17. Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019)

French formalist writer-director Céline Sciamma (Girlhood) is completely in her element with her exquisitely tender costumer, the laudable and lovely new film Portrait of a Lady on Fire. Having already achingly smouldered earlier this year at Cannes where it rightfully netted the award for Best Screenplay, Sciamma’s painterly perfection focusses on Marianne (Noémie Merlant) a 19th-century painter commissioned to a lush island home to paint the wedding portrait of ravishing young Héloïse (Adèle Haenel).

The deeper that Marianne and Héloïse sink into their foreordained love the more their world seems to feel like tragic symbolization, and the film is gorgeously lit to look like Neoclassical paintings from the era.

Seductively shattering and intimately breathtaking, Portrait of a Lady on Fire may leave certain aspects of these women’s deeply partaken love as emotionally unresolved, but it’s all so swooningly photographed, magnificently acted, stirringly told, and with a tone so close to illusory––as such it’s quite stunning.

16. Melancholia (2011)

There’s a certain je ne sais quoi about Lars von Trier’s hypnagogic and deeply pensive apocalyptic powerplay Melancholia that cinches it as one of the director’s very finest motion pictures. For one, it’s so rare a thing that a film capture with such startling insight and due diligence the emotional state that depression casts upon the individual, and for anyone who’s wrestled with that black dog they can easily see the naked truth in Kirsten Dunst’s chef-d’oeuvre central performance as Justine.

Melancholia playfully and profoundly upends sci-fi convention in a tense and dangerous spring-loaded narrative that pivots around newlyweds Justine and Michael (Alexander Skarsgård). These ill-fated lovers tie the proverbial knot just as the world at large learns of the presence of a rogue planet, “Melancholia”, which is believed to be on a near-collision course with Earth and will most certainly be an extinction level cataclysm.

Led by Dunst’s luminous performance, ably backed by Charlotte Gainsbourg as her sister, Claire, both hanging on the speculations and suspicious that the End of Days might not be so dour for everyone. The film also presents a formal elegance resulting in a lushly unforgettable bookend of astonishing and shocking visuals. An absolutely unforgettable showpiece.

15. Toni Erdmann (2016)

Pathos and playfulness make for admirable bedfellows in German writer/director Maren Ade’s sprightly pièce de résistance, Toni Erdmann.

Estranged father Winfried Conradi (Peter Simonischek) is an aging bohemian with penchant for elaborate practical jokes. Winfried, also a divorcé and retired music teacher, is greatly distressed following the death of his little dog, Willi, and decides to make a surprise visit to Bucharest to see his daughter, Ines (Sandra Hüller), a reluctant workaholic corporate hot shot.

Winfried, donning a cheap disguise consisting of a bad wig and false teeth creates the ambitious persona: ‘Toni Erdmann’, life coach. Will his spontaneous visit bring a holy mess to his daughter’s distracted world? You betcha.

Toni Erdmann has a lot on its mind, and Ade is a director of great intelligence, and one well versed in abrupt instants of audience blindsiding and many modes of humor from gross-out gags to surrealist circumvention.

A dazzling comedy of modern life’s illogicality, a bold feminist statement, a touching family drama, and more, Toni Erdmann is proportionately disarming and charming and one the most ambitious films thus far this century. Wow.

14. First Reformed (2018)

From its brilliant use of subjective camera, and the dazzling 1.37:1 aspect ratio––almost like a religious painting from the Renaissance––First Reformed uplifts the mind to the spiritual as writer-director Paul Schrader exhibits the transcendental style he’s always been capable of but rarely it seems, ever extolled.

Set in a small town in upstate New York, the First Reformed church is about to usher in its 250th anniversary as Reverend Ernst Toller (Ethan Hawke, absolutely brilliant in a career best performance) begins a diary. Toller’s life in a secular world is darkened by his tortured past that includes the loss of his son in the Iraq War, his numbing and secretive alcoholism, and his failing health, both physical and mental.

Astonishingly unified in both its style and its subject, First Reformed is a glorious and gratifying work of artistry that attains the ecstatic as well as the divine. Schrader has, as in Robert Bresson’s own films, evoked and embodied that Pascalain paradox that God is both invisible but present. And also like Bresson, Schrader lays bare the work of a master filmmaker who is both unflinching social critic, and generous spirit-guide.

13. Parasite (2019)

Korean filmmaker Bong Joon Ho is back and more brilliant than ever with Parasite, his so-very-deserving Palme d’Or-snatching socio-political critique that goes from slapstick comic hijinx to outright angry class rage and back with alacrity and ease.

Co-written along with Han Jin-won, Bong presents a full-flavored bravura delicacy about a family of four, the Kims, under very dire circumstances. They struggle to remain just above the poverty line in a slipshod semi-basement apartment, and as the early scenes of Parasite enumerate, often rather amusingly, they’re a greed-driven yet extremely resourceful bunch.

Equal parts artful and urgent, Bong’s masterful pisstake on class politics (after and even before all the blood and thunder, just who exactly are the eponymous parasites?) is a dark thriller loaded with laughs as well as a socially astute melodrama. Like his finest work, and Parasite easily ranks alongside Memories of Murder (2004) and Mother (2009), this is a film that defies easy genre-classification. Here the shifts of tone and sometimes breezy bits of horseplay often startle with stabs of frenzy and sorrow.

12. Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)

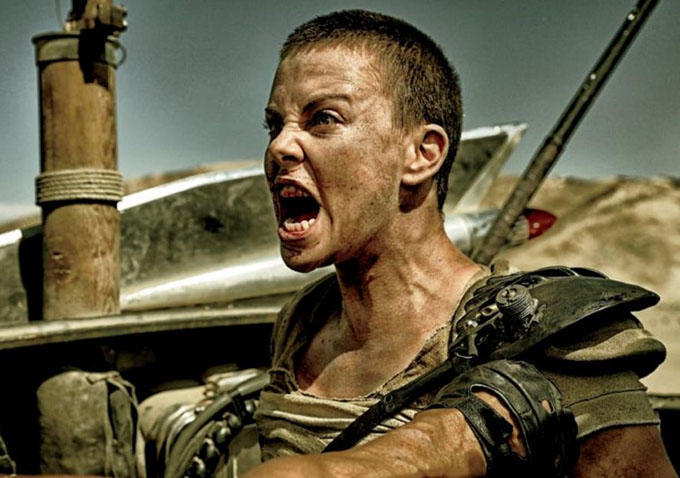

George Miller’s Mad Max: Fury Road offers up so much eye candy in the ultimate chase movie as he retools the motorcade mayhem first glimpsed in The Road Warrior (1981), the first of his Mad Max sequels. Riding shotgun with Miller is his astonishing editor and wife Margaret Sixel who helps clearly define for the audience the spatial relationships of the many elements––vehicles, characters, etc.––specifically the crazy quilt cause-and-effect maneuverings of fast-paced and ever-moving mayhem. The physics of action cinema have rarely if ever been so pronounced and so awe-inspiring.

The post-apocalyptic cosmology of Mad Max: Fury Road is also augmented by Colin Gibson’s alternately gorgeous and grotesque production design, Jenny Beavan’s costumes, and John Seale’s in succession trembling and tranquiil lens. Any way you cut it, Fury Road is a genre fan’s fantasy fully realized and a pièce de résistance writ courageously large.

11. The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)

Martin Scorsese’s lascivious and exhilarating The Wolf of Wall Street, is a pitch-black comedy that chronicles the rise, fall, and rebirth of real-life New York stockbroker Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio) during the late 80’s and early 90’s. Based off of Belfort’s memoirs, it’s obvious right off the bat, as DiCaprio talks directly into the camera, that this is a somewhat biased, altogether lecherous, and unreliable narrator whose greed is matched only by his grandstanding.

As Belfort, DiCaprio gives one of his best ever performances as a nasty, bellicose douchebag. Belfort begins at the bottom but soon cheats, swindles, and sneaks his way into the big leagues with his brokerage firm and cadre of money-worshipping accomplices, which include Donnie Azoff (Jonah Hill), Nicky “Rugrat” Koskoff (P.J. Byrne) and more Quaaludes and coke then you can conceptualize.

It’s all a fast-paced film, teeming with nudity, f-bombs, endless drugs, and populated wholly by reprobates, these ridiculous and grotesque criminals deserve their undoing. All told, The Wolf of Wall Street is an elated and unruly howl.

10. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019)

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is Quentin Tarantino’s love letter to Tinseltown, albeit one inked with a poison pen. Atypical of QT, this is a giddy grab bag of pop culture references and playful allusions to Hollywood’s past and potential futures.

Unraveling in 1969, just ahead of the New Hollywood movement that would forever alter the film industry, the film focuses on three forlorn characters; Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio), a fading Western TV actor having a simultaneous midlife and identity crisis trying to make it in the movie business; Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt), Dalton’s stunt double and BFF; and then most ill-starred of them all, Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie), the real-life rising star whose life and career were cut short most tragically on August 9th, 1969, at the hands of members of the Manson Family.

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood presents us with characters in a special and very specific place and time. Maybe nothing much happens over a few days in February but the play of light and the spatter of shadows suggest that summer and August in particular, hold something sadly significant and terribly, terribly wrong.

9. Roma (2018)

“A majestic feat of filmmaking,” writes Globe and Mail critic Barry Hertz, calling Roma “an intimate portrait of a family that also serves as a broad portrait of a changing nation.” And so Mexican filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón at long last has his masterpiece with Roma. And it is an abundantly textured treasure at that.

A beautifully rendered black-and-white tale (Cuarón also photographed the film) of a household in the middle-class Colonia Roma neighborhood of Mexico City in 1970. Here we get to know live-in maid Cleo (Yalitza Aparicio, brilliant) who tends to four young children.

As Clea, whom Cuarón named after the title character in Agnès Varda’s Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962) not only cares for the children but cleans, cooks, and quietly observes, she witnesses her employers’ marriage disintegrate. Cleo’s own love life, too is fraught and fragile, and the film, which spans a year, depicts both pained and precise events in the shared domestic space, and also to the wider tensions in society at the time; idyll pleasures––going to the cinema, a roadtrip to the country, an initially curious reference to martial arts training from a potential suitor––take on a darkened hue as the turmoil shaping within the country is further examined.

A subtly and grace shade these details that eventually pulls us to an unforgettable climax on the beach that is both deeply compassionate and utterly heartbreaking.