5. The Fountain (2006)

A psychedelic sci-fi fantasy and a historical romance that miraculously maneuvers multiple meanings, ideas, themes, and storylines in an epic triptych that spans a thousand years, Darren Aronofsky’s The Fountain centers on the celestial space pursuance of everlasting life represented in a mythical tree.

Starring Hugh Jackman in three roles; as Tomás Verde, a 16th-century Spanish conquistador; Tom Creo a 21st-century neurologist; and Tommy a space traveler in the far future en route to the golden nebula of Xibalba, each fighting to save his beloved (Rachel Weisz) from death, The Fountain takes the biblical tree-of-life from the Book of Genesis and Kabbalah. There’s also a gripping through line binding neuroscience and Spanish colonialism as well as Mayan myths glimpsed from an indigenous lens, and a playfully profound intermingling of David Bowie’s “Major Tom” pop chronicle.

Matthew Libatique’s stunning cinematography gives The Fountain its most immediate pleasures, presenting an often floating camera-feel that helps the ethereal elements appear more palatable as in the meticulously detailed and beaming bright with candles 16th-century Spanish court or the darkened yet intricate chambers of the fanatical zealot Grand Inquisitor Silecio (Stephen McHattie) where a gold-lit fringe dazzles with a Bosch-like lucidity.

The Fountain should be forgiven its poetic flourishes and ambiguous angles as the most important point of the film is irrefutable; it looks like a miracle.

4. Under the Skin (2013)

A deeply thoughtful and profoundly shocking exploration of civilization and humanity, Jonathan Glazer spent nearly a decade on this dark hearted epic, Under the Skin. Comparisons to Stanley Kubrick and Andrei Tarkovsky are appropriate and easily supported, as are the carefully constructed visual sensibilities and quasi-documentary leanings of Claire Denis and Lynne Ramsay. Loosely using Dutch author Michel Faber’s satirical 2000 sci-fi novel “Under the Skin” as the alpha of this deep, metaphysical and mercurial treatise on humanity, Glazer has surpassed expectations.

Scarlett Johansson is outstanding, shining in a controlled and calculating process as she moves from childlike cherub to rouge-lipped iconoclast, all while saying very little. Seducing working-class blokes at random, she lures them into her alien lair with terrifying and deeply troubling results. Her motives remain unclear in what amounts to an unaffected nightmare.

Mica Levi’s score adds heft to Glazer’s artfully arranged visual compositions, culminating in a third act extravaganza of upset and intrigue.

An elaborate subterfuge of a film, ethereal and arty, Under the Skin is an unnerving, unpredictable, and sense-rattling experience that will alternately haunt and reward the patient viewer for days afterwards. Under the Skin does just what its provocative title promises, make no mistake. It’s also something of a masterpiece.

3. Hard to Be a God (2013)

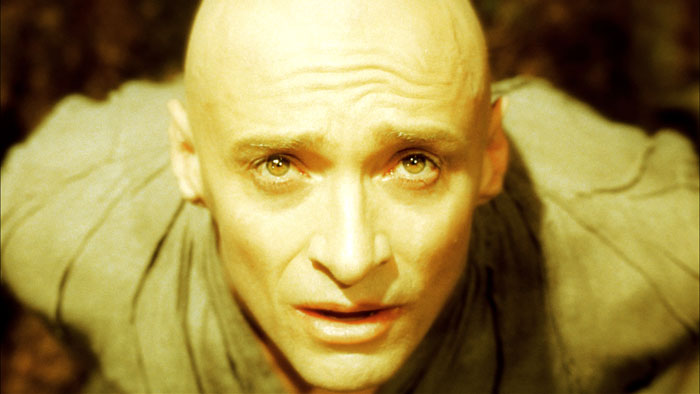

The long-gestating final film from Russian cinema heavyweight Alexei Gherman (My Friend Ivan Lapshin [1985]) spent decades in pre-production, was begun in 2000, filmed over a six year period, spent years after that in post-production, and was finally finished posthumously by Gherman’s son, and released theatrically in 2013. Hard To Be a God is that rare reward of visceral cinema, and an epic in every sense of the word.

Adapted from the underground sci-fi cult novel by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky –– the sibling duo who penned “Roadside Picnic”, the basis for Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979) –– Gherman’s crowning achievement takes place on an alien planet Arkanar, eerily like our own only here the Renaissance never happened, resulting in a never-ending Middle Ages nightmare.

Shortly after I’d seen a wondrous 35mm print of Hard to Be a God at the Cinematheque in Vancouver, Canada, I had the good fortune to visit the Getty Museum in Los Angeles during an exhibit of Hieronymus Bosch’s work.

The medieval master’s unexpected imagery, dripping with macabre detail of hellish landscapes, fantastical and freakish figures, and startling religious narratives with cruel men and demonic beasts often adorned with halos or the twisted maws of damnation; here did I see with bracing clarity what Gherman and his gifted dual cinematographers Vladimir Ilyin and Yuri Klimenko were going for with Hard to Be a God. Their richly detailed black-and-white cinematography recreates Bosch-like tableau and Brueghelian details of barbarity, beauty and grotesque human contest. If a more immersive, ingrained and extravagant film than this exists, I’ve yet to see it.

2. Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)

George Miller’s Mad Max: Fury Road offers up so much eye candy in the ultimate chase movie as he retools the motorcade mayhem first glimpsed in The Road Warrior (1981), the first of his Mad Max sequels. Riding shotgun with Miller is his astonishing editor and wife Margaret Sixel who helps clearly define for the audience the spatial relationships of the many elements –– vehicles, characters, etc. –– specifically the crazy quilt cause-and-effect maneuverings of fast-paced and ever-moving mayhem. The physics of action cinema have rarely if ever been so pronounced and so awe-inspiring.

The post-apocalyptic cosmology of Mad Max: Fury Road is also augmented by Colin Gibson’s alternately gorgeous and grotesque production design, Jenny Beavan’s costumes, and John Seale’s in succession trembling and tranquiil lens. Any way you cut it, Fury Road is a genre fan’s fantasy fully realized and a pièce de résistance writ courageously large.

1. Blade Runner 2049 (2017)

Working closely with the screenwriting team of Hampton Fancher (who co-wrote Ridley Scott’s original Blade Runner back in 1982) and Michael Green, as well as his sensational cinematographer Roger Deakins, visionary Canadian film director Denis Villeneuve (Arrival [2016]) did the near impossible task of following up Scott’s Blade Runner with a sequel that retains much of the tactile splendor and future noir poetry of the original while manufacturing an objet d’art that is perhaps even more emotionally engaging.

Unspooling some thirty years after the first film, Ryan Gosling is K, a replicant who hunts rogue replicants and, like Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) before him, retires his quarry using deadly means. When K discovers evidence suggesting that a replicant has reproduced and had a child, he is charged with murdering the child to prevent a replicant uprising.

A sublimely articulated mindbender, seductively crafted, steeped in mystery, and one that teases the audience with numerous ambiguities, and needling puzzles, Blade Runner 2049 is one of speculative fiction’s crown jewels. This is a film that, like its predecessor, will be discussed, dissected, revisited and extolled for decades to come. Sci-fi so rarely gets this ruminative and magnificent. Not to be missed.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.