10. American Hustle

With all due respect to The Wolf of Wall Street’s opening—replete with an actual commercial made by its real-life subject matter, dwarf tossing, and Goodfellas-reminiscent voiceover—no 2013 film could top American Hustle’s opening. There’s a retro studio logo, then a fade to black followed by the words “Some of this actually happened”, which works as a boffo rebuff to an industry that is happy to option true stories and twist the truth out of them for the sake of plot structure and Oscars. Cut to Christian Bale, at the height of his Batman-powered star status, looking paunchy, bald, hung-over, and worse for wear.

The scene then takes its time as Bale teases out his hair, massages and finesses it into a convincing combover, and sprays it into place. The scene goes on for minutes, with Bale’s supreme focus and some background jazz the only things keeping the audience in place. When he finishes, he goes out into an adjacent room, where his costars and the rest of the movie is unfolding in a panic.

We’ll come back to this scene, but the drawn-out primping we’ve just witnessed tells us everything we need to know about the character and the movie. It’s strange. It’s deceiving. It’s a facade based on appearances, and it’s a total blast.

9. The Social Network

At the end of the 2010s, The Social Network was assessed as one of the defining filmic efforts of the decade largely because its subject matter had become such an influential, pervasive entity. The Social Network has myriad issues, but its beginning and ending are among its decade’s best. Aaron Sorkin’s script imprinted a trite Hollywood sensibility (nerd wants to be cool and overcompensates) to an infinitely more complicated and menacing reality (the rise of a disturbingly powerful corporation with no social concerns and infinite opportunities to surveil and control), while David Fincher’s immaculate, sterile style turned its subject matter’s detachment into primo substance.

When these sensibilities matched, the film soared, and the opening scene was one of the best examples of this. Jesse Eisenberg’s interpretation of Mark Zuckerberg talks at his soon-to-be ex at lightspeed, his clipped cadence and unwillingness to slow down communicating everything the script wants us to think about its anti-hero. This is essentially a breakup scene played as origin story, and while Eisenberg got the Oscar nomination, it’s Rooney Mara who walks away with the scene and the soul of the film. The Social Network ends with a cloying but effective metaphorical act of contrition, but it’s the opening scene’s precision, right down to the rapid-fire dialogue, that makes the overly romanticized saga of greed, ambition, and cunning seem as deeply felt and engaging as it is.

8. Citizenfour

If The Social Network was about making fiction from truth in order to comment on the human condition, then Citizenfour might be about the opposite: dissecting the lies of governance to expose the truths that will dictate our future. Few films have as much of a claim to the title of “Most Important Film of the Decade” than Citizenfour, Laura Poitras’ explosive, incredibly well-timed, and intimate chronicle of Edward Snowden’s revelations. The film unfolds in real time and, in an unprecedented coup of filmic journalism, captures one of the most important episodes of the decade practically as it happens.

Given the scope and implications of its content, it’s easy to overlook how accomplished and nuanced Poitras is as a filmmaker. One of the United States’ most important post-9/11 chroniclers of the new world order, she opens her film with a tight introduction of the government surveillance she has faced before launching into a voiceover that recounts Citizenfour’s efforts to get in contact with her.

Using a black background and relying only on her voice to read out real correspondence, lines like “this I know to be true” resonate with the full weight of their implications. There is an elegance to the way such important matters are handled without hyperbole or dramatic flourish. Poitras was one of a handful of journalists that made history with Snowden’s revelations, but she also deserves to be considered one of the foremost storytellers of this century.

7. Ingrid Goes West

So many films have tried to capture spirit of online culture and communication with such hilariously embarrassing results that Ingrid Goes West’s opening scene might be a mini miracle. Using the aesthetics of influencer culture, some hyper splice editing, and excellent comedic timing, Ingrid Goes West delivers an opening scene that is acerbic, funny, and concisely informative about where it’s going to go and how it’s going to get there.

Ingrid Goes West opens by blasting through the social media history of one of its characters before launching into a wedding. Ingrid is there to offer a conflict of sorts. Awkwardness, to put it lightly, ensues. The scene functions as a precursor to a larger story, one that happens far away, and were the filmmakers merely setting up an internet-themed bunny boiler, the scene would be good enough.

But Aubrey Plaza inhabits her character with a lived-in sensibility and affection that signals that she’s not interested in laughing at Ingrid, and the story has an eye for the ugliness of the human soul that manages to speak to larger themes without being pedantic. Ingrid Goes West makes some strange choices that aren’t always fulfilling, but its opening is shows its best attributes: it’s sharp, unsettling, and to the point.

6. Birdman/The Revenant

Alejandro González Iñárritu was awarded consecutive best director Oscars for his two mid-2010s efforts. The Revenant, one of the decade’s most beautiful films, opens with a poetic dream-like sequence of star Leonardo DiCaprio’s character at rest with his family before gently segueing into a mini-battle between the trappers and Native Americans increasingly at odds over the land. It’s a bravura opening that kicks off a film full of them. The Revenant rubbed many the wrong way, but it’s hard to deny its craft.

Strangely enough, for all the technical brilliance and immersive qualities of The Revenant’s opening battle, it might Iñárritu’s previous effort by one year, Birdman (Or the Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) that actually has the stronger beginning. We see Michael Keaton’s faded movie star meditating in his tightie whities. But more than meditating, he’s levitating. An asteroid falls to earth. We’re instantly inside a superhero epic then back to a Hollywood satire.

Birdman will zigzag back and forth while also dipping into the character drama of Raymond Carver and the magical realism that would also play into his next film. It’s a wild opening that bubbles with the energy and tension a dozen other films would struggle to match.

5. Baby Driver

The 2010s was the decade where the industry finally and formally acknowledged the importance and artistry of the needle drop. And just like that, Edgar Wright’s Baby Driver threw down the gauntlet with a car chase so well executed that it immediately entered the pantheon of great stunt work. In a decade where the strongest, most action-heavy franchises consistently outdid each other, the simple pleasure of a heist getaway managed to outshine most of them.

Part of what makes Baby Driver’s opening set piece so impressive is that it has so much heavy lifting to do. Some of the most intricate opening sequences of the decade came from established franchises—Mission Impossible, James Bond, John Wick, the Fast and Furious movies—but Baby Driver literally starts from scratch with little more than a bit of star power (hindered by Kevin Spacey’s #metoo disgrace) and a killer soundtrack.

Anchored by The Jon Spencer Blues Explosion’s Bellbottoms, Baby Driver’s initial post-heist escape through Los Angeles gets the engine going. The character’s dexterity and cunning are matched by Wright and his crew, who stage the piece with such wild aplomb that their joy is contagious. The scene almost threatens to run away with the rest of the movie, but Wright understands that this is the scene that’s meant to dazzle the audience into accepting the bitter fantasy that comes next.

4. Cartel Land

According to director Mathew Heineman, he didn’t set out to make a conflict zone documentary with Cartel Land (that would be his second feature, City of Ghosts). Regardless, his film literally takes him and the audience into the middle of gun battles and militia warfare. It’s a testament to his film’s timeliness that what began as an exploration of minutemen at the US-Mexico border turned into a saga of drug violence and the citizen militias fighting back against the cartels.

The access Heineman gets is among the film’s most impressive feats. He puts the audience face-to-face with the victims and perpetrators of drug gang violence. The opening scene, the difficulty of which has been documented, is a haunting and informative triumph of reportage. Heineman gets up close and personal with the meth cooks whose products fuel so much suffering. The interviewees may be masked, but they are exceptionally candid, and the things they have to say reorient these issues for what they are: the ravages of supply and demand economics coming right up against the limited economic opportunities that make the drug trade so attractive to so many.

Social significance aside, the opening shot is eerie, beautiful, and terrifying. Heineman is meeting people we describe as monsters, and the suspense of the situation radiates off the screen. It is tense and suspenseful in a way that even the tightest thrillers aren’t. Cartel Land is one of the most suspenseful films of the 2010s, and its opening scene plays like a nightmarish real-life embodiment of Breaking Bad.

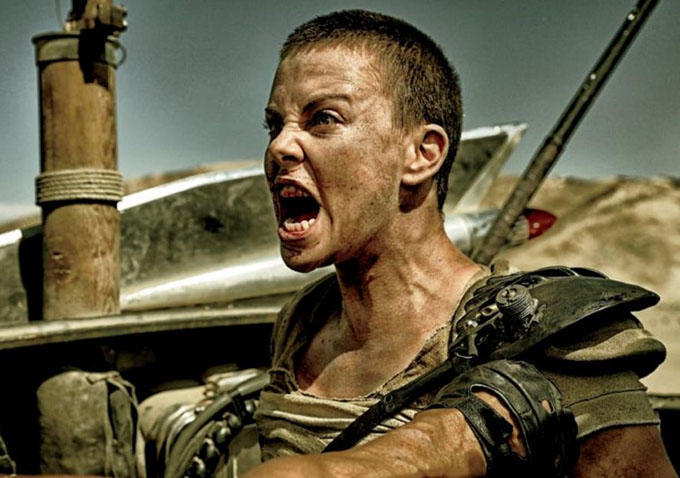

3. Mad Max: Fury Road

What a strange, kinetic surprise Mad Max: Fury Road turned out to be. So undeniably good that even the Oscars couldn’t ignore it, Mad Max: Fury Road made a case for cinema as spectacle, for action as story, for getting out of the way and letting the medium do its work. In an age of sequels, reboots, and staccato franchising, George Miller wisely understood that those things don’t have to matter.

Continuity is addressed in a couple of lines at the beginning. The re-casting of the main character, and all the baggage that might’ve accompanied it, is utterly irrelevant. Worried about decades of hackneyed dystopian rip-offs making any continuation of the Mad Max story unnecessary? Well, Miller isn’t. The result is glorious.

We open with a brief nod to the past before cutting to our protagonist looking over a bad scene. It isn’t long before he’s given chase and finds himself at the mercy of a society that treats men as blood bags and women as sex slaves while dousing its scorched denizens in rationed water supplies.

The world of Mad Max: Fury Road is ugly, but the way it’s displayed is beautiful. Sun-choked landscapes and cragged cliffs are an ideal canvas for the vivid reds and oranges that color the film’s lensing. Miller stages Max’s capture and near escape with an operatic fervor timed to hilarity. Critics and audiences went gaga over Fury Road when it was released and again at the decade’s end. When things are this artful and this fun, it’s not hard to see why.

2. Wild Tales

Including Wild Tales might seem like a cheat considering that it’s an omnibus film consisting of multiple standalone stories united primarily by the theme suggested in the title. By this logic, Wild Tales opening scene is an isolated story with limited relevance to the rest of the film. Still, anyone who’s seen the film can attest to the wit and efficacy with which the opening story, titled “Pasternak”, sets up the rest of the film while hooking the audience with its dark humor and riotous storytelling.

“Pasternak” takes place entirely on an airplane, with two passengers discovering a surprising shared connection. From there, the sequence sparks a sense of dread that builds to an explosive conclusion that tips over into lunacy before cuing the opening credits. To say more would rob unsuspecting viewers of the madcap charm of Wild Tales, which imbibes every segment with organic drama and rollicking insanity.

Each segment in turn builds anticipation for the next, with each story offering some cutting observation on societal mores and injustices. It’s the opening that sets the stage while whetting our appetites. Wild Tales is a film in which almost anything seems possible, and Pasternak establishes that brilliantly.

1. Melancholia

Lars von Trier spent the first part of the decade acting like an asshole and the latter part largely shunned because of it, but with Melancholia he made the most audacious opening scene since 2001: A Space Odyssey. Melancholia even functions as a sort of companion piece: 2001 showed the dawn of an age; Melancholia destroys the planet in its opening scene.

Fully cognizant of the ridiculous gravity of his story, von Trier oscillates from the immense—shots of celestial orbs waltzing and ultimately smashing into each other—to the personal—Kirsten Dunst walking towards oblivion in her wedding dress—until sparks literally fly from Dunst’s fingers. Melancholia was von Trier’s middle entry in a trilogy dealing with depression and decay, but in a career defined by controversy and a willingness to scan the depths of human pettiness with equal parts glee and detachment, Melancholia stands as a masterwork by a master momentarily at the height of his powers.

Opening scenes have certain obligations—world building, attention grabbing, scene setting—but every so often a film comes along that at once plays with cinematic grammar and leverages our expectations of what art, commerce, visual media, and sensory stimulation can do. As part of a pack of provocateurs whose work strained to remind audiences of the inevitability and beauty of destruction, von Trier’s work in Melancholia’s opening moments is the epitome of this truth.