6. Videodrome (1983) – dir. David Cronenberg

David Cronenberg’s classic Sci-Fi body horror is a disturbing tale about brainwash and mind-control through extreme violence. James Woods is Max Renn, the president of an obscure TV-channel that broadcasts soft-porn and gratuitous violence. One day he discovers a clandestine television show called Videodrome that airs violent footage of torture and murder. The extreme violence in the footage starts to obsess him even more when he finds out that the hallucinations he begins having are caused by being exposed to it.

Max loses his grip on reality after Nicky, a woman he’s seeing, disappears. Having seen the violent footage from the Videodrome, she decides to participate as a victim in the program. He feels guilty and tries to find out more about the illicit broadcast. His hallucinations are getting worse and he becomes more and more paranoid, descending into a nightmarish state, where he is programmed by VHS videotapes being inserted into his abdomen, his hand transforming into a tumor gun.

The main idea here is that the effect of media violence can be carnal and dramatic. The fascination with violence and its seductive nature have been elaborated later by Cronenberg in his masterpiece “Crash” (1996). Just like the characters in “Crash”, desensitized lust vessels, sexually aroused by car crash sites, Max and Nicky become aroused by the brutal torture performed in the Videodrome arena.

Ironically, Videodrome is created by a fanatic group as a punishment tool for what they consider to be deviants, repeated exposure to it triggering the growth of a malignant tumor in the brain of the viewer.

“Videodrome” is a brilliant metaphor of the way violence and the unverified news lead to the proliferation of conspiracy theories. We see how Max’s paranoia gradually increases throughout the film, the more Videodrome violence he consumes and the more he finds out about it. He is unable to escape the fantasy and becomes an acolyte, totally immersed in the conspiracy.

It’s uncertain if what we see is real or we find ourselves in Max’s hallucinations. We never see him take off the cap that’s supposed to record his hallucinations which Barry Convex, the strange character involved with Videodrome, makes him wear.

Cronenberg induces this state of ambiguity to suggest that the line between reality and fantasy has been erased, that Max has literally become the violence he saw onscreen and is now unable to realize that his actions have consequences in the real world. The onscreen images lure their way into reality, becoming a source of delusion.

7. To Die For (1995) – dir. Gus van Sant

Violence is prime-time, reality talk-show entertainment in Gus van Sant’s classic thriller. The story follows Suzanne Stone (Nicole Kidman), an aspiring journalist who manipulates three teenagers into killing her husband, Larry Maretto.

Ambitious and persistent, her cold beauty fascinating and attractive, she becomes for a short while a media darling. Suzanne Stone is an ambivalent character. The way the story is told makes some of her actions justified without ever trying to make her likable. She knows how to take advantage of her husband’s death and how to orchestrate a good scandal, but the odds turn against her. She becomes the perfect news, but ultimately remains a headline of the past.

The story is told as a reality-show documentary, with focus on the perpetrators. The essence of the reality show becomes the cathartic power of the bad example. The cool eye of the media turns them into typical examples of lost youth, bad seeds, offering them temporary fame and illusory immortality.

The only instances of humanity that the reality show format allows are the baffled, sad looks of both Suzanne’s and her husband’s parents during the funeral and the talk shows they are invited to. The truth is being lost, entangled within the fabricated narrative. As a result, Larry Maretto’s family decides to take justice into their own hands.

The way in which the media deals with violence in this movie is staged, almost theatrical, just like during the husband’s funeral when fluffy, aerial microphones hang over the heads of the mourners like swords of Damocles.

8. Natural Born Killers (1994) – dir. Oliver Stone

“Natural Born Killers” is perhaps the most gratuitously violent movie on this list. However, the violence is being stylized and meant to be fun, the bloodshed wrapped in attractive, shiny packaging and made palatable. “Natural Born Killers” is indeed a fun movie, so much so that you find asking yourself why are you enjoying all that violence so much. This is, after all, exactly the movie’s main concern, namely: why do people enjoy violence to such a great degree that serial killers acquire superstar status?

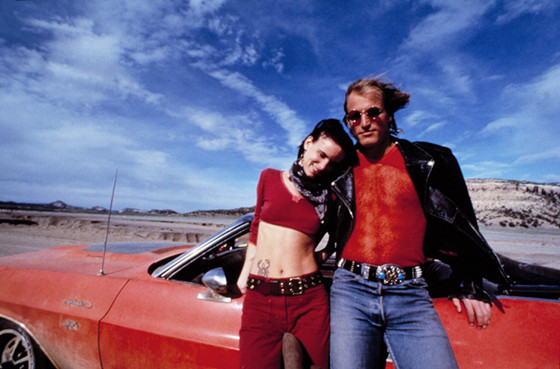

A straightforward criticism of the trash media of the 80s and early 90s, this well-known film is a hypnotic trip. Mickey and Mallory Knox, the “Bonny and Clyde” of the X Generation, are on the run from the police after killing Mallory’s abusive parents. Growing-up on trauma and cheap TV-shows, aggression seems to be the natural response for them.

Oliver Stone leaves little to the imagination. In his film, television unscrupulously feeds on and excretes violence. The obnoxious Wayne Gale, host of “American Maniacs”, a sensationalist news TV-show, becomes the devil in one of Mickey’s visions. Mickey himself turns into the cartooned, media monster he is being perceived as.

9. Funny Games (1997 and 2007) – dir. Michael Haneke

Ambiguous on the pains of human existence with heavy themes and stories delivered mercilessly, Haneke’s movies are among the most analyzed in contemporary cinema. Perhaps his best-known film and the antithesis of the previous one in this list, “Funny Games” is an uncomfortable criticism on media violence. Initially shot and released in 1997, in Austria, Michael Haneke remade the film in the US considering America and the Western world its target audience.

At first glance, “Funny Games” is a home invasion horror film in which a well-off nuclear family goes away to their vacation house to spend the weekend. They are visited by two seemingly polite young men, dressed in white and sporting golf gloves and clubs. Soon enough, the two strange visitors start to torture them for no apparent reason. They make a bet with the family – and with the audience – that the three family members will be dead by the next morning.

“Funny Games” is uncomfortable, violent, but totally exquisite. It’s Haneke’s response to the way in which media and the movie industry has transformed murder into entertainment, especially through the horror genre. The violence here is delivered in a stark, cold manner. Refusing to make it entertainment, Haneke is draining the scene of any excess. No music, no dramatic acting, just the sheer terror of screams and pleas from the victims and the cold, blasé attitude of the perpetrators.

It’s not the first time Haneke discusses the theme of desensitization through the influence of media violence. The chilling “Benny’s Video” (1992), in which a sociopathic teenage boy casually kills his girlfriend, is also a reflection on the effects that the trivialization of violence through media and video games can have on people.

The media (in all its forms: TV, movies, social media) is not just a tool for communication, but has become so superfluous that it makes people addictive. The continuous exposure to violent images is penetrating the human psyche and making people more insensitive to the suffering of others. Screens and cameras are recurring themes in Haneke’s movies, suggesting a mirror in mirror existence where the line between reality and fiction disappears completely.

10. Nightcrawler (2014) – dir. Dan Gilroy

Exquisitely excessive, “Nightcrawler” is an absolutely chilling masterpiece of modern cinema. The main character, Louis Bloom (perhaps Jake Gyllenhaal’s best role to date), is an unemployed, very probably murderous scrap metal collector. Textbook psychopathic, Bloom seems to be doing all this for survivalist reasons. However, the true nature of his personality comes to light when he becomes a freelance videographer who films violent crash and murder scenes on the nocturnal streets of LA.

Although at times excessive and unrealistic, the film discusses themes of moral void, the triumph of ratings over ethics and all-around deontological desert inside newsrooms. People are being served graphic images and hard news at breakfast so that “they’ll talk about it at work”, one staff member says nonchalantly.

Dan Gilroy’s feature looks at the way that news narrative perpetuates stereotypes and deepens existing prejudice, inducing panic and anxiety and keeping people addicted to updates.

The way that news is being manipulated is expressed in what is shown and what not, but also in the way that news is being delivered. For example, there is a subtle difference in the TV-anchor’s voice when she reads news with few or no casualties (linear, almost disappointed) and when she announces accidents with multiple casualties (jumpy and energetic).

Bloom’s blamable methods are not only being overlooked by the media people that pay him for the violent footage, but he is being pushed to deliver ever more brutal and up-close scenes. Bloom’s corporate rhetoric about personal development and career growth he learned on online business courses are funny insertions used to release the tension induced by his shocking and cold-blooded actions. A bleak and distressing view on news media around the world, this post-modern “Psycho” offers no closure.