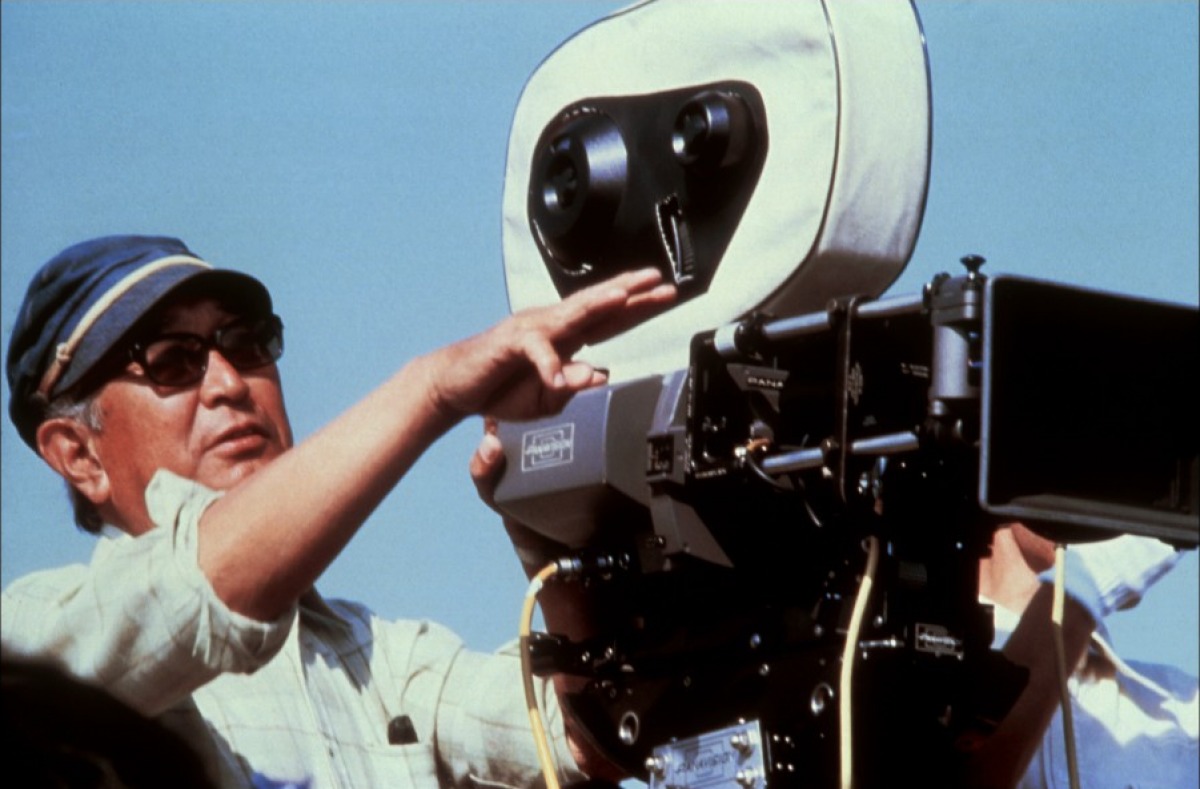

6. Akira Kurosawa

When you look at the modern movie scene it’s hard to deny that Kurosawa has had, arguably, the most prominent influence than any other director. From the way action is shot to the story beats we see of large groups coming together to thwart off an evil enemy, Kurosawa redefined the cinematic language for everyone to follow from that point on. But more than that Kurosawa was a teacher in his native country.

He started out making films in the early 40’s and wasn’t quite finding his voice but in post WWII is where Kurosawa found his mark. His films not only became technically greater, but each followed a similar pattern in his arsenal. Many of his films were set in Japanese lore, samurai in particular is what would become Kurosawa’s trademark. But each film would serve as a bridge between ancient and contemporary Japan.

In the years following WWII America took the lead in occupying and rehabilitating Japan, American forces enacted widespread military, political, and social reform. Kurosawa’s greatest films were being made during this time period and the ongoing themes of rebellion against traditional society in his films were a direct result of the ongoing changes in Japan.

Kurosawa was probably the greatest visual strategist in film history, his direction is what further cemented movement as a central tool in film making and storytelling. Everything that went into his films was the stuff of masters. Whether the characters were moving, the camera was moving, weather was moving on screen, etc. Kurosawa knew exactly what to put on screen and how to use it to greater amplify his story.

Take for example the wonderful scene from “Seven Samurai” in which the father discovers his daughter having an affair with the young samurai. He chases her around feeling she’s dishonored the family, samurais and villagers start to hurdle around creating a feeling of calamity, and as the rain starts to come down everyone leaves one by one leaving the young samurai all alone feeling ashamed for what he’s done.

In one brilliant sequence Kurosawa showed his technique but also the thematic excellence for socially taboo subjects breaking previously held tradition. And that’s only one of many masterpieces of Kurosawa’s legendary body of work.

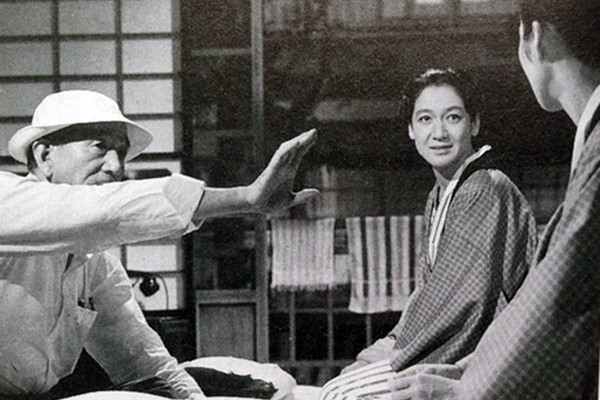

7. Yasujirô Ozu

Roger Ebert once said “Ozu is not only a great director but a great teacher, and after you know his films, a friend. With no other director do I feel affection for every single shot.” And he’s right, Ozu was as masterful a director there’s ever been. He didn’t just make films but rather educational experiences to help us in our ways of life. There’s perhaps no director who’s so eloquently painted pictures of human experience than Ozu.

His films were simple in nature, usually grounded in family dynamics or relationship experiences. But all the while were spiritual examinations through the motions of everyday life. If you go by the old saying ‘with age comes wisdom’ than Ozu is the filmmaker’s equivalent of that. Ozu was never afraid to grow older and as such he made films that aged right along with him that grew with wisdom.

Take his most famous achievements for example: “Late Spring”, “Tokyo Story”, and “Floating Weeds”. Each one is set in the routines of life that can probably happen to anybody. A single daughter taking care of her ill father instead of searching for love, a family who have no time for their grandparents when they come to visit, a father trying to reconnect with his son after so many years apart. It doesn’t matter where we come from because events like these are universal and across the board. They speak to us no matter who we are.

Ozu’s strategies were as simple as they come. His most famous technique was the use of pillow shots, breaking up the events of the story with a shot of something from everyday life. He usually loved boats, trains, empty alleyways, etc. His method was simple, therefore as poignant as possible.

With his films Ozu crafted deeply human stories but made clear of the larger world around them. How industrialization has slowed the ways of human progress as families slowly drift from one another, even if they’re not aware of it. I’m not usually one to get emotional during films, but Ozu is one that I’m not ashamed to admit brings an outpouring of emotion from me. In a lot of ways, he really is a friend once you get to know him.

8. Martin Scorsese

Scorsese was one of directors to come out of the film school generation and, arguably, the best. Hard to say given a lineup including Spielberg and Coppola but in terms of a body of work that has stretched across time there’s no other filmmaker in the modern time period who’s defined the cinematic landscape more than good ol’ Marty. Scorsese was a little kid with asthma in New York, he wasn’t able to play sports or do any kind of physical activities so he just went to the movies as often as he could with his parents.

Scorsese’s love for the movies shines through with just about every film he makes, but more importantly is his upbringing in Catholic beliefs. Catholicism has become an integral part of Scorsese’s brand of content, almost every film he’s made has dealt with Catholic morals and ideology.

Think of the vigilante Travis Bickle punishing the streets of New York for their sins in “Taxi Driver”, Jake La Motta’s hot violent outburst towards his wife Vicky feeling she’s not one of the wholesome religious figures he has up on his walls in “Raging Bull”, the retelling of the story of Christ in “The Last Temptation of Christ”, and the greed and excess that has consumed American culture in “The Wolf of Wallstreet”.

But Scorsese on top of all of that is just a damn fun director, when one watches his films you can’t help but realize how boring and mundane most movies are. Because once you watch of one Marty’s masterworks the screen just comes alive and pulls you along for a journey.

Much of his signatures are likewise the result of the people he holds close to him. His frequent collaborations with actors like De Niro, Pesci, and Dicaprio, his long-time friend and editor Thelma Schoonmaker, his screenwriting partners like Paul Schrader and Nicholas Pileggi, etc. All of which are deservingly talented but likewise share that same artistic integrity Scorsese holds and stop at nothing less to fulfill his visions.

9. Andrei Tarkovsky

Andrei Tarkovsky was a director like none other. To watch his films felt more like a meditation than anything else, what’s structurally most fascinating about Tarkovsky’s work is that his films consist mostly of telling. In that there’s no real story to unravel, there’s only the experiences of witnessing the events first hand. If there is or was a story somewhere it’s long gone because time, space, and everything in between flows in a pace that bypasses our abilities to see something in recollected hindsight.

Some might call his films boring, and who am I to tell you how to feel, but when watching his films (or any film in general) we as an audience have two choices: We can be bored with what we’re watching, or we can observe what we’ve seen up until this point and decipher why we’re where we are and what’s ultimately the endgame of what we’re experiencing. And hopefully you make the right choice.

Tarkovsky’s films work as manifestations of humanity’s lifespan. They provoke us in the most existential ways possible that do nothing less than meditate on human conditions.

Philosophy and spirituality interweave his grand methods, so much so that he had to exile his native country after Soviets authorities disregarded his films. But no matter how much they may have tried to cut his films down Tarkovsky still stands tall, they were as ambitious and profound as any great work and never concerned themselves with what anyone else would’ve wanted. He made films as he saw them, something that a lot more directors should do.

With films like “Andrei Rublev”, “Solaris”, “The Mirror”, “Nostalgia”, and “The Sacrifice” you might watch a lot of ‘boring’ dialogue and lingering shots, but Tarkovsky had a way of using this to draw out time. Nothing was ever rushed along because of anyone’s desire for it, it only comes about through earning what it has to say. Only then does his films take full shape, and now characters and developments are made into the light that he envisions them in. We just have to put in the work for it as well.

10. François Truffaut

Here’s a hypothetical scenario: you watch a movie that’s bad and you say to yourself “I can do better than that.” Long story short that’s essentially what the French New Wave was, film critics who were bored of what they were watching so they took matters into their own hands.

Post WWII French films, according to these critics, wasn’t giving France its own national identity. Most films weren’t tackling feelings that were happening in the country at that time. That’s not to say there weren’t great films being made, far from it, but the New Wave was made differently.

Truffaut, as well as others, were making things on location and were taking more chances with experimentation than ever before. Editing was different, films were shot more like documentaries, and narratives were told much differently in order to reflect the current feelings of France during the 50’s and 60’s. Through his career with the magazine “Cahiers Du Cinema” Truffaut learned how to make and finance his films independently, and then he was off.

Truffaut once said “I demand that a film express either the joy of making cinema or the agony of making cinema. I am not at all interested in anything in between.” His works reflect this in spectacular ways. His most famous of course being “The 400 Blows” a film that takes the concepts of adolescence and shows exactly how lonely and depressing it can be.

But by that same notion he could tone up the joys he had of filmmaking with entries like “Shoot the Piano Player” in which he makes gangsters more comedic in nature because he realized he didn’t like gangsters. His craft became apparent overseas as he was meant to bring his ways to American cinema with “Bonnie and Clyde” but ultimately turned it down. Still though this doesn’t remove the mark he left on film as a whole around the world, as today everyone still basks in the impact Truffaut left in the cinema.