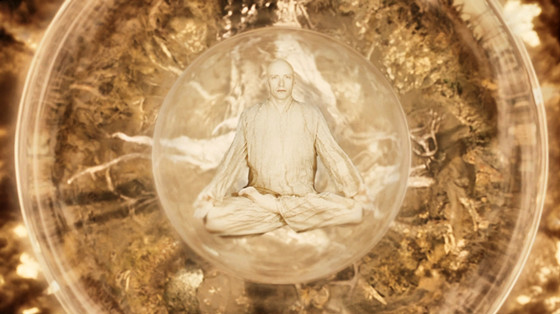

7. The Fountain (2006) – Darren Aronofsky

The Fountain is a unique and at times inaccessible film, but it has much to say to those willing to give it time and focus. With three overlapping storylines which seem to focus on the same characters in different incarnations throughout history, The Fountain demands the viewer’s attention.

Hugh Jackman and Rachel Weisz play star-crossed lovers whose romance is captured in a distant past, a modern present, and an unknown future time. Their journey into the self-knowledge which may unite them again in another world is at the heart of the film. Director Darren Aronofsky created a visually stunning work of art in which the viewer will find it a pleasure to get lost.

The concepts of karma and reincarnation are both integral to the Buddhist system of belief, and they are also closely connected to each other. Reincarnation may be viewed as the effect of karma, which in turn evolves and advances with each reincarnation; this cycle continues until one has shed the attachments, desires, and ignorance which bind the soul with the gravitational pull of physical existence. But karma is not a punishing force to be feared, as one might fear a stalking, tempting devil; rather, it functions as a natural force which simply brings appropriate consequences generated in the wake of actions performed.

Likewise, reincarnation in Buddhism is not seen as an endless journey to which one is condemned for eternity; rather, it is viewed as an opportunity to continually improve and educate the soul until the school of life is no longer needed. These are the ideas which are explored in The Fountain, sometimes obliquely and sometimes explicitly.

8. Zen (2009) – Banmei Takahashi

This film is a biopic of Dōgen Zenji, an important Japanese Zen Buddhist teacher and writer. After being ordained as a monk, Dōgen found disagreements with his order and traveled to China in search of a more authentic version of Buddhism. Upon his return to Japan, he founded the Sōtō school of Zen, and left an extensive body written and poetry.

This is a beautiful film with visuals and a narrative structure designed to enhance its meditative mood. Both seekers and students of Zen Buddhism, which is talked about far more often than it is truly understood, owe it to themselves to watch this faithful account of one the true masters of Zen.

An important element of Zen Buddhism, and a special emphasis of the teaching of Dōgen Zenji, is the belief that Enlightenment may be found near to seeker rather than at some distant point. “If you are unable to find the truth right where you are, where else do you expect to find it?” Dōgen asks.

Therefore, certain principles for right living are prescribed in the Buddhist way of life which are important to understand. The Noble Eightfold Path consists of: right understanding, right intention, right speech, right conduct, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. By performing these positive actions one will lead a noble life.

The five precepts of Buddhism which lay down the code of ethics and morality for its followers are these: abstain from killing or harming living beings, abstain from stealing, abstain from sexual misconduct, abstain from lying, and abstain from intoxication. By observing these rules of training, one will avoid improper actions which create negative karma. These guides of Buddhism are the means by which one may reach Enlightenment, which is an immediate reality and not a remote concept.

9. Ugetsu (1953) – Kenji Mizoguchi

When two peasant men sell for a profit all of the earthenware pots by which they have made their living, a tragic chain of events is set in motion. One of the men pursues wealth and a new love interest, while the other sets off to follow grand dreams of becoming a famous warrior. Both men leave their wives behind with little interest in how their families will be provided for. Each learns some profound lessons along the way, but their lives and families are put in danger of permanent ruin as a result of their selfish actions.

Few films have ever captured the sense of longing brought about by missed opportunities as well as this one does. Discerning the mistakes that are caused by one’s misplaced sense of desire often occurs only after the passage of time, but Ugetsu eloquently frames its story to provide maximum impact to those with eyes to see.

The Four Noble Truths of Buddhism encapsulate the core of Buddha’s teaching, and provide a timeless blueprint for living life. The first one acknowledges the obvious by admitting “this is suffering;” the statement is self-explanatory for conscious beings who are aware of their own condition and of the universal and yet individual pain points of being alive. The second goes further, stating “this is the origin of suffering;” in Buddhism, desire and ignorance are the warp and weft that make up the existential and physical nets of pain in which humans are caught.

The third Noble Truth points out that “this is the cessation of suffering;” logically, the ending of pain in this context would follow the termination of desire and ignorance. The fourth and final Noble Truth expresses “this is the path leading to the cessation of suffering;” identifying this liberating path is the mission of Buddhism, and the finer points of the path are discussed elsewhere in this article.

The two main characters in Ugetsu fail to recognize how their decisions add to their own suffering, and through their misplaced desires they take a road which leads to years of further pain. Only after exhausting the consequences of their selfish actions do they begin to recognize the truth.

10. Metropolis (1927) – Fritz Lang

The influence of Buddhism on this iconic film is easily visible in its plot. The basic story of the film is not new, and may be easily compared to the journey of young Siddhārtha Gautama, who left his life of comfort on the way to becoming the Buddha. In Metropolis, a privileged young man learns of the miserable plight of the workers who run the city in which he lives, and he makes it his mission to help them.

With the aid of an open-minded teacher, played by Brigitte Helm, their efforts plunge them and the city into great chaos, which may be the necessary price for freedom. One of the earliest epic sci-fi movies, Metropolis to this day remains one of the best of its kind. A titanic achievement of vision and ambition, Fritz Lang’s masterwork took a simple, straightforward story and turned it into a massive tale stamped with unforgettable visual and artistic flourishes.

Though the full details concerning the life of Siddhārtha Gautama are unknown or vague, a widely accepted account has emerged and become the traditional standard. Living the opulent life of a prince with three palaces, young Siddhārtha was intentionally sheltered from all knowledge of human suffering.

At the age of 29, he decided to leave his palace to meet his subjects, and thus began his journey toward Buddhahood. Siddhārtha first met an old man, and became aware of the process of aging; next, he passed a diseased man, from whom he first learned of sickness; observing a decaying corpse, he realized the fact of death; finally, he witnessed an ascetic, whose practices intrigued him.

After adopting the lifestyle of an ascetic, Siddhārtha came to believe that such austerities were insufficient to achieve liberating insight. Seating himself under a Bodhi tree, Siddhārtha vowed to never rise until he learned the truth; and, after 49 days of meditation, he reached Enlightenment and was forever known as Buddha, or “The Awakened One.” This is the tale which inspired the story at the heart of the classic epic Metropolis.